Twenty years after the eminently tragic flood in Johnstown, Cambria County left more than 2200 dead, a new dam was built in the town of Austin, Potter County, just 150 miles north. Less than two years after the last load of concrete was placed, the Bayless Dam in Austin was reduced to ruin and at least 78 lives were lost.

Before the 1911 flood, the town of Austin had already seen its share of disasters. May 31, 1889, the same day of a catastrophic flood in Johnstown, Austin also endured a flood. One year later, a fire destroyed the town. They rebuilt only to be burnt to the ground again in the fall of 1891. In May 1894, yet another flood fell upon them. The town of 2000 people was once again destroyed in the fall of 1897 by another furious fire. The people of Austin brought the town back to life time and gain, rebuilding their homes and small businesses, and hoping to carry on peacefully.

When George C. Bayless decided to build his paper mill, Bayless Pulp & Paper Company, in Austin, most of the townspeople were excited. After Austin’s lumber industry dwindled, Bayless’ plan meant more jobs. Moreover, the second-growth pulp trees were ideal for a paper mill. Some of the townspeople, such as Willie Nelson, a local grocer and one of the leading Democrats, were skeptical—while they wanted work, they didn’t fully trust a big corporation seeking cheap business.

The Bayless Dam was built by George C. Bayless to supply water for his paper mill. Bayless Dam rested along Freeman Run in north-central Pennsylvania in Potter County. This dam wasn’t Bayless’ first attempt at replenishing the flow into his mill, however. It was built to replace a previously constructed earthen dam which, according to Ronald Ebbert, president of the E.O. Austin House and Historic Society Museum, “quickly proved inadequate, so he built one out of concrete to meet water demands.” After his unsuccessful first attempt, Bayless upped the ante by setting out to build the largest concrete gravity dam in Pennsylvania. The Bayless Dam, completed December 1, 1909, came in at a cost of $86,000 (approximately $2 million in 2009 dollars).

Bayless’ engineer T. Chalkey Hatton was assigned the task of designing the concrete dam. Impressive for its time, the dam stood 50 feet tall and spanned a length of 530 feet. 15,780 cubic yards of concrete impounded 250 million gallons of water – enough water to cover the area of a football field at an astonishing 580 foot depth. The design was Hatton’s; however, the final plan that George Bayless selected for construction omitted several features that concerned Hatton deeply and would change the history of the northern Pennsylvania town forever.

It was Hatton’s desire that the dam be constructed with a cut-off wall beneath the dam. A cut-off wall is an impermeable vertical wall that runs along the length of a dam at some depth below pre-existing grade. Such a wall prevents water from flowing through the ground and underneath a dam. If water is allowed to flow below a dam, then the dam will experience uplift pressure. Uplift pressure works against gravity by lessening the effective weight of the dam and the consequence is a decrease in the amount of water that the dam can hold back. When uplift pressure is great enough a dam will no longer be able to withstand the load delivered by its design capacity. Bayless decided to cut costs by eliminating the feature. The result: catastrophic sliding failure.

Another issue that Hatton had with the chosen design was the installation of a wooden cap at the outlet of the 36 inch draw-off pipe. The function of this pipe was the quick release of water in the case that water levels approach the design maximum. With the use of a wooden cap instead of a valve cap, as was recommended by Hatton, the cap was not removable except during low-flow conditions for clean-out.

As soon as construction was completed in December 1909, visible cracks appeared vertically through the dam. High water pressure was ruled out as the cause of the cracks because, at the time, no water was held by the structure. Instead, Hatton speculated that the cause of these cracks was inadequate curing time and placement of concrete in freezing weather during the rapid construction process.

The people of Austin were in a very precarious position sitting less than one mile downstream from such an irresponsibly-designed dam, but their concerns were quelled by the common claim that the Bayless Dam was “the dam that could not break.” Austin’s residents also relied on Bayless Pulp & Paper, viewing the dam as a necessity for maintaining jobs in the struggling town.

One resident, however, was a vehement protestor of the ominous structure. Willie Nelson – no, not the country-music star – was absolutely opposed to the dam. He is reported to have made regular trips to the dam to document its condition. Eric C. Wise noted in his article in Penn Lines Magazine entitled “The Day Austin Died” that Willie, “one of the town’s leaders, grocer, and Potter County Register and Recorder,” made “daily journeys to the dam to check on the cracks” and that “his prophetic admonitions – while scorned by many – later earned him the nickname ‘the Jeremiah of Austin.’”

On January 23, 1910, just two months after the completion of the dam, Austin witnessed the first installment of the damages pending. Rain and unseasonably-warm weather caused snow melt, leading to a sharp rise in the reservoir’s level. Water began to bubble up from the ground as far as fifty feet downstream of the toe of the dam. A portion of the eastern earthen embankment slid down eight feet, allowing water to bypass the dam. Joe McKinney, one of Bayless’ employees, panicked when he saw these changes and rushed down to the town to warn his neighbors and family.

In a desperate attempt to relieve the immense pressure on the dam, dynamite was used to blow a notch along the crest approximately eight feet across and four feet below the water level. Since a valve cap was not installed on the draw-off pipe, it was required that the wooden cap was blasted as well. The combination of these efforts emptied the reservoir in around sixteen hours and major devastation was circumvented.

“At first we were scared,” remembers Olive McKinney, a survivor of the 1911 flood. “But after they emptied the dam, we all went back home—chased chickens out of the kitchen, washed the dishes, and took up life as we left it. We just wanted a chance to work and live in peace. We were afraid Bayless might shut down or move the mill.”

Although the dam held under the intense pressure of the storm surge, lasting effects were seen. The massive structure was pushed an amazing 18 inches at its base and 31 inches at its crest due to the heavy flow of water underneath the dam. Additionally, the holes blasted for pressure release were in need of repair. The looming question was: should this dam be reinstated to service?

Bayless did not shut down or move. In Engineering News of October 5, 1911, the editor writes about those individuals in charge of the dam saying,shortly afterward they concluded (on what engineering advice, if any, we know not) that the dam was still strong enough to hold water safely. The draw-off pipe was closed and the reservoir was filled again. Within a month of the original failure they had raised the water within two feet of the overflow. This produced a leakage under the dam of about 600 gallons per minute; yet no one seems to have considered that of any importance as a danger warning.

After the partial failure of 1910, Hatton, with the help of consulting engineer Mr. E. Wegmann, devised plans for dam reinforcement. They made many suggestions, such as a rock-fill reinforcement along the base on the down-stream face and a cut-off wall that reached the bedrock placed on the up-stream face. Hatton replied to an inquiry from Engineering News saying, “the plans and recommendations were submitted in February, 1910, since which date I have had no further connection with the dam and do not know what measures were taken to reinforce it.”

Along with the continued problem of water leaking under the dam’s foundation, the previously dynamited draw-off pipe was merely patched and not upgraded to a valve control system. That was not so very unusual since in 1910, dams in Pennsylvania were completely unregulated for safety. Bayless did only minimal repairs, disregarding most of Hatton and Wegmann’s suggestions. He told Hatton that the dam needed to be safe, but not two times as safe.

September 30, 1911 was a beautiful, sunny Saturday. A local election took place that afternoon. Bells and whistles rang through the streets, citizens cast their ballots. Willie Nelson tended his grocery while Agnes Murphy’s father peddled ice-cream. Mothers hung wash on the lines. Toddlers napped.

At 2:15 that afternoon the dam split.

Cora Brooks, an Austin outcast who ran a brothel, lived on a hill near the dam. She saw the dam being ripped to shreds by unrelenting surges of water and rang every telephone number she could into town to warn them. Alarms sounded, signifying the break. Ronald Ebert, president of E.O. Austin House and Memorial Society, said that “they tested the alarms several times, so people didn’t pay much attention to them when they were real.”

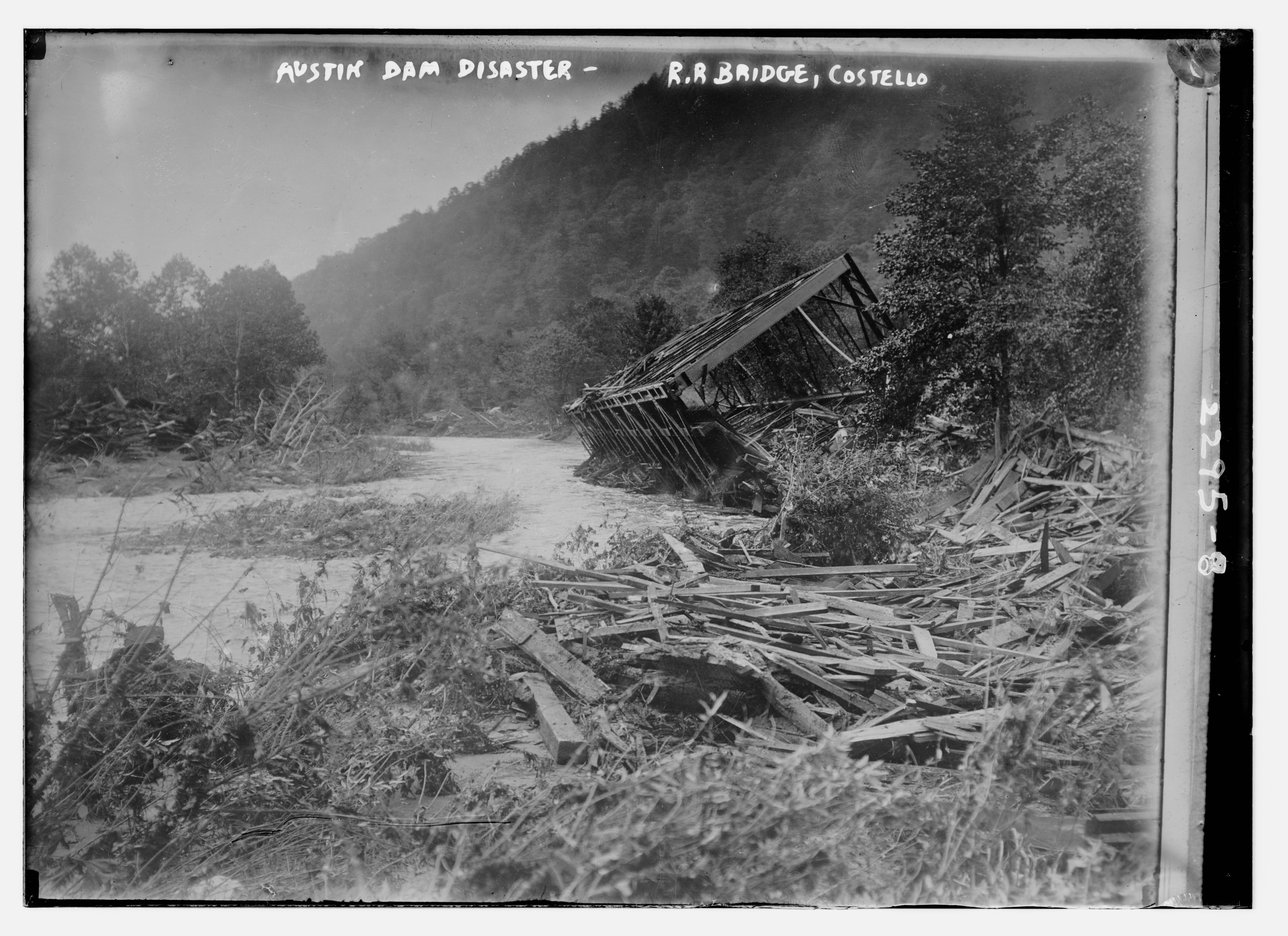

As the flood wave hit Austin roughly fifteen minutes after the initial breech, the high, raging water was not the only evil bearing down on the town. Austin was hit hard with a wave of pulpwood carried from the Bayless Mill upstream. Survivor Agnes Murphy remembers the buoyed material—”I watched all the debris go down, and all this wood in between the paper mill and the dam was coming down and it was forming clouds—just like the white clouds we have in the sky. And what a roar.”

The townspeople struggled to climb the hill to safety, desperately fighting to get over a barbed wire fence that tugged back on the women’s long skirts. Alice Ries recalls, “my father had my brother in one arm and me in the other arm and told my mother to follow. We crossed the street, went up the hill, and when we got to the top of the hill, all we could see was that our house had gone, and the church had gone—except for the steeple of the church was swirling around in the water.” Agnes Murphy, a little girl at the time, remembers the chaos of that afternoon: “Dr. Mansley came out of the hospital. He had his horse tied to the hitching post and he was pulling the hair out of his head because he knew he had lost his wife and baby. And he did.”

The town was obliterated. After all of this destruction, the worst had not yet come to pass. Gas mains, severed in the chaos, caused fires to erupt and spread throughout the broken town. The fire and overall destruction greatly impeded rescuers from reaching those possibly entrapped in the wreckage.

Those who survived the event were left to wander the streets in search of lost loved ones. “I’m a very tender person,” said Agnes Murphy years later, “and it bothered me, seeing all these horses floating down. And they didn’t know what in the world to do with all these horses—how to dispose of them. They had to keep making bonfires so to burn the flesh up. And oh, what an odor it was!” She also remembered her father finding a body behind the remains of their chicken coop. Alberta Broslet, another survivor, said, “I’ll tell you what bothers me. I found a baby skeleton in one of the ditches clear down below the Catholic church in a side stream.”

News traveled to neighboring regions and support poured in to the badly damaged town. Reports were made of death tolls in the hundreds and even thousands. While the actual number of dead will never be certain due to unrecorded immigrant workers who, according to Sandra Downs of the Tribune-Review of March 1, 1998, lived in “makeshift camps in the woods,” the number of confirmed deaths is set at seventy-eight.

United States President William Howard Taft addressed the town of Austin after the disaster, saying in a public broadcast, “I have been shocked and horrified by news of the catastrophe that has befallen your thriving village. I want to express to you my sympathy as an individual and as president of the United States. I am sure the entire nation joins me. Please wire me in Omaha as to the extent of the disaster and as to your needs.”

Pennsylvania State Senator Frank E. Baldwin had something to say as well—

I defended property rights. I believed that government should not interfere in the affairs of private business. I objected to having state inspections of the dam. I did not want anything done that might cause Bayless to move his company—move to a state more friendly to free enterprise, with fewer government bureaucrats and less red tape. Now I feel the sorrow—the tragedy of losing my parents and my sister Grace, who tried so hard in vain to save them. Experience has taught me one cannot defend property rights at the expense of human rights.

The story of the collapse of Bayless Dam in Austin is one of irresponsible actions and dramatic consequences. There was not a happy ending for the residents of Austin; however, their suffering created awareness and inspired the first dam safety regulations in Pennsylvania. According to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection Dam Safety Program, “following the devastating dam collapses in Johnstown in 1889 and Austin, Potter County in 1911, Pennsylvania enacted the first known dam safety legislation in America in 1913 providing for the regulation of dams and other water obstructions.”

The collapse of a dam in a virtually unknown town in Potter County, home to only one tenth of one percent of Pennsylvania’s population, has inspired regulation that affects not only the entire state, but the entire country.

On June 25, 1913 Pennsylvania legislators completed Act No. 555 of the Laws of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. This act provided for the regulation of dams and gave enforcement power to the Water Supply Commission of Pennsylvania (WSCP). Under this act any party interested in constructing or modifying any water obstruction must first obtain a permit from the WSCP. Maps, plans, profiles, specifications and proposed changes to a structure must be provided to and approved by the WSCP to avoid legal penalties of up to a one-thousand dollar fine and one-year of jail time. Any responsible party in non-compliance with this act will face these misdemeanor charges and ultimately be responsible for the cost of necessary modifications to their structure. The passing of this act signifies the beginning of a time where liability is attached to in hands in which our lives rest.

“It’s been eighty-six years since this happened,” reflects Alice Ries. “All of my friends, family, and relatives were concerned that as a small child, seeing all these tragedies—broken bodies, mangled bodies, and so on—that would have a terrible effect on my life. But it didn’t because my father sat down and talked with me and told me that tragedy was a part of life and we couldn’t ignore it, we couldn’t avoid it, but we couldn’t let it affect our whole lives. We had to go on.” Once again, the devastated but hopeful townspeople of Austin began to rebuild their town.

Pennsylvania currently regulates approximately 3,200 dams and reservoirs. The state oversees projects from planning and design to construction and continued maintenance in order to ensure that nothing like what happened on that horrible day in Austin can ever be allowed to reoccur.

Sources:

- Austin Dam Memorial Association. Austin Dam Memorial Association. 2009. 27 Feb. 2010. < http://austindam.net/>.

- Beebe, Victor L. History of Potter County, Pennsylvania. Coudersport, Pa.: Potter County Historical Society, 1934.

- “Dam Safety.” Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. 2010. 1 Mar. 2010. <http://www.depweb.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/dam_safety/10501>.

- Downs, Sandra. “The Austin Flood Remembered.” Tribune-Review 1 Mar. 1998. Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. 25 Feb. 2010. <http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/events_that_sha....

- “It is a Crime to Design a Dam without Considering Upward Pressure: Engineers and Uplift.” ASCE Conf. Proc. 128.16 (2003): 1890-1930.

- “Laws of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.” C.E. Aughinbaugh, Harrisburgh, PA (1913): Act No. 555. p.555- 558.

- The Austin Disaster, 1911: A Chronicle of Human Character. By Gale Largey. 2003. DVD.

- “The Failure of a Concrete Dam at Austin, Pa., on Sept. 30, 1911.” Engineering News 66.14 (1911): 419-22.

- “The Partial Failure of a Concrete Dam at Austin, Pa., on Jan. 23, 1910.” Engineering News 66.14 (1911): 417-18.

- Wise, Eric. “The Day Austin Died.” Penn Lines Magazine 40.9. Sept. 2005: 8-11.