Think about a grilled cheese sandwich without the slice of melted American cheese. The luscious, oozing cheese spread evenly and smoothly between slices of bread for most is a treasured childhood memory. Without that sliced cheese a key element of flavor and texture would be missing.

Like many other great findings, cheese was discovered by accident. Cheese lore has it that an Arabian discovered cheese as he was traveling through a desert. He had brought milk along on his journey. The milk was stored in a sheep’s stomach lining, and as he traveled, the intense sun activated the enzymes in the lining turning the milk into liquid whey and solid curd; thus, the first cheese was revealed.

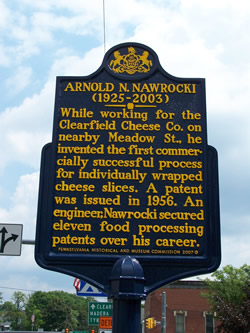

Cheese is not only popular for Americans, but also around the world. The average American eats more than 31 pounds of cheese per year. By looking into the popular history of cheese, it can be divided into two eras: before, and after Arnold Nawrocki. Who was this man? He was the one who marked a new era in the cheese industry by inventing the machine that produces the well known individually-wrapped slices (IWS). He, and a team of co-workers, did this while working for the Clearfield Cheese Company in Curwensville, Pennsylvania, in 1956.

Before the 1940s, when someone wanted to buy cheese, they had to go to the cheese market and buy a hunk, a chunk, or a slab of cheese. It was hard to get thin slices of cheese because it was time-consuming and difficult to cut them into the same size. Kraft Foods invented ribbon slices in 1940, which were essentially pre-sliced cheese. Kraft had trouble maintaining the freshness of the sliced cheese. It tended to stick together; the surface of the cheese would become hardened by the oxidation of the spoiling outer skin, and it was easily tainted with mold. Kraft and Schreiber (the other major cheese company at the time) used a process called “cold ribbon slicing” that cut and wrapped the cold ribbon slice. The cold process required enzymes and preservatives that the hot process used by Clearfield did not require. Kraft and Schreiber wouldn’t patent processes until 1970, while Clearfield Cheese patented their “hot” process IWS in which hot cheese was wrapped, molded, and cooled in 1956.

As Professor Nawrocki recalls in an email to Alan Jalowitz,

The reaction in Chicago and Wisconsin (homes to Schreiber, Kraft, and Swift) after the invention of IWS was “How did a bunch of farmers in Pennsylvania come with individually wrapped cheese slices?”

Well, my dad earned his engineering degree from Purdue and worked in research for Swift in Chicago in the late 1940s and had a few patents while at Swift. When Swift turned down his proposal for IWS, he resigned his position and six months later accepted a position with Clearfield Cheese in Pennsylvania.

My dad did not do it alone. The original equipment was built in Philadelphia but when it was shipped to Curwensville, they found it didn’t work. The local high schools did produce machinists as well as farmers so Clearfield Cheese hired a group of local machinists working with my father that finally was able to produce the machinery that successfully produced the first IWS.

So it was a bunch of machinists in Pennsylvania that beat the giant corporations.

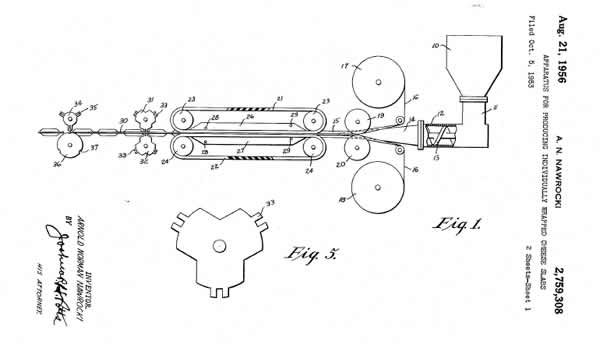

At first, Nawrocki used a wax-coated film on each side of the hot cheese; the roller pushed the cheese (still hot), and each sheet of wax-coated cellophane, until it contacted the other and was sealed. But the wax-coated film was too expensive and there was a tendency to leave wax on the cheese. Nawrocki tried the same process with cellophane, which was cheaper, but the heat of the cheese immediately wrinkled the film. Luckily, Nawrocki knew about a new type of film being researched by DuPont—a polymer-coated cellophane—which became the perfect wrapper. Moreover, he invented an easy way for consumers to open the wrapped cheese. He envisioned a slice with a four-sided seal and with loose ends beyond the seals for opening purposes. Now that the two problems were fixed, a new era of cheese began with Nawrocki’s individually-wrapped slices.

Salesmen for Clearfield had a hard time pitching the new product at first. Buyers were concerned about how much extra they would be paying for this new technology. Salesmen were forced to explain the economics and soon became frustrated. Some businesses did not believe in the product, others were enthusiasts. In an effort to further pitch their cheese, Clearfield Cheese printed “Individually Wrapped” in big, bold letters on every slice. This did not seem to improve sales. They then changed the label to “Each Slice Wrapped” and had immediate success. In response, Nawrocki said, “In this day and age it is difficult to imagine that customers apparently did not know what ‘individually-wrapped’ meant.” Eventually, however, the convenience brought comfort with the technology and Clearfield found success.

By 1970, the Clearfield Cheese Factory was the second largest cheese processor in the world (second only to Kraft), but an ill-conceived merger with Hood Dairy and the subsequent mismanagement of the cheese company quickly led to a downturn in profits. In 1985, Schreiber Foods purchased the company. The last plant that produced the Clearfield individually-wrapped cheese closed in Curwensville in 1988. Kraft, by implementing the individual-wrapping technology in the 1970s, remained the top cheese processor. Today, individually-wrapped cheese slices are an icon for Kraft foods, when it could well have been the Clearfield Singles in everyone’s refrigerators.

The technology behind these simple looking slices is amazing. This perfect technology was successfully developed after many trials and errors. During the process a group of skilled machinists took on the challenge of getting the equipment to work. Eventually, the apparatus for producing individually-wrapped cheese slabs received approval from the United States Patent and Trademark Office, recorded as patent number 2,759,308 under the name of A.N. Nawrocki.

Individually-wrapped cheese surely is one of the most innovative inventions of the 20th century. Arnold Nawrocki, who worked in the Clearfield Cheese Company in Curwensville, Pennsylvania, not only changed history, but also contributed to cheese becoming a convenience throughout the world.

Sources:

- Eskin, Blake. “Big Cheese.” The New Yorker. 80:28 (2004): 66.

- “Funding Universe.” Schreiber Foods, Inc. Jun. 2005. 2 Dec. 2009. <http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/Schreiber-Foods-Inc-Com....

- Nawrocki, Arnold. “A History of Individually-Wrapped Process Cheese Slices.” 1979. Marschall Italian & Specialty Cheese Seminars. 1 Dec. 2009. <http://www56.homepage.villanova.edu/david.nawrocki/Arnold%20Nawrocki%20I....

- Nawrocki, David. David’s Homepage. 17 July 1997. 2 Dec. 2009. <http://www56.homepage.villanova.edu/david.nawrocki/cheese.htm>.

- Nawrocki, David. Personal Communication with Alan Jalowitz. 18 Oct. 2010.

- Nusbaun, Vincent L. Zehren and D.D. Process Cheese. Green Field, WI: Schreiber Foods, 1992.

- “The History of Cheese.” The Nibble. 18 Feb. 2010. <http://www.thenibble.com/REVIEWS/main/cheese/cheese2/history.asp>