You are here

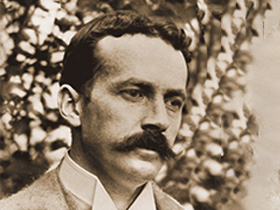

6/24/1856 - 3/9/1930

Henry Chapman Mercer was a noted archeologist and tile maker.

Born on June 24, 1856, Henry Chapman Mercer lived in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, for his entire life. He spent the first part of his life as an archaeologist, researching prehistoric life in the Delaware Valley. Mercer discovered an interest in a different type of archaeology, collecting and researching pre-Industrial Revolution artifacts, leading to his interest in tiles and ceramics. Mercer's innovative tiles and production techniques had a lasting effect on the tile industry. His tiles can still be seen in his home at Fonthill and in the Capitol Building in Harrisburg. Mercer died on March 9, 1930, at his home.

A man of many talents, interests, and accomplishments, Henry Chapman Mercer left an indelible mark on Bucks County. Born in 1856 to a wealthy family, Mercer was raised in Doylestown. His maternal family, the Chapmans, held a prominent place in local government and culture. His grandfather, Henry Chapman, was a judge and former U.S. Congressman whose varied interests influenced Mercer from childhood. His father William was retired from the Navy and became a farmer and gardener. The young Mercer attended private school, but his studies were often interrupted by travels abroad with his mother and Aunt Elizabeth. This maternal aunt, better known as "Aunt Lela," was the widow of a wealthy Italian man. Her money funded Mercer's education and travels, the travels that planted the seeds for his future endeavors.

In 1875, Mercer enrolled at Harvard University where he studied philosophy, history, and appreciation of the fine arts. He was not a distinguished student and did not graduate in the top of his class, though the lessons he learned and connections he formed in Boston were important later in life. Upon graduation, Mercer returned to Philadelphia where he studied law with an uncle and eventually took the University of Pennsylvania law examination. In 1881, his law degree was completed, but rather than join a firm, Mercer decided to go abroad.

He retraced many of the paths he had traveled with his mother and aunt in childhood, exploring even further from the south of Italy into Egypt. Throughout these trips, Mercer bought many artifacts and admired local peoples and customs. When Mercer returned to Doylestown, he became active in the Bucks County Historical Society. He had always been interested in local artifacts, and in 1882 he began to join in the search for evidence of prehistoric human life in the Delaware Valley. Archaeology was a relatively new field, and though Mercer was an amateur, he was able to join professionals, learning alongside them at the dig sites. In 1885, he published a book entitled The Lenape Stone which detailed the history of a small, engraved stone discovered in a farmer's field. The engraving depicted humans and a mastodon. Since the two were pictured on the same stone, it could possibly prove that humans inhabited the area during the prehistoric period with the mastodons. After diligent research and careful reasoning, Mercer concluded that the authenticity of the stone could not be proved. More important than the conclusion of the book was Mercer's methods and the process by which he reached his conclusions, establishing him as a scholar and an ethnologist.

From there, Mercer was invited to become a manager of the Free Museum of Science and Art in 1891 (later becoming the University of Pennsylvania Museum). During this time, Mercer learned a great deal and networked with the leading archaeologists, paleontologists, and ethnologists. In 1893, he joined the Academy of Natural Sciences, becoming curator of the Department of American and Prehistoric Archaeology. During his tenure at these museums, Mercer wrote many scholarly papers and concerned himself with the cataloging and registration of artifacts. After disputes with other executives at the museum, criticism of his work, and the loss of two mentors, Mercer left his job and his illustrious career as an archaeologist in 1897 at the age of 39.

Over the next two years Mercer shifted gears, entering a new career and a new life. Still living in Doylestown, Mercer attended a sort of "yard sale" that changed the path of his life. While searching for a pair of old-fashioned fire tongs, he came across many other old household items that he had heard of but never seen: gum-tree salt-boxes, dinner horns, rope machines. Now he turned his archaeological expertise to local, historic artifacts rather than prehistoric ones. In Henry Chapman Mercer and the Moravian Tile and Pottery Works, Cleota Reed writes, "Mercer was struck by the realization that the cast-off tools of early America represented a rich lode of archaeological evidence of pre-industrial culture." Mercer amassed a sizeable collection of pre-Industrial Revolution artifacts. In October 1897, he exhibited this collection in a room at the Bucks County Courthouse. For this occasion, the Bucks County Historical Society published a catalog of all things he had collected so far entitled Tools of the Nationmaker. At the time, his work was highly underestimated, but it set the tone for emerging thoughts on recent historic America.

While collecting more Pennsylvania artifacts, Mercer became aware of the nearly-extinct tradition of redware pottery. Once a Pennsylvania German tradition, pottery could no longer sustain most families. Under the guidance of the Herstine family of Ferndale, Mercer attempted to learn the craft. But it quickly became clear that such an art could not be learned in a few weeks or even months. After some disappointing results from the kiln, Mercer decided that plates, bowls, and cups were not the way to go. He decided he would make tiles instead, as they were easier to design two-dimensionally. For months Mercer experimented with glazes and styles, learning from some locals and teaching himself. In 1899, with the help of local professionals and friend/assistant Frank Swain, Mercer constructed the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works, which went into business in September of that year. By trial and error, Mercer improved many of his glazes and discovered that the soft Pennsylvania clay was perfect for his terracotta tiles. By 1900, Mercer tiles were highly sought-after in the Philadelphia area.

The tiles designed and produced at the Tile Works were not just any tiles. As part of the Arts and Crafts Movement, they were not solely for building, but for decorating. A counterpart of Progressivism, the Arts and Crafts Movement celebrated the human creativity and individuality in handmade artwork as a response to the Industrial Revolution, and rejecting machine-made products. His tiles were made in rich colors and unusual shapes and all handmade. The individual tiles represented people, seasons, and everyday items. Mosaics depicted scenes and told stories, often of the local Pennsylvanian way of life, Native Americans, or the discovery of the New World. Mercer also created his own production technique involving a tile press which pressed a design into the clay with a mold. Of his tile making procedures, Reed quotes Mercer as having said in 1925, "The great tile processes of the past were precluded in the United States on account of the high cost of labor. My first effort therefore was to invent new methods of producing handmade tiles, cheap enough to sell and artistic enough to rival the old ones." Mercer also developed his own, innovative methods for creating the tile mosaics and brocades for which he became famous.

Fonthill, Mercer's home, displays many of his tiles in the way he intended them to be displayed. Completed in 1912, Mercer's home still stands in Doylestown. This concrete castle remained Mercer's primary residence until his death in 1930. Since the building is made exclusively of concrete, the tiles were laid directly into the wall. A trip to Fonthill, open to the public every Monday through Saturday, will allow the visitor to see thousands of tiles in one place. One of the most amazing sights is probably the mosaics, adorning many walls and fireplaces in Mercer's home and others around the area. Another place to see Mercer's tiles is on the floor of the capitol building in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Completed in 1906, many of the floors and ceilings are adorned with mosaics depicting the history of Pennsylvania. Though this was not what the contractors had in mind, these mosaics are still admired every day by visitors to the capitol. Mercer himself described one particular mosaic as, "the equivalent of a large, Oriental rug, which if less varied in color than the carpet, is more so in its luminous interweaving of tinted shadows."

While the pottery was thriving, Mercer needed a place to keep his collections of artifacts and "tools" from Pennsylvania, North America, and abroad. The collection had grown so large (and continued to grow) that no place could hold everything. From 1913-1916, Mercer constructed another large, concrete building about a mile south of his home at Fonthill which would become the Mercer Museum. The building was specially designed to house everything he has thus far collected, with specially-designed niches and fixtures on the ceilings to hang larger items. The building stands seven stories tall and remains an architectural gem of Bucks County. Tiles.org explains that, "constructed entirely of reinforced concrete, its towers, gables and parapets announce the diversity inside." Mercer gave the building and its contents to the Bucks County Historical Society, and it remains open to the public along with Fonthill and the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works.

Mercer was a frequently sick man, his health often affecting his work. After a severe illness, Mercer died in 1930 at the age of 74. His impact lives on, not only in the field of ceramics, but also archaeology and architecture. In Doylestown, he is immortal; his buildings still stand tall, filled of the tiles, papers, books, sketches, tools, and artifacts that he created and collected.

Mercer published over 250 works ranging from letters to the editor to theses. Listed here are some of the important books he published.

- The Bible in Iron. Doylestown, PA: Bucks County Historical Society, 1914.

- Guide Book to the Tiled Pavement in the Capitol of Pennsylvania. Doylestown, PA: Bucks County Historical Society, 1910.

- The Hill Caves of the Yucatan: A Search for Evidence of Man's Antiquity in the Caverns of Central America, Being an Account of the Corwith Expedition of the Department of Archaeology and Paleontology at the University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1896.

- The Lenape Stone; or, The Indian and the Mammoth. New York: G. P. Putnam, 1885.

- The Tools of the Nationmaker: A Descriptive Catalogue of Objects in the Museum of the Historical Society of Bucks County. Doylestown, PA: Bucks County Historical Society, 1897.

- "Dr. H. C. Mercer, Historian, is Dead." New York Times 10 Mar. 1930: 16.

- "Henry Chapman Mercer." Tiles on the Web. 13 March 2008. <>www.tiles.org>.

- Reed, Cleota. Henry Chapman Mercer and the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1987.

- Reed, Cleota. "Henry Chapman Mercer." American National Biography Online. April 2001. 13 March 2008. <>http://www.anb.org>.

Photo Credit: "Portrait of Henry Mercer." c. 1900. Photograph. Licensed under Public Domain. Cropped to 4x3, Filled background. Source: Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown, PA. Source: Wikimedia.