Emergency sirens wailed as turbid water surged through the streets doing little to quench the fires that roared above its surface. Hurricane Agnes had arrived to greet unsuspecting residents, and she would prove to be an unruly, unwelcomed guest. Just a few days prior to June 23, 1972, meteorologists spoke of the potential for light rain, a by-product of a distant tropical storm, to wash over north-central Pennsylvania. Little did they know the light rain would turn into flash-floods and, ultimately, into the costliest and most devastating natural disaster in the history of the Commonwealth.

The makings of the hurricane, or “Tropical Storm Agnes,” were nothing more than a strong wind. Topping 85 mph and just grazing over the Caribbean, it started to make its way up the Eastern seaboard. After it intensified in power, Hurricane Agnes staked its claim as the first hurricane of the season when it hit the Florida Panhandle. While it caused some minor damage during its travels through Georgia and the Carolinas, the hurricane seemed non-threatening to those in its path. After a brief exit into the Atlantic, the storm re-emerged in time to hit southeastern New York with heavy rainfall. Quickly, officials began to question the hurricane’s quiet demeanor; their suspicions warranted the issuance of a flash-flood warning for the areas along the both the west branch and east branch of the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. According to the National Climate Data Center, the cities of Wilkes-Barre and Harrisburg were among the most devastated areas in the state.

The Susquehanna River’s susceptibility to flooding, particularly near Plymouth, prompted the United States Army Corps of Engineers to construct a dike system in the 1940s to prevent major destruction of the Wyoming Valley. Along with the dike system, banks were lined with 13-15 foot levees. This precaution would have been a sufficient defense if water levels were to reach those seen in the ravaging flood of 1936, a disaster some of the elderly residents in the area still spoke of. However, it was evident that the heavy rain that would drench that region of Pennsylvania this time around would cause the river to swell substantially; the levels would quickly surpass the 35-foot limit of the barriers that protected near-by farms and town as the storm had bombarded the area with rain for close to a week.

On June 22, the murky waters of the Susquehanna reached eight feet above normal river levels. Fourteen hundred National Guardsmen were ordered to the area where they employed efforts to secure low-lying areas by erecting walls of shale, sandbags, and rock. Town officials issued evacuation notices and urged the 72,000 members of surrounding communities to leave their homes immediately. Either out of stubbornness or good faith, some residents refused to budge and decided to wait out the storm. Perhaps it was a misconception regarding the severity of the circumstances that had lead some residents to make the decision to stay. Not sensing the urgency, most believed Hurricane Agnes’ onset meant little more than light flooding in their basements. Regardless of their reasoning, some families simply refused to leave their homes unprotected, whether from the flooding that was about to ensue or potential looters. In preparation, families hoarded food supplies, relocated furniture and valuable possessions to higher levels in their homes, and made somewhat futile attempts to prevent water damage by lining doorways with rolled up rugs, newspapers, and even toilet paper.

By Friday, June 23, the river swelled to 38.5 feet; the dike had long since buckled and left surrounding towns truly vulnerable. By Saturday evening, the water levels had reached their peak. In the end, Hurricane Agnes pummeled Wilkes-Barre and the Wyoming Valley with 14 trillion gallons of water; submerging homes and destroying communities. The storm completely destroyed 3,500 homes while damaging 64,000 houses in Pennsylvania; 13,000 of those homes were located in Wilkes-Barre. In Kingston, only 30 of the 6,600 homes that comprised the town were left unscathed by the implacable fury of Hurricane Agnes.

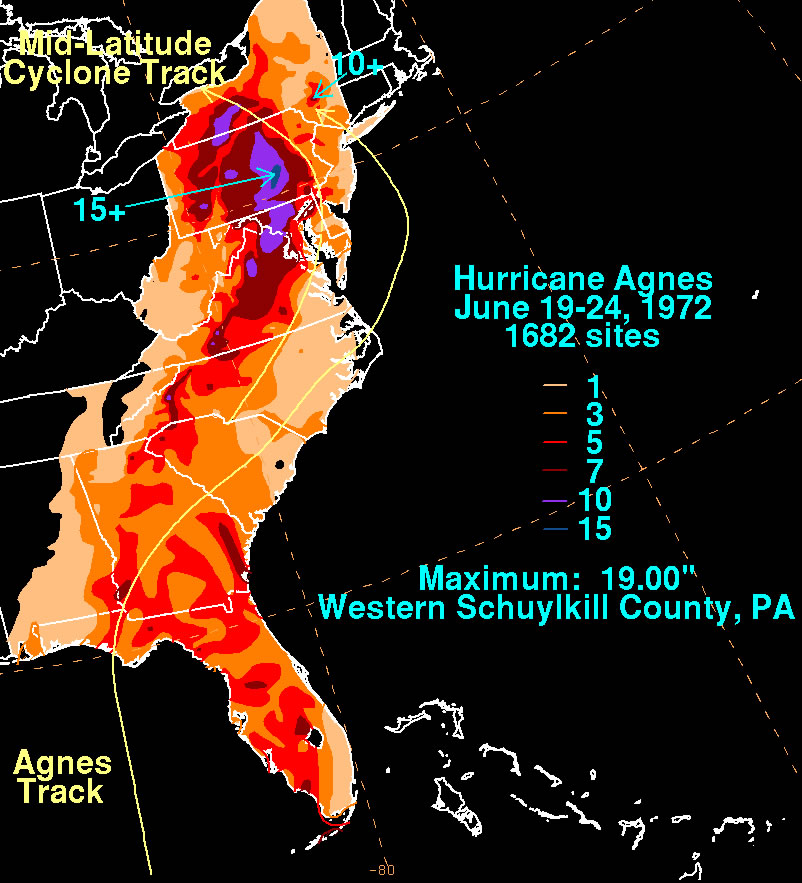

Agnes’ mood was mercurial and unpredictable; some areas where simply doused with rain while others, like Philadelphia, were merely misted in comparison, receiving just a few inches. After devastating north central Pennsylvania, Agnes veered southwest towards Harrisburg. On June 24, Pittsburgh’s water levels crested at 38.5 feet. President Richard Nixon was forced to declare Pennsylvania, along with Florida, Virginia, Maryland, and New York, disaster areas which made the states eligible for national relief. In the next coming days, the National Guard and the Red Cross, along with volunteers from the community, arrived on the scene to respond to the desperate calls for help from stranded residents.

The main stem of the Susquehanna Basin took the brunt of the storm. It was estimated that Shamokin, Northumberland County, was saturated with 18 inches of rain while Schuylkill County, located in the Mahantango Creek Basin, was deluged with 14.8 inches of rain in a 24-hour time period. The torrential downpour, combined with the 2-3 inches that battered the state in the week prior to June 23, resulted in truly fortuitous water levels in some parts. The storm reached its full intensity when it converged with an extratropical cyclone circulation over western Pennsylvania. Agnes, a Category 1 hurricane for only an estimated 36 hours, did not hit with brutal force. Instead, its notoriety stems from its noteworthy scope; Hurricane Agnes had a diameter of 1,000 miles. Pennsylvania’s uneven terrain, already strained reservoirs, and simultaneous weather happenings became integral ingredients in this recipe for disaster.

The unwavering relentlessness of Hurricane Agnes took a daunting toll; it tore through Pennsylvania, decimating phone lines, cutting off electricity, and concealing the beloved landmarks of communities. Bridges collapsed under pressure, dams were overwhelmed, and sections of road floated off into the distance. In some areas, the sheer force of tidal waves spawned by the hurricane ripped houses from their foundations. Public squares and shopping centers were blanketed with rushing water. Streets were converted to canals, as lakes seemed to sprout overnight throughout the region; tops of obscured structures and defeated streetlights and street signs poked through the surface of the water. Fires, unreachable by firefighters, crackled atop buildings. The drone of rescue helicopters cutting through the sky overhead broke the eerie hum of churning water that echoed through every neighborhood.

The lack of communication, in conjunction with a loss of electricity and heat, posed a serious dilemma for all, but particularly medical and long-term care facilities. Protecting the most vulnerable populations, the elderly along with the sick, became of the utmost priority. The Luzerne County Bureau for the Aging, left with the arduous task of relocating the elderly, estimates that they were able to aid 3,000 seniors aged 55 and above in the month following the storm. However, the mission was heart-wrenching for those who watched as the elderly struggled to leave their homes, part with their belongings and loved ones, and cope with their immense losses.

Sharon Miers, a bureau case worker involved in relief efforts at the time of the flooding, confided to a Times Leader reporter that “there was a lot of crying, a lot of patting on the shoulder. That came first. Then we tried to answer their needs.”

John Robinson, 55, remembers helping clean up the soaking books at his flooded church in Harrisburg. He had drawn a line in white crayon on the church’s red brick to denote the five-foot-high watermark that is still there today. “It’s really something that no one should have to go through, but lots of people did,” Robinson said.

Even as the river swelled and overwhelmed the landscape with scattered debris, the spirit of communities in devastated areas remained intact. Families opened their doors and offered their homes to less fortunate neighbors. Those who were strong enough to brave the danger volunteered to cruise the streets in small rowboats to look for those who were stranded and in need of higher ground. High schools, local college campuses, and churches became makeshift havens. Shelters, staffed by the good-hearted individuals of the Red Cross and Salvation Army, housed thousands of evacuees and provided food, beds, safety and most importantly, hope.

On June 23, 1972, Harrisburg’s Patriot-News was canceled for the first time since it began in 1852. Nearly a quarter million dollars’ worth of newsprint stored in the Patriot-News building was destroyed, which was the newspaper’s 30 day supply. Additional office equipment, including typewriters and adding machines, were also destroyed. It was not until June 28 that the newspaper was up and running for their evening edition, which was a special flood edition focusing on the clean-up and rescue work that was still going on.

Hurricane Agnes finally said good-bye to Pennsylvania on June 25 with its sights set on western New York. Agnes left quite a legacy among those who suffered her wrath; as a result, the name became the first of five Category 1 hurricane names to be retired and barred from future use. Homes and public utility plants were inundated, crops destroyed, and lives were interrupted all in a matter of a few days. Across the state, 48 individuals lost their lives. Consequently, flooding resulted in a record-shattering $2,119,269,000 in damage and left 220,000 homeless.

In some areas, recovery, both physical and mental, took months. Electricity did not reach a good number of houses for 104 days after the flooding. Residents whose homes withstood the brutal waves were left with little consolation as almost all their belongings were water-damaged and caked with a thick layer of yellow mud. Soaked insulated walls and ceilings fell through, unable to withstand the weight of the water. Heaps of discarded furniture lined the streets as some in the subsequent weeks as some were forced to gut their beloved homes.

Edmund Poggi, Jr., of Kingston recounted the events of that week and reflected upon his drowned home for the Times-Leader. “I looked at the house and turned away. The water had risen six feet on the first floor. Everything was slimy, dirty, and chaotic. We broke our backs working to save everything.” He continued, “But the hardest things to lose were our books and pictures, the family memorabilia.”

As the water subsided, survivors took small steps to rebuild structures, a sense of community and their lives. Buildings and homes of devastated areas re-emerged from beneath the water and life began to return to normal. Today, towns have long since recovered from Hurricane Agnes’ visit; businesses have restocked their shelves, families have furnished their homes with new fittings and streets have come alive with the allure of new attractions since that faithful week almost four decades ago. Neighborhoods have been able to dust off the yellow mud to expose even better versions of themselves. The memories, however, remain lucid in the minds of those who managed to shake the grip of Hurricane Agnes and survive. While not many speak of the storm, signs, standing tall and bearing its name, tell its story and provide many with a true sense of its magnitude even today.

Sources:

- “Hurricane Agnes still ranks as Pa.’s worst disaster.” USATODAY. Web. 28 Feb. 2010. <http://www.usatoday.com/weather/hurricane/2002/6-20-agnes-revisited.htm#....

- Ivory, Karen. Pennsylvania Disasters: True Stories of Tragedy and Survival. Guilford, CT: Morris Book Publishing, 2007. 119-23.

- “Middle Atlantic River Forecast Center - Hurricane Agnes.” National Weather Service Eastern Region Headquarters. 28 Jan. 2006. 28 Feb. 2010. <http://www.erh.noaa.gov/er/marfc/Flood/agnes.html>.

- Mooney, Tom, and Dawn Shurmaitis. “The Day That Changed Our Lives.” Times Leader [Wilkes-Barre] 1992, Special Edition ed.: 2-36.

- “NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE MARKS 25TH ANNIVERSARY OF HURRICANE AGNES.” NOAA Public, Constituent and Intergovernmental Affairs - HOME. 11 June 1997. Web. 28 Feb. 2010. <http://www.publicaffairs.noaa.gov/pr97/jun97/noaa97-r228.html>.

- “NCDC: Climate-Watch, June 2002.” NCDC: * National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) *. June 2002. 28 Feb. 2010. <http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/extremes/2002/june/extremes0602.html>.

- “Patriot-News Co. Cancels Edition for First Time.” The Patriot and the Evening News [Harrisburg] 28 June 1973: 2.

- “U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Pittsburgh District - Hurricane Agnes - 1972.” Pittsburgh District - US Army Corps of Engineers. 27 Feb. 2006. 28 Feb. 2010. <http://www.lrp.usace.army.mil/pao/h-agnes.htm>.

- “USATODAY.com.” News, Travel, Weather, Entertainment, Sports, Technology, U.S. & World - USATODAY.com. 2008. 28 Feb. 2010. <http://www.usatoday.com/weather/whagnes.htm>.