Turn on the television. Do the names Naval Crime Investigative Service (NCIS), Crime Scene Investigation (CSI), Law and Order or True TV sound familiar? Better yet, think back to the last time the evening news was on and there were no reports of a recent crime. Whether it is on the news, The History Channel, or the number-one-rated show on television, people just can’t get enough of crime. It is everywhere. In the information age, we hear about crimes, both real and fictional, on a daily basis. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1,382,012 violent crimes occurred in 2008, and it is said that by the age of 18, the average American will have witnessed 200,000 acts of violence on television alone! Unfortunately, crime has become ingrained in our daily lives. It has become customary in American culture and no longer do murders and kidnappings come as a shock, but rather as just another unfortunate incident.

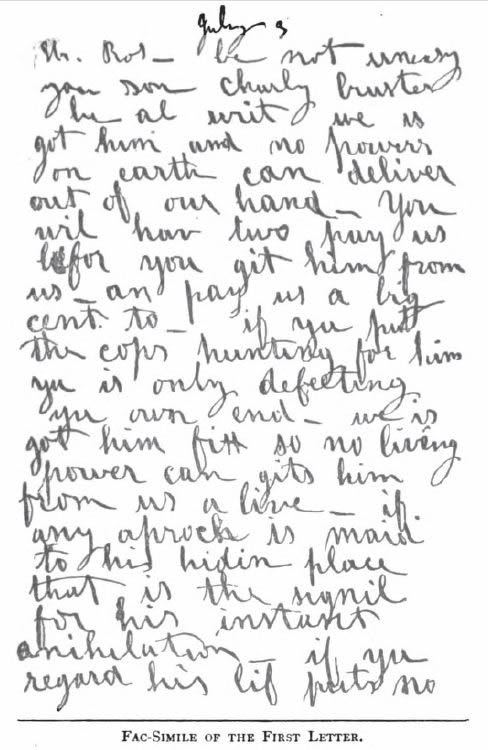

Our national obsession with crime was still young in 1874, when the Philadelphia Inquirer first described the following ransom letter: “Mr. Ros: be not uneasy you son charley bruster be all writ we got him and no powers on earth can deliver out of our hand.” Today, if a parent received this ransom letter, “proper procedures” would be set in place; police would immediately meet with the parents. Interviews and searches would be conducted almost instantly, and an Amber Alert would be sent throughout the United States. But in 1874 things were much different.

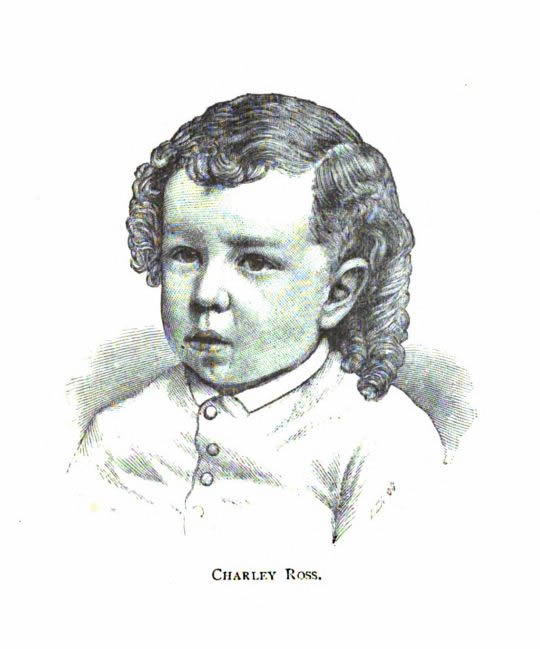

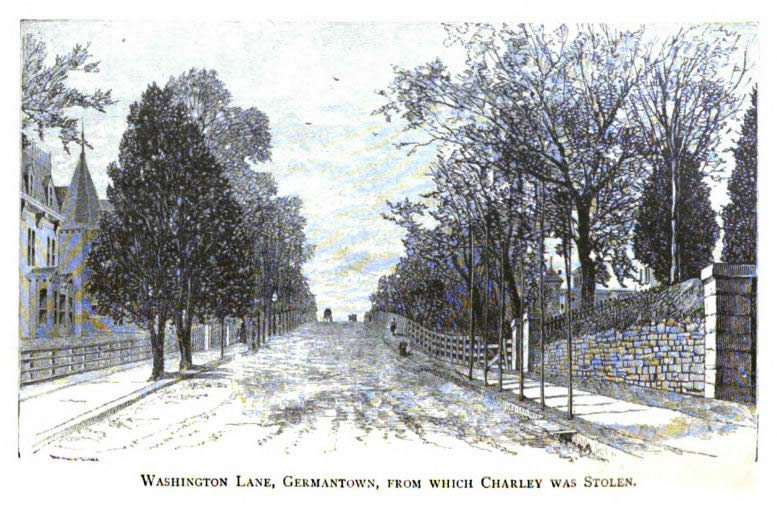

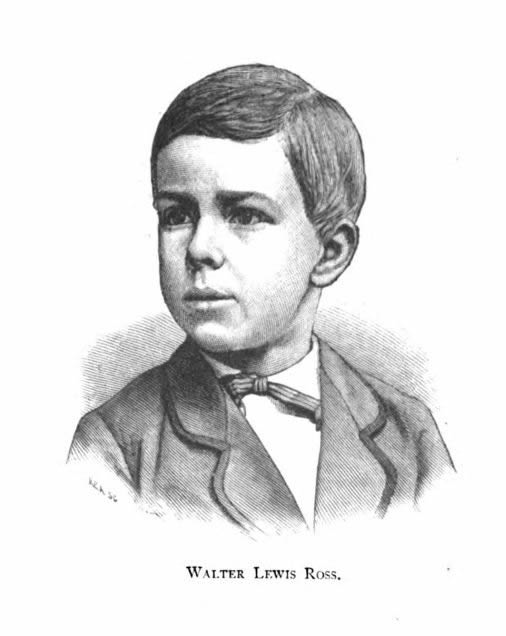

In that year, Charley Ross was a young four-year-old boy on East Washington Avenue in the Germantown area of Philadelphia. He and his brother Walter were playing outside their home when they were kidnapped by two men riding in a horse and buggy. Walter would later be set free. Charley Ross, however, became the first abduction for ransom in American history.

The two men rode past the home of the Ross children every week, offering candy and engaging the small children in conversation. It was not until July 1st however, that the men riding in that horse and buggy would by lure them to take a ride, promising them the purchase of some fire crackers for the upcoming Independence Day celebration. The eight-year-old boy, Walter, was set free just a few hours later, but Charley Ross’s fate would remain forever unknown.

The Ross family lived in a large house in a well-to-do area of Germantown, and was presumably thought to be rich by the kidnappers. But unbeknownst to them, their father Christian Ross was actually heavily in debt since the stock market crash of 1873. Although Christian Ross wished to pay the ransom, he was unable to do so and instead went to the police.

The Philadelphia Police Department, under the direction of Captain Heins would be the first to investigate the case. They began by placing advertisements in the Philadelphia Inquirer for the missing boy, stating that a $300 reward would be given for whoever could return the missing boy to his father. The advertisement also described the ransom letters the boy’s father had received.

The story of Charley “Brewster” Ross would soon become a sensation throughout the country. Police departments from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York began to help with the case, and newspapers from Philadelphia to California quickly began to publish articles on the missing boy.

An article written in the New York Herald touched upon this observation by stating, “Never within the history of the Quaker City has a circumstance arisen that so wholly monopolized its public press, or that has called to Philadelphia a greater number of correspondents from elsewhere. So great is its importance, and so direct its bearing upon the human family in general, that no particulars of the affair should be able to escape public observation, nor should any of its details be able to pass without general comment.”

As many articles similar to the one in the New York Herald were published, Americans nationwide were overcome with emotions. In The Father’s Story of Charley Ross, the Kidnapped Child by Charley’s father, Christian Ross, he describes the sorrow many felt: “Then followed varied expressions of horror, as each one realized that there existed a human being capable of committing an act so cruel, so full of unspeakable torment to its victims, as that of child stealing.”

Weeks passed with no sign of Charley’s return. Two more ransom letters had come demanding money from Mr. Ross as police departments continued their investigations. It was not until two weeks later, on July 17, that the police would get the break they were looking for. “A man named Chris Wooster, well-known to the police, was about 42 years of age, and is supposed to reside on Wood Street above, Ninth. He is a tall, thin man, with rather a bony-looking face, sallow complexion and a short, straggling beard,” was arrested. He would later be proven innocent and set free.

Not long after, two other men were suspected in the case. William Mosher, a known criminal and boat builder by trade, and Joseph Douglas, were under suspicion. Police departments searched long and hard to find the two men or any information about them, but were not successful until 23 ransom letters and five months later. The two men were caught in a burglary that ended in the death of both of them. Mosher was instantly killed, but Douglass confessed just minutes before his death that they were the men who had stolen little Charley Ross. “It’s no use lying now. Mosher and I stole Charley Ross from Germantown. God knows I tell you the truth; I don’t know where he is; Mosher knew.”

In his book, Charley’s father recounts the final minutes of Douglass’s life. “He was lying on the spot he had fallen, drenched with the descending rain, end the purposeless and miserable life of one who aided in rending the heartstrings of a family unknown to him, and in outraging the feelings of the civilized world.”

Walter, who had been set free months earlier, was brought in to confirm the dead bodies were those of the men who had taken him. After a positive identification, both Mr. Ross and the police department were overcome with sorrow that they had finally found the two men behind this heinous crime, but they could never punish them. The whereabouts of Charley Ross would forever remain unknown.

The case of Charley Ross forever changed America’s view on crime. Most Americans had never heard of such act of cruelty taken upon a child. This case was the first of its kind to ever have abductors hold a child prisoner in exchange for money. It was also the first to reach such profound importance that it went national in the news from Philadelphia to Cincinnati, New York to San Francisco. In one of the largest manhunts of the 19th century, detectives from Philadelphia and New York, the Pinkerton Agency of private detectives, and the United States Secret Service made every effort to bring the boy back to his family.

Even outside of law enforcement, there was a frantic search for Charley, which launched him into a culture icon. Thousands of posters were distributed as far as California. Christian Ross even received a telegram from circus entrepreneur P.T. Barnum that read, “If you will meet me at my home here before Monday I will pay your expenses both ways. I will pay a large reward and I think I can get Charley, if alive.”

When Christian Ross met with Barnum, he offered to advertise a $10,000 for Charley’s return in newspapers across the country. His only request was that Charley become part of his traveling exhibits. Ross agreed, given the condition that the family would reimburse Barnum, rather than having the boy join the circus.

Unfortunately, in the 1870’s, police departments did not have the technology and resources that we have today to help break cases. Those involved in the case did all they could with the resources available to them, but in the end, it would not bring Charley back. Abductions for ransom still take place, but with the help of this case, forensic scientists, and the ever-growing technology market, the United States has redefined how searches for children are now conducted. Although the ending to the story of Charley “Brewster” Ross was not what anyone hoped it would be, its publicity did have a positive and profound impact on the way such cases are handled today, and has helped in the prevention of what could have been many more kidnappings.

Sources:

- Everly, Thomas. “Searching for Charley Ross.” Pennsylvania History 67.3 (2000): 376-96.

- Fass, Paula S. “The Lost Boy The Abduction of Charley Ross.” Kidnapped: Child Abduction in America. New York: Oxford UP, 1997. 21-56.

- “Little Charley Ross: A Glimpse of Hope.” The Philadelphia Inquirer 17 July 1874: 8.

- “Media Violence.” National Center for Children Exposed to Violence. 16 Dec. 2005. 1 June 2001 <http://www.nccev.org/violence/media.html>.

- Ross, Christian K. The Father’s Story of Charley Ross: The Kidnapped Child. Philadelphia: John E. Potter & Company, 1876.

- “The Stolen Boy Developments in the Case of Little Charlie Ross.” New York Herald 20 July 1874: 10.

- “2008 Crime in the U.S. Released.” Federal Bureau of Investigation. 14 Sept. 2009. 1 June 2011 <http://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2009/september/crimestats_091409>.