Drivers have had the pleasure of traveling along scenic route 322 as they cruise across the state, but before 1846, the towering mountains, expansive river, and impervious woodland located in the Appalachian Thruway remained unobserved by the majority of citizens. This all changed in the 1890s, when photographer William Rau was commissioned to capture Pennsylvania’s beauty. His conveyance for the undertaking was the flourishing Pennsylvania Railroad. Traveling the rail lines that extended from Philadelphia to St. Louis, Rau immortalized the 19th century glory of Pennsylvania’s natural landscape while advertising state-of-the-art transportation provided by the new line.

Rau’s promotion of the “Pennsy” helped the railroad to become one of the most recognized and revered corporations in the world for almost 100 years. Whether the public boarded its passenger cars for leisure travel, toiled on its tracks on blistering summer days, or generated wealth from its publicly traded stock, the PRR touched the lives of over half the nation’s population from its incorporation in 1846 until its bankruptcy in 1970.

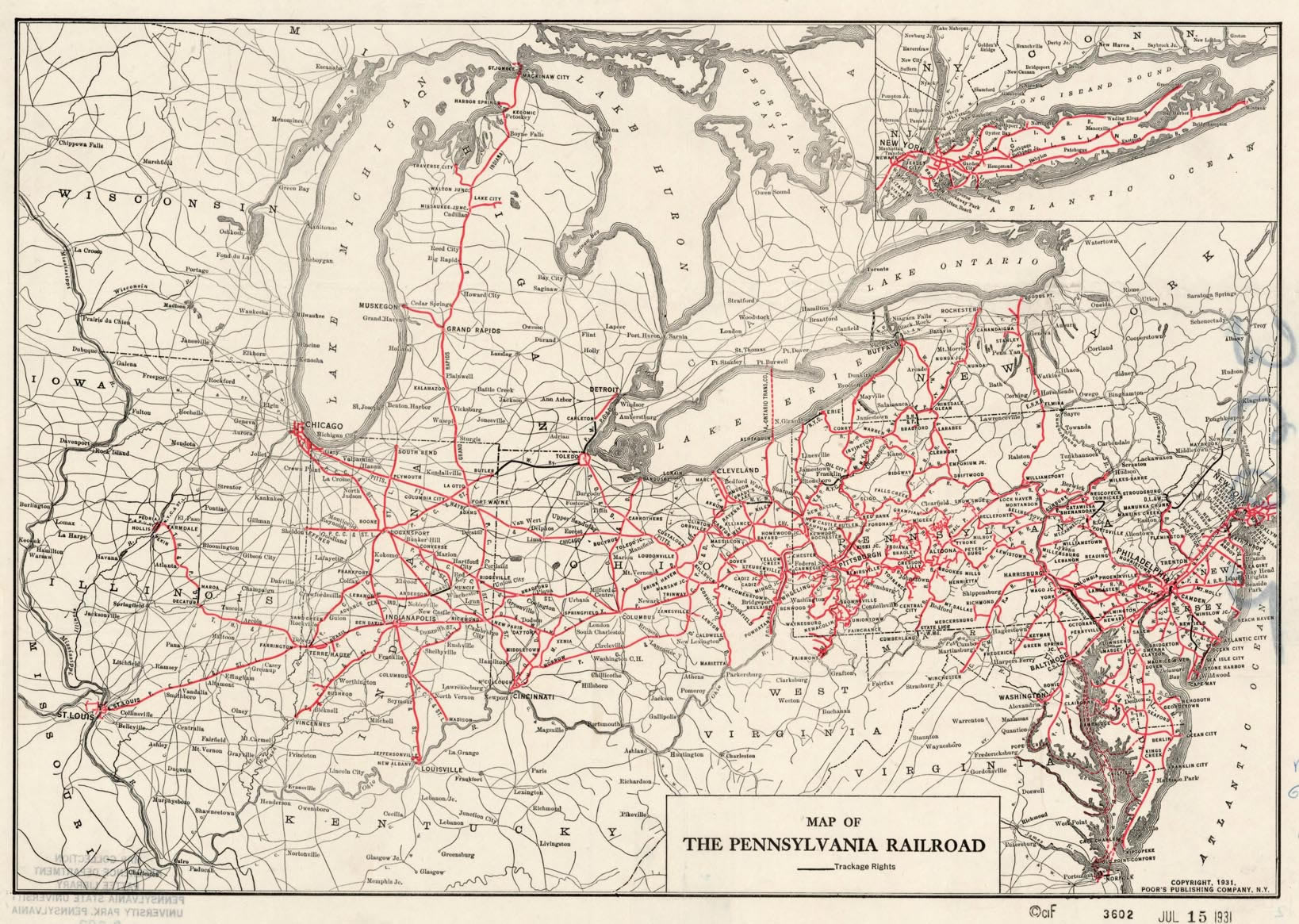

At the height of its power, the Pennsylvania Railroad was a giant both as a measure of track mileage and corporate power. In the early 1900s, the PRR was reputedly the largest publicly-owned business in America. As both a passenger- and freight-carrier, it grew from a single track into a web that spanned from the East Coast as far as Illinois and the tip of Michigan. Each rail set down in the Pennsy’s expansion was paralleled by a transportation or organization precedent.

Prior to the existence of the Railroad, Pennsylvania’s commerce was plagued by inefficiency. Disjointed rivers, roads, and canals were inadequate in linking centers of trade such as Philadelphia and Pittsburgh with the “interior,” isolated regions just west of the state. Pennsylvania was finally spurred to action in 1846, and perhaps the surrounding states of New York and Maryland deserve credit. The two states brought about a commerce race in which they ushered trade further and further west. New York gained advantage through its Erie Canal, while Maryland built the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. It was Maryland’s scheme to connect the cities of Baltimore and Pittsburgh that triggered Pennsylvania to develop its own plans.

The Pennsylvania Railroad was incorporated as a line that would link Harrisburg to Pittsburgh. It grew from an already existing railroad, the Philadelphia & Columbine. By 1852, the PRR had completed its initial track, and over the next five years it extended east of Harrisburg to Philadelphia. The state-wide, all-rail route conquered the barrier imposed by the Alleghenies and caught Pennsylvania up in the trade race. With an unparalleled zeal and a pace that would characterize all of its developments, the Pennsy expanded its reach until, in 1873, it had become a powerhouse. Spanning more than 6,000 miles, it reached all the way to Chicago and St. Louis.

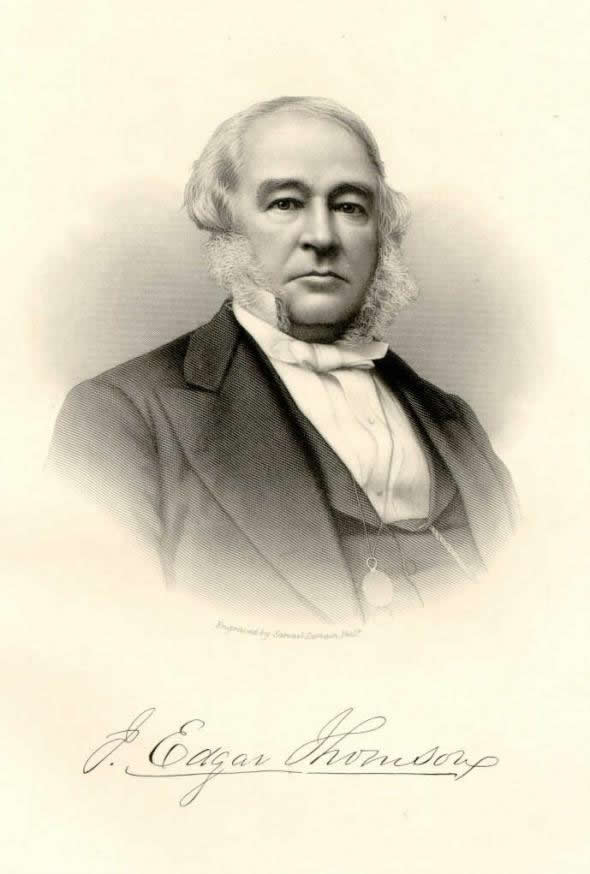

What motivation was required to lure the best engineering talent to the Pennsylvania in its fledgling days? A $5,000 salary persuaded J. Edgar Thomson, the determined, dynamic individual who led the PRR’s unequaled early expansion. He was hired as the first chief engineer and became president of the corporation in 1852. Thomson had the ability to develop engineering solutions to business problems, and as a result his innovations were not only applied to current issues but were incorporated into future applications as well. One such advancement was an idea for traffic control. He created separated tracks for freight trains, freeing the main lines for passenger travel. Thomson’s idea later led to the creation of Low Grade lines, which allowed freight trains to bypass areas of steep slope. Thomson’s progressive plans were integrated into the values of the PRR as an organization, and set the bar for continuous improvement and innovation. Historian Don Ball remarks, “the original charter was from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh, and while that segment was under construction, Thomson was thinking of other ways of getting far beyond Pittsburgh.”

Under Thomson, the Pennsy achieved unrivaled engineering feats. His direct designs produced the Horseshoe Curve in Blair County, a segment of track some consider the greatest section of the Railroad. The 220-degree curve built in 1854 loops around Kittanning Gap and allows trains to overcome the steepness of the Alleghenies, rising one foot every one hundred feet. It also saves trains from crossing the water at the base of Kittanning Gap. This railroading gem would act as a magnet for the town of Altoona, which hosted the greatest concentration of railroad shops by 1925. Thomson’s accomplishments gathered a momentum that would carry on until the 1940s. Common were articles extolling the velocity and precision of the PRR; one New York Times article from 1897 detailed the replacement of a 242-foot long iron bridge in Philadelphia in less than three minutes.

A later president, Alexander Cassatt, continued the tradition of building the biggest and best, and concentrated his efforts around Harrisburg. In 1902, he commissioned the Rockville Bridge in Dauphin County, at the time the longest stone-and-concrete arch bridge in the world. Still used today, it spans 3,820 feet over the Susquehanna River, but has not sacrificed any strength for breadth. The bridge was recognized as a historic landmark when in 1972 it survived Hurricane Agnes’ destruction. Just down the river in East Pennsboro Township, Cassatt constructed another “largest” in 1906. Enola Yard could hold the most cars of any freight classification yard, and, until the 1950s, sometimes more than the twelve thousand car limit passed through it each day.

With industry booming at the turn of the 20th Century, the Pennsy was having difficulties handling the increasing traffic that came with untamed growth. Thomson had previously pioneered the switch from wood to coal to run his steam-powered locomotives, but it became evident that an entirely new type of locomotive was needed. Executives opened up to the possibility of electrification. In 1909, after completing an electrified tunnel under the Hudson River to Manhattan, lines of alternating current were extended deeper into Pennsylvania. By 1938, it became the most electrified railroad in the world when it lit up its branches from New York to Harrisburg.

Electrification eliminated the smoky inefficiencies of the railroad, but it still met opposition from some organizations. The National Coal Association was enraged at the loss of its most valuable client; the PRR had once hauled ten percent of the nation’s coal. For the Pennsy, though, the decision to electrify its lines generated unprecedented power. Operating expenses dropped by $7.7 million dollars while revenues increased, and shortened travel time looked more appealing to passengers than ever.

Electrification brought about a new generation of locomotive. Once the fastest and most efficient trains, steam-powered engines were soon dethroned by electric ones. From 1934 to 1943, Altoona’s railroad shops turned out the famous GG1 fleet. The locomotive with the sleek, streamlined style was designed by Raymond Loewy and could travel up to 100 mph, speeds never experienced before. These trains were granted the privileged assignment of passenger transportation, while the outdated steam engines were loaded with freight.

The rate alone at which the Pennsy achieved electrification was unheard of; but even more amazingly, it did so in the worst of economic environments. While the Great Depression in 1930 left the PRR searching for electrification funds, aid from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and some private sources boosted the project while most of Corporate America failed. It was also during these times that a second growth-accommodation project was completed. In Philadelphia, trains carrying 300,000 commuters were backing in and out of the dead-end Broad Street Station daily; the corporation opted to replace it with a larger “Pennsylvania Station.” Capital was scant, but the architecture firm Graham, Anderson, Probst and White miraculously created a $52 million dollar classical revival structure. The 95 foot-high ceilinged, 210,000 square foot 30th Street Station was opened in 1933 and today is the largest existing and second most active railway station in the world.

For over a century, the Pennsylvania Railroad powered its way through trials and tribulations. It helped shape military strategy during the Civil War, and survived the First World War. It made its greatest improvements while the American economy plummeted in the ‘30s. The decline of the great Pennsy did not occur with WWII, but in the era following. Faster, more convenient commercial airplanes and motor vehicles that developed during the war siphoned away the railroad’s passengers. In 1968, the Pennsy made a final attempt to save itself by merging with New York Central to form Penn Central, but was unable to recover. It filed for bankruptcy in 1970 and was bought by Conrail and Amtrak.

Those who lived during its prime remember the Pennsylvania not as the dilapidated company forced to remit its title, but as “The Standard Railroad of the World.” During its lifetime, the Pennsy’s web of rails stretched wide, but did not weaken. A Fortune magazine writer once wrote, “Do not think of the Pennsylvania Railroad as a business enterprise. Think of it as a nation.” It certainly could be called a “nation” in reference to the number of people it involved; in the early 1900s it employed over 280,000 citizens. More significantly, however, the Pennsy cultivated an identity for itself equal to the culture instilled in a country. The Pennsylvania took great pride in itself as a corporation, and set a high standard for others to follow.

Al Giannantonio, Philadelphia chapter president of the railroad’s historical preservation society, explains his passion for the old corporation, noting, “I worked as a fireman for one summer on the PRR and never forgot it.” Even when the Pennsy’s contact with citizens such as Mr. Giannantonio was minimal, it exuded a lasting influence upon them. President Cassatt began standardization of the Pennsy in 1867. While other companies scrambled through scrap yards to obtain loose train parts, the PRR produced a blueprint from which emerged a uniform fleet. Easily recognizable were the “Brunswick Green” locomotives pulling their “Tuscan Red” passenger cars adorned with gold leaf. Its pioneering vestibules were revered as they led the switch from wood- to steel-bodied cars and sacrificed no bit of grandeur for greater passenger capacity. Despite hardships, the company continued to pay dividends to shareholders throughout its lifetime. The PRR was truly impressive and influential; not just as a railroad company, but as a representative of American corporations.

Hold up a photograph by William Rau today, and one can see that the tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad exist much as they did more than a century ago. The splendor of the accommodating passenger cars pulled by steam engines has long been replaced by more economical diesel locomotives, but the PRR leaves a legacy even more permanent than its rails and crossties. On the first days of the Pennsy, the conductor would call, with more implication than he intended, “All Aboard!,” and soon willing passengers would be traveling forward, looking out the window at a blurring scenery and passage into the future.

Sources:

- “A FEAT OF ENGINEERING.; Pennsylvania Railroad Replaces an Old Bridge Span with a New One in Than Three Minutes.” The New York Times 18 Oct. 1897: 5.

- Ball, Don. The Pennsylvania Railroad, 1940s-1950s. 2nd ed. Chester, VT: Elm Tree Books, 1986. 10-30.

- Burgess, George H., and Miles C. Kennedy. Centennial history of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, 1846-1946. New York: Arno Press, 1949. 700-50.

- Kennedy, Joseph S. “Society keeps ‘Pennsy’ fans on track Train buffs memorialize the Pennsylvania Railroad’s illustrious past.” Philadelphia Inquirer 13 July 2003, n-montco ed.: L8.

- Middleton, William D. The Pennsylvania Railroad Under Wire. Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Books, 2002. 6-20.

- Plant, Jeremy F. Trackside under Pennsy wires with James P. Shuman. Scotch Plains, NJ: Morning Sun Books, 2000. 1-50.

- “The Railroad in Pennsylvania.” Explore PA History. 2003. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. 1 Apr. 2009 <http://explorepahistory.com/story.php?storyId=19>.

- Treese, Lorett. Railroads of the Pennsylvania: Fragments of the Past in the Keystone Landscape. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. 76-78.

- Van Horne, John C., and Eileen E. Drelick, eds. Traveling the Pennsylvania Railroad: The Photographs of William H. Rau. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001. 138.