Crow’s feet, frown lines, and sagging are all tell-tale signs of aging. From birth, the media emphasizes the value of beauty. Supermodels get Botox injections to smooth out wrinkles, and less affluent individuals rely on the creams found in cosmetic aisles or behind pharmacy counters. Despite the advertising efforts of the cosmetics industry, few products deliver on their promise to erase the signs of aging, except one. Retin-A, a skin cream developed in 1967 by Dr. Albert Kligman, was initially used to treat acne but would later be discovered as a solution to wrinkles and aging.

“A fascinating person, with two speeds – bloody genius or wrong.” - Dr. Fred Urbach, former dermatology department chair of Temple University on Dr. Albert Kligman

The man behind Retin-A, Dr. Albert Kligman, began his education at the Pennsylvania State University, earning his bachelor’s degree in botany in 1939. Kligman then attended the University of Pennsylvania, receiving his doctorate in botany with a focus on fungi in 1942. During World War II, the U.S. government asked Kligman to travel to South America in order to find plants that could cure insect-borne diseases such as malaria. Unfortunately the government cancelled the trip, possibly due to Kligman’s affiliations with the Communist Party. Without any other plans, Kligman decided his only choice was medical school, enrolling at the University of Pennsylvania. Kligman chose to specialize in dermatology since he mistakenly assumed that the field of dermatology would deal with fungal infections, however he quickly found that fungi only play a small role in skin diseases. After earning his M.D. in 1947, Kligman began to work at the University of Pennsylvania hospital and taught dermatology at the medical school. Dr. Kligman studied skin ailments such as dandruff and athlete’s foot during this time, and his highly regarded status as a researcher allowed him access to test subjects at both the University of Pennsylvania and at the nearby Holmesburg Prison, located in Philadelphia.

“Rules don’t apply to geniuses.” Dr. Albert Kligman

During the 1950s and 1960s, prison inmates were commonly used for the preliminary testing of experimental drugs, and Holmesburg Prison was no exception. Prisoners were paid to participate in studies that involved radioactive isotopes, dioxin (a known carcinogen that leads to birth defects and skin diseases), and other gruesome experiments. Dr. Kligman was initially invited to Holmesburg Prison to help treat an outbreak of athlete’s foot, but quickly saw the potential of the prison as a limitless supply of test subjects on which he could experiment without consequence. The U.S. Army financed his early experiments at Holmesburg , which tested the hardening process of the skin. In these tests, Kligman applied strong acids and other irritants to the skin in order to observe the results. While some hardening of the skin was achieved, many of the substances used were so toxic that intense blistering resulted. After three years researching skin hardness, Kligman turned his studies to acidic Vitamin A, known as tretinoin or retinoic acid. Previous studies in Europe showed that retinoic acid greatly damaged the skin, however these results did not diminish Kligman’s interest in this acid.

“All I saw before me was acres of skin. It was like a farmer seeing a fertile field for the first time.” Dr. Albert Kligman on his first visit to Holmesburg Prison

Initially Kligman studied retinoic acid’s effect on treating keratonic disorders, which are characterized by a thick, scaly outer layer of skin. After observing that retinoic acid cured keratonic disorders by removing the top layer of skin, Kligman theorized that retinoic acid could possibly combat acne. He hypothesized that retinoic acid would slow down the production of dead skin cells, preventing acne. Kligman tested retinoic acid on patients at the University of Pennsylvania’s Acne Clinic and inmates at Holmesburg (some of which had chemically induced patches of acne) by applying retinoic acid to one half of the face and another experimental drug to the other, and monitoring the patches of acne on the subject’s face. These studies showed that retinoic acid could be used to reduce acne, leading to its approval by the FDA in 1971 and was subsequently marketed under the brand name Retin-A.

“I have always told my students that if you start to believe your patients, you’re gonna end up a quack.” Dr. Albert Kligman

Doctors commonly prescribed Retin-A to adolescents, however older women were also given Retin-A to treat their acne. After using this drug, the women reported to their doctors that using Retin-A seemed to reduce their wrinkles, firm their skin, and make their skin look ‘rosier.’ After repeatedly hearing these claims, Dr. Kligman decided to investigate if Retin-A could reduce the appearance of wrinkles. Kligman tested Retin-A on rhino mice (shown above) and on humans to determine the validity of these claims. Rhino mice are fully covered in wrinkles, and when treated with Retin-A twice a day for six weeks, the mice were practically wrinkle-free and appeared as smooth as normal hairless mice. In 1986, Dr. Kligman and associates from Philadelphia’s Skin Study Clinic tested Retin-A on 400 older female women. The results of these tests showed that Retin-A improved skin quality by improving blood flow and reducing wrinkles. Along with Dr. Kligman’s test results, the American Academy of Dermatology reported that “women of ages 58 to 71 who applied the cream nightly displayed better color, texture and smoothness than women who used a standard beauty product. Retin-A was also found to erase some blemishes and fine wrinkles – and the changes were noticeable, but lasting.” 1 The Harvard Medical School Health Letter of December 1987 also stated that “..persuasive clinical data indicate that [Retin-A] actually does improve the quality of skin. The results suggest that after four to six months’ treatment there are subtle but real changes in skin including less wrinkling.”1 After determining that Retin-A could reduce the appearance of wrinkles, the cream was repackaged under the name Renova. While tests have proven that Retin-A does reduce wrinkles, the question remains of how Retin-A works to improve skin and wrinkles?

“Ninety percent of what the laymen think of skin aging isn’t the result of age.“ Dr. Albert Kligman

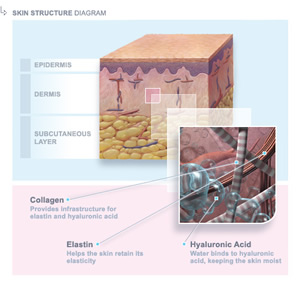

While aging leaves skin weaker, the major cause of wrinkles, spots, and sagging is the sun, in a process called photoaging. Skin is made up of three layers (shown left), and normally the top layer, called the epidermis is made up of orderly rows of skin cells, similar to a brick wall. With exposure to sun, this wall of cells becomes disorganized, resembling a crumbling wall. The cells can no longer reproduce in an orderly fashion, leaving the skin wrinkled. Sun damage also causes two proteins found in skin, collagen and elastin to be produced in smaller amounts. Collagen and elastin cause the skin to act like a rubber band; elastin allowing the skin to snap back to its initial form after being stretched and collagen preventing the skin from tearing when stretched. Without these two important components, skin is left to sag and wrinkle. Fortunately, Retin-A can reverse the negative effects of photoaging. Rosier skin is achieved when using Retin-A because the cream increases the flow of blood in the skin. Retin-A also thickens and reorganizes the top layer of skin, and restores cell size to normal, which increases the production of collagen and elastin, all of which reduces fine wrinkles.

“The Retin-A side always gets worse before it gets better.” Dr. Chalmers Cornelius, worked with Dr. Kligman during acne experiments

Unfortunately the seemingly simple reversal of aging using Retin-A is not without a cost. Using the cream often results in irritation and redness due to the peeling away of the top layer of skin. Another downside is that the skin may burn when first applied. Since skin can become tender when first applied, the initial dosage is usually only 2 or 3 times a week, and the redness fades in a few days after usage of Retin-A is stopped. Along with the cosmetic irritation caused by Retin-A, the cream must be used indefinitely to continue seeing the anti-aging results.

While everyone ages, an emphasis is put on looking young for the longest time possible. Plastic surgery, injections, and overpriced creams are all options for slowing the signs of aging, but a simpler solution lies in Retin-A. While the main reason many choose to use Retin-A is purely for cosmetic reasons, many other benefits result from using this cream, such as the reversal of skin damage. Despite being discovered over forty years ago, Retin-A is still a relevant treatment for wrinkles, and without the work of Dr. Kligman, the world would look a bit wrinkled.

Sources:

- Bark, Joseph P. “Retin-A and Other Youth Miracles: A Dermatologist’s Guide to Looking 10 Years Younger.” Rocklin, CA: Prima Publishing & Communications, 1989.

- Gellene, Denise. “Dr. Albert M. Kligman, Dermatologist, Dies at 93.” New York Times 23 Feb. 2010: 25.

- Hornblum, Allen M. Acres of Skin: Human Experiments at Holmesburg Prison : a Story of Abuse and Exploitation in the Name of Medical Science. New York: Routledge, 1998.

- Kiester, Edwin Jr. “Science Takes the Wrinkles Out of Aging.” 50 Plus 1 Feb. 1988: 22.

- Kligman L. H., Kligman A. M. “The Effect on Rhino Mouse Skin of Agents Which Influence Keratinization and Exfoliation.” Journal of Investigative Dermatology (1979) 73: 354–358.

- “Matters of Scale – Spending Priorities.” World Watch Magazine Jan/Feb 1999, Volume 12, No. 1. 24 May 2010 <http://www.worldwatch.org/node/764>.