You are here

5/23/1910 - 5/13/1962

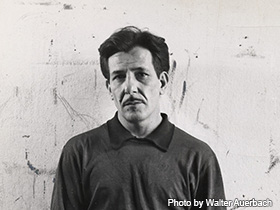

Abstract expressionist painter Franz Kline was well known for his black and white paintings.

Praised as a second generation Abstract Expressionist, Franz Kline was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania in 1910. In the late 1930's, while living in New York, Kline struggled to establish his reputation as an artist. In 1940, Kline met Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, two prominent artists of the time. Inspired by de Kooning, Kline began to enlarge his small scale black and white paintings and quickly gained notice for his large scale bold abstract works. After his death in 1962, Kline's fame quickly diminished. Since the 1980's, however, Kline's works have regained acknowledgement and appreciation.

Born on May 23, 1910 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, Franz Josef Kline grew up, according to his mother, drawing on sidewalks with the juice from the stems of rhubarb. His father, Anthony Kline, owned a local saloon and his mother, Anne Kline, was an immigrant from Cornwall, England. The second of four children, Kline was named after the Austrian Emperor Franz Josef, by his father who descended from Hamburg, Germany. In 1917, when Kline was seven years old, his father, a saloonkeeper, committed suicide. His mother remarried only a few years later and in 1919, at the age of 10, Kline was sent to Girard College in Philadelphia, an institution for "fatherless boys." Kline later referred to the institution as an "orphanage," the extended period Kline stayed at Girard, totaling eleven years, indicates that Kline may have encountered traumatic issues. Kline's mother eventually withdrew him from Girard and he was then enrolled in Lehighton High School. There he became President of the Art Club his sophomore year, the cartoonist for the school newspaper, and Captain of the Varsity football team in 1929. Due to an accident at football practice, Kline was immobilized for a period of time, during which he became increasingly interested in drawing.

From 1931 to 1935, Kline studied art at Boston University. After, Kline spent a brief period of time in New York studying at the Arts Students League, an institution for artists founded by artists. From 1937 to 1938, Kline studied art at Heatherley's School of Fine Art in England. While in London he met his wife a former British ballerina who was working as an artist's model at Heatherley, Elizabeth Vincent Parsons.

In 1938, Kline moved back to the States and situated himself in Buffalo, New York. Parsons followed him to America and they were married that same year. While in Buffalo, Kline struggled as an artist, gaining only modest acknowledgment with his small scale figurative art. To cover living expenses, Kline briefly worked as a window display designer for women's fashion, sold illustrations to magazines, and painted murals for bars. He continued to work however, determined to establish his reputation as an artist, and first presented his work at the 1939 Washington Square Outdoor Show. Kline still faced many financial troubles and he was evicted from residencies three times. Between 1938 and 1957, the Kline's moved at least 14 times. His wife also faced serious health issues, battling with depression and schizophrenia. She first entered the hospital for a period of six months in 1946, and then in 1948, she returned to the hospital for a period of 12 years. During this time, inspired by a photograph depicting the famous dancer Vaslav Nijinsky as the character of tragic puppet Petrouchka, Kline painted a series of dancers and clowns. In a later 1949 work, "Dancer at Islip," he portrayed a dancer confined behind bars. Kline visited his wife regularly, but the marriage was more or less over.

In 1940, Kline met two fellow and prominent artists, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. Kline became a regular at the Cedar Bar, also known as the Cedar Street Tavern or Cedar Tavern, a common New York City hangout for abstract expressionist artists and beat writers of the time. Pollock and de Kooning as well as Mark Rothko, and Michael Goldberg patronized the Cedar Bar, in addition to well known writers, Frank O'Hara, who later publically praised Kline's work, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Jack Kerouac, and LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka).

It was de Kooning who initially helped and inspired Kline to use a picture enlarger to enhance his art to a larger scale. Kline began by enlarging a black and white drawing of a rocking chair. He subsequently abandoned his figurative art and focused his work on "black and white" large scale abstract. The works enlarged by Kline were debuted in 1950, at the Charles Egan Gallery. This initial show in New York facilitated the establishment of Kline's reputation as a second generation abstract expressionist. Kline's abstract art, in which the importance was found in the actual painting rather than the content or source behind it, was supported by critic Clement Greenberg. In advertisement of Kline's exhibition at the Egan Gallery, Greenberg was noted in the October 29, 1950 issue of The New York Times as praising Kline as the "Most striking new painter in the last 3 years."

The cityscape of New York and natural landscape of his Wilkes-Barre roots was thought, by his audiences, to have inspired Kline's bold, black and white brushstrokes. Frequently, he named paintings after people he knew or admired, places he had lived, and even trains from his childhood. Kline's 1955 Vawdavitch was named after football player who he thought highly of. Some of his works, such as his 1952 work Painting, were given a title and subsequent paintings were given that same title followed with a number. There were also multiple untitled works in Kline's ouevre.

From 1952 to 1962, Kline spent his summers painting in Princeton, Massachusetts. His black and white abstracts were compared, with much debate, to the strokes of Japanese calligraphy, though Kline denied this interpretation explaining that he was inspired by "unconscious sources." Kline was also not interested in discussing the meaning behind his work. He emphasized that his paintings were up to the viewer to interpret without his input.

In the 1986 New York Times article, "A legacy in black and white," Kline's work is described as "anything but black and white":

If his work is boisterous, it is also silent. If it is a celebration of unfettered movement, it is also a scar. If it is filled with suggestions of windows and doors, those windows and doors have often been boarded up or slammed shut. If his paintings are abstract and irreducible, they also seem like maps charting a lifetime of journeys through rural and urban America, popular and high culture, American and European art.

In 1955, Kline slowly began to integrate color back into his paintings adding hues of brown, vivid red-orange and rust red. By 1960, he was including even brighter colors into his work. In 1961, a visit to the Johns Hopkins hospital revealed that Kline had rheumatic heart trouble. At his last show in 1961, Kline debuted his painting Andrus, named after his cardiologist, which was rich with vivid violet, red, and bright lapis blue.

On May 13, 1962, at the age of 52, Franz Kline passed away, from heart failure, in a New York hospital. After his death, the attention to his work declined along with his fame. In a 1995 Time Magazine article, Robert Hughes argues that Kline's work is not overlooked, as his works have sold for over a million dollars and his signature style remains recognizable, but that "Kline is positively obscure." Kline's name, though certainly representative of a famous artist, does seem to remain a bit neglected amongst the other artists of his time. In the 1980s, his work was once again revisited however, as the new minimalists began to study Kline's work. Consequently, Kline's work is in much higher and esteemed regard today than it was the early years following his death.

In his 2001 book, The Stamp of Impulse, Abstract expressionist prints, David Acton quotes Kline as saying, "I'm Franz, from a small town in Pennsylvania. Anything people want to know about me they can see in my paintings." Of his friend Kline, Acton wrote, "Franz was one of those people we all respected and admired."

- Palmerton, Pa, 1941, National Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C.

- Untitled, 1949, The Art Institute of Chicago

- Chief, 1950, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

- Painting, 1952, The Art Institute of Chicago

- Painting No. 7, 1952, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

- New York, N.Y., 1953, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

- Black Reflection, 1956, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- C&O, 1958, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Siskind, 1958, Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan

- Meryon, 1960, Tate Gallery, London

- Probst I, 1960, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

- Merce C, 1961, National Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C.

- "A legacy in black and white." The New York Times 19 Jan. 1986: 29.

- Acton, David. The Stamp of Impulse, Abstract Expressionist Prints. Worcester, MA: Hudson Hills Press, 2001.

- Greenberg, Clement. The Collected Essays and Criticism: Affirmations and Refusals, 1950-1956. Ed. John O'Brian. Chicago: The U of Chicago P, 1986.

- Hughes, Robert. "Energy in Black and White." Time Magazine 10 Feb. 1986: 85.

- Hughes, Robert. "The Man Who Painted Impact." Time Magazine. 23 Jan. 1995: 54-55.

- Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. "Franz Kline." 22 Oct. 2009. <>http://www.mcachicago.org/Book/Kline-txt.html>.

- Savvine, Ivan. The Art Story. "Franz Kline." 22 Oct. 2009. <>http://www.theartstory.org/artist-kline-franz.htm>.

For more information: In addition to the official Franz Kline website, http://www.franzkline.org/, an online art gallery of Kline's works may be found at Stephen Foster Fine Arts, http://www.stephenfosterfinearts.com/artists/kline/index.html

Photo Credit: Walter Auerbach. "Franz Kline." Photograph. Licensed under Fair Use. Cropped to 4x3. Source: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Source: Online Resource.