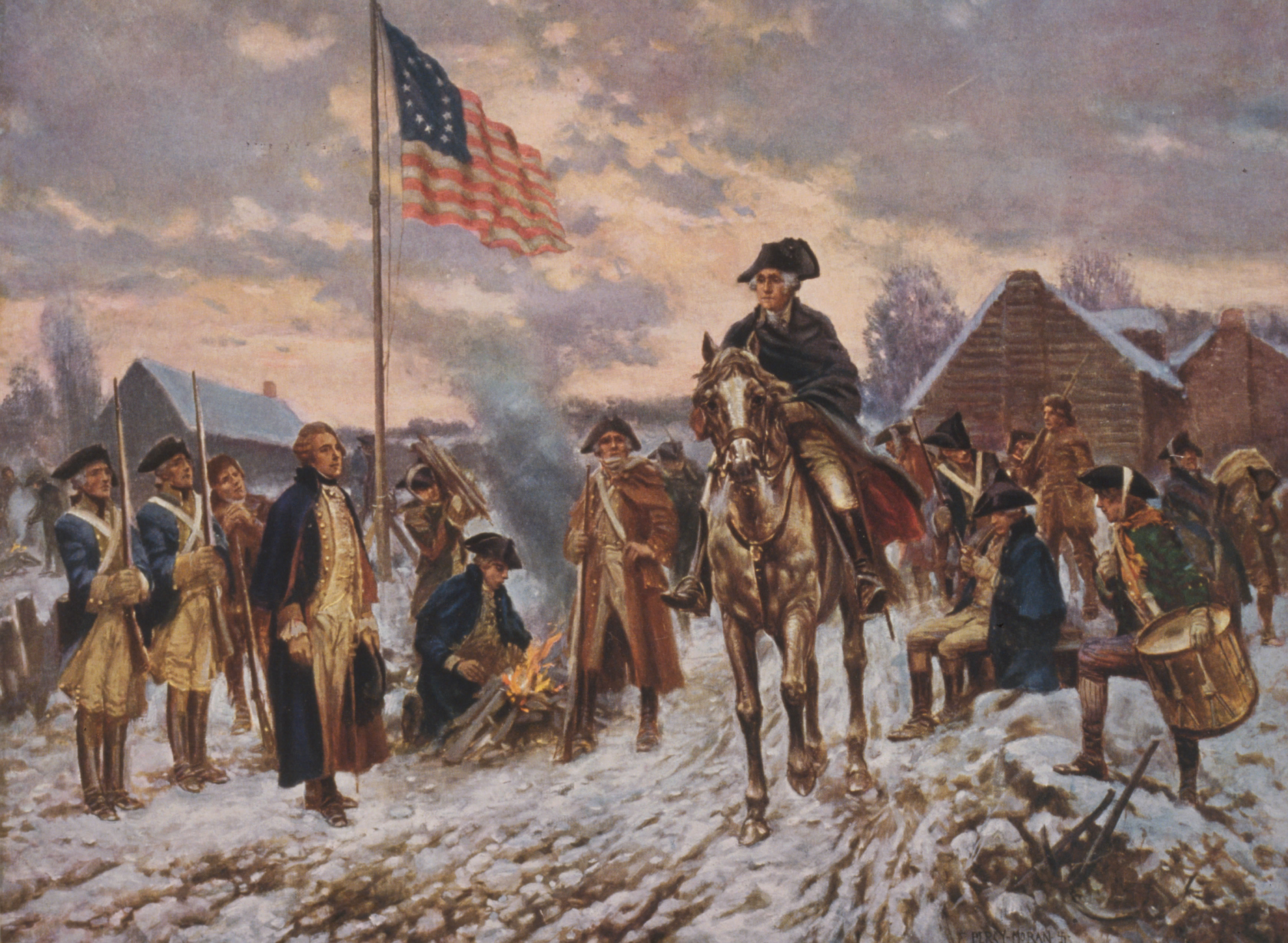

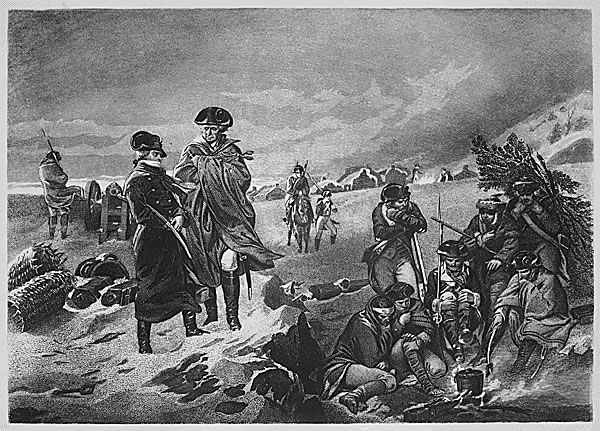

The voices of the past haunt the luscious green hills of Chester County. Although never a battlefield, Valley Forge claimed the lives of hundreds of American Revolutionary soldiers during the encampment of 1777-78. This camp had a higher death toll than the battles at Brandywine and Germantown combined. It is a place where thousands of soldiers endured hunger, disease, and bitter cold; against all odds they struggled through adversity to fight for the nation’s freedom and independence. This is a place where General Washington’s soldiers prevailed over hardships, and because of their commitment, it became a turning point in the Revolutionary War. As John B.B. Trussell, Jr. writes in Epic on the Schuylkill, “It was a triumph of endurance and dedication over starvation, nakedness, cold, disease, and uncertainty…For generations of Americans, Valley Forge has provided a symbol of patriotic devotion, epitomizing the ideal which brought our nation into being.”

Before a full understanding of the significance of Valley Forge can be gained, it is useful to know how this strategic location fit into the setting of the war. In the fall of 1777, the British army decided to take the patriots’ capital, Philadelphia. Therefore, they sent over 15,000 troops to Philadelphia and General Washington decided to march his 8,000 Continentals and 3,000 militia from New Jersey to fight the British at Germantown, Pennsylvania, about six miles northwest of Philadelphia. Sir William Howe, the leader of the British forces at Germantown, had only seven or eight thousand troops with him; however, Howe had the lay of the land on his side. Germantown had natural defenses such as ravines, hills, and streams, and the town’s characteristic stone houses afforded additional protection.

Despite these barriers, Washington’s forces managed to deliver a solid blow to the British. One of the British light infantry veterans, Lieutenant Martin Hunter, said his battalion “was so reduced by killed and wounded that the bugle was sounded to retreat; indeed, had we not retreated at the very time we did, we should all have been taken or killed.” As John Buchanan writes in The Road to Valley Forge, “The fury of the American attack broke the light infantry, and there occurred a rare sight in the Revolutionary War: British regulars showing their backsides as they fled the field in wild disorder.”

As the American troops pursued the British, additional British forces came forward, which left the Americans to fight, in General Sullivan’s words, for “every yard House & Hedge.” The Americans were stymied by the British retreat into Chew Mansion, a stone “castle” that Washington’s forces could not penetrate with their artillery. As two other American divisions heard the fire and turned around to help, they grew confused in the fog and fired on each other, eventually causing both groups to flee. British General Cornwallis brought reinforcements from Philadelphia, which pursued but never managed to engage Washington’s forces. By the end of the day, Washington’s forces had marched forty-five miles, with 152 killed, 521 wounded, and 400 captured or missing, resulting in another American defeat.

According to Buchanan in The Road to Valley Forge, although the rebels may have lost Philadelphia, “The American army came out of Germantown believing in itself.” Major Henry Miller, 2nd Pennsylvania, acknowledged:

Our army is in higher spirits than ever, being convinced from the first officer to the soldier, that our quitting the field must be ascribed to other causes than the force of the enemy: for even they acknowledged that we fled from victory.

With an increased confidence in their combat abilities, the Continental Army needed to set up a camp from which they could both battle the cold and launch a winter campaign to regain their capital. By mid-December, Washington picked Valley Forge, a decision that cost him “more reflection or consideration” than any other in his whole life. Valley Forge had ample natural defenses; a river protected one side, while two creeks provided a natural blockade that would create problems for anyone approaching. Soldiers trying to attack would have to charge up-hill, putting them at a distinct disadvantage. At the same time, Valley Forge, approximately twenty miles outside of the city, was close enough to Philadelphia that Washington could sustain pressure on the British.

After the 11,000 soldiers (over 2,000 of them barefoot) marched for seven hours to Valley Forge on December 19, 1777, they started to build cabins to occupy, to cook meals of their own creation, and to fashion their own provisional gear and clothing. In order to speed up the cabin-building process, Washington offered a twelve-dollar prize for the first well-constructed hut in each regiment. As soldiers rushed to build their huts, many were forced to dig their floors up to two feet below ground level in order to conserve heat and reduce their supply usage. These attempts to escape the cold unintentionally allowed a dampness that bred disease. John B.B. Trussell, Jr., in the Epic on the Schuylkill, notes that “By December 23, lack of shoes or clothing had made 2,898 men unfit for duty.” New York Continental Congress member, Gouverneur Morris, enlightened the public about the soldiers at Valley Forge by describing them as “an army of skeletons…naked, starved, sick and discouraged.” General Washington described this undernourished troop as “unfit for duty because they are barefooted and otherwise naked.”

Buchanan notes that the army’s malnutrition cannot be blamed on “Valley Forge being far from sources of supply. Copious supplies of food were nearby. Gristmills abounded…the harvest had been abundant.” He maintains that “at Valley Forge the problem was the all-important logistical system.” The system of transporting supplies lacked the infrastructure necessary to ensure soldiers were fed and equipped properly. Valley Forge’s naturally defenses made it challenging to transfer supplies there; the Schuylkill River was blocked with ice for most of the winter and the roads were so treacherous that the Continental Congress could not pay teamsters enough to carry wagons of supplies to Valley Forge. General Thomas Mifflin, who was in charge of the transportation, also posed a problem. Mifflin preferred the glory of the battlefield to the tedium of logistics, so he ignored his job and the problems that came with it. By Christmas, General Washington was compelled to write:

I am now convinced beyond a doubt that unless some great and capital change suddenly takes place in [the Commissary Department] this Army must inevitably be reduced to one or other of these three things. Starve, dissolve, or disperse, in order to obtain subsistence in the best manner they can. Rest assured…this is not an exaggerated picture, but that I have abundant reasons to support what I say.

The Pennsylvania winter caused the soldiers to feel keenly the lack of clothing and food. As Buchanan writes, “the food supply remained sporadic throughout the winter, at times approaching a feast-or-famine regimen,” which was only “surpassed as a problem by the lack of proper clothing.” By the fifth of February, nearly four thousand men lacked either clothes or shoes, making them unfit for duty. In terms of supply shortages, the lowest point at Valley Forge occurred in mid February, when Colonel Richard Butler of 9th Pennsylvania wrote there was “not a blanket to Seven men” and Colonel Philip Van Cortlandt, commanding 2nd New York, declared that only about thirty men were fit for duty as the rest were “Sick or lame, and God knows it wont be long before they will all be laid up, as the poor Fellows are obliged to fitch wood and water on their Backs, half a mile with bare legs in Snow or mud.” It was not until Nathanael Greene took over the quartermaster’s post in March of 1778 that the supplies began to come into the encampment on a regular schedule. Greene’s success was due in part to his “healthy sense of economic realism,” a characteristic that led him to conclude that the Revolution would “terminate in a war of funds” in which “the longest purse” would triumph.

It was not only the cold and the hunger that plagued the encampment, but also disease. The most common killers of the troops were typhus, dysentery, influenza, and typhoid. Most of the soldiers’ illnesses could be tracked back to poor personal hygiene and unhealthy sanitation. Although officers were ordered to check cabins twice daily for cleanliness, excavations at Valley Forge indicate that most soldiers simply threw the remains of their meals into the corners of their huts. The combination of crowded cabins, unwashed bodies, and decaying refuse greatly contributed to the unsanitary conditions at camp. The soldiers who died were often stripped of their clothing, which was then passed on to other soldiers, spreading even more disease. An estimated 3,000 soldiers died, and almost 70 percent of those deaths occurred during the warmer months of spring, not winter. On June 17, only two days before departing camp for good, Washington reported that about 2,300 men were sick—which was over 18 percent of the troops stationed at Valley Forge. Although sickness was a constant problem at Valley Forge, without Washington’s demand for better sanitation, which involved the use of latrines and the burial of offal, the prevalence of sickness and death could have wiped out the colonial army.

Despite deprivation and disease, Buchanan asserts “the American army was a revolutionary force, and like all such armies it knew how to suffer…the Cause burned brightly among them and in a large part made them forsake home and loved ones.” Quoted in the “Diary of Surgeon Albigence Waldo,” Lieutenant Samuel Armstrong proclaimed that “Men never bore up with such bad Usage before, with so little Mutiny…indeed there was more mutiny among the Officers than among the men.”

The army at Valley Forge was not remarkable just for its spirit, but also for its diversity. The soldiers that made up the Continental Army came from a variety of different backgrounds with their own individual skills and talents. The rich and poor, young and old, and freemen and slaves fought together side by side. Until the Vietnam War, George Washington’s army remained the most racially diverse and integrated group of soldiers of any conscripted American military. The Continental Army had approximately 5,000 soldiers that were of African descent and many Native Americans that played a crucial role for the troops. For slaves, serving in the army was a way to earn their freedom. For the freemen, it was a way to earn money and boost their social standing in their community. By 1777, whites and blacks fought against the same enemy, side by side.

The soldiers at Valley Forge may have had revolutionary spirit and brotherhood, but they lacked the experience of a trained army. Therefore, the most significant result of the encampment was the Continental Army’s growth into a more skillful and confident force. On February 24, 1778, a former Prussian captain, Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, referred to by Buchanan as “the leading expert on the military arts,” arrived at Valley Forge. A month after his arrival, von Steuben began training the army to become a more efficient, skillful marching mechanism. Despite a lack of equipment, the Prussian found at Valley Forge “a tough, dedicated, seasoned force lacking only the attention to its arms and accoutrements and the drill and discipline of the parade ground that would turn it into a finished product.” According to Buchanan:

Von Steuben taught officers and men not only how to maneuver on a battlefield from column to line and back again with ease, but also how to march compactly and arrive on the field as a tightly knit force instead of in long, straggling files, thus losing precious time in forming to fight.

While von Steuben trained the American soldiers in the European style, he quickly realized he needed to adapt his instruction to their unique tempers. As he wrote to a European friend, “You say to your soldier, ‘Do this,’ and he doeth it; but I am obliged to say, ‘This is the reason you ought to do that’; and then he does it.” He motivated and inspired the troops to a new sense of objective and purpose, which led to his appointment as inspector general by the end of April.

By late spring, the Continental Army was a completely different force. According to Buchanan, von Steuben’s training, “passed on to recruits by officers and sergeants and privates who had been there, lay at the root of the achievement of the regulars in formal combat situations.” On June 19, 1778, Washington and his troops departed Valley Forge. They marched a mile away from Philadelphia, ready to strike against the Redcoats. With the suffering they endured at Valley Forge still fresh in their minds, the fierce Continental Army and the British Army clashed on June 28, 1778, at Monmouth Courthouse. Though there was no clear winner at this battle, the retreating Redcoats were astonished at how evenly the two armies were matched. The war would continue for another five years, but the morale and confidence the soldiers gained from Valley Forge continued with them for the remainder of the war.

Although Washington and his army never returned to Valley Forge, the memories of their sacrifice at the encampment live on. Today, Valley Forge is a national historical park visited by people from all across the country. On display are Washington’s original, fully restored stone headquarters, reconstructions of the soldiers’ log huts, monuments to famous Revolutionary War figures, such as Baron Friedrich von Steuben, and re-enactments of the winter at Valley Forge. Visitors can participate in an educational and recreational experience that includes 26 miles of trails and a variety of programs, from engaging stories of history to the March Out Commemoration in June. In Trussell’s words, the very idea that Valley Forge National Park stands to memorialize the winter of 1777-1778 marks the “triumph of endurance and dedication over starvation, nakedness, cold, disease, and uncertainty,” providing generations of Americans with “a symbol of patriotic devotion, epitomizing the ideal which brought our nation into being.”

Sources:

- Bodle, Wayne. The Valley Forge Winter. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State UP, 2002.

- Buchanan, John. The Road to Valley Forge. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2004.

- Butler, Richard. “Colonel Richard Butler to Thomas Wharton Jr.” Letter. 12 Feb. 1778. André de Coppet Collection, Box 4, Fldr. 71, Princeton University Library, Princeton, New Jersey.

- Commager, Henry Steele and Richard B. Morris. The Spirit of ‘Seventy-six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants. Vol. 1. Indianapolis: The Bobbs Merrill Company, Inc., 1958.

- Greene, Nathanael. “Nathanael Greene to William Greene.” 7 Mar. 1778. The Papers of General Nathanael Greene. Vol. 2. Chapel Hill, NC: U of North Carolina P, 1980. 300-04.

- Kitsko, Jeffrey J. “Valley Forge National Historical Park.” Pennsylvania Highways. 2009. 7 Apr. 2009. <http://www.pahighways.com/>.

- Scott, Carole Elizabeth. “An Army of Skeletons.” Clopton Family Genealogical Society and Clopton Family Archives. 3 Sept. 1999. 7 Apr. 2009. <http://homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~clopton/index.html>.

- “Stories from PA History.” ExplorePAhistory.com. 7 Apr. 2009. <http://explorepahistory.com/index.php>.

- Taylor, Frank H. Valley Forge: A Chronicle of American Heroism. Valley Forge, PA: Daniel J. Voorhees, 1922.

- “Valley Forge.” National Park Service. National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior. 7 Apr. 2009. <http://www.nps.gov/index.htm>.

- Van Cortlandt, Philip. “Colonel Philip Van Cortlandt to George Clinton.” 13 Feb. 1778. Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York, 1777-1795, 1801-1804. Vol. 2. New York: Wynkoop Hollenbeck Crawford, 1900. 843-44.

- Von Steuben, Friedrich Wilhelm. “Baron Friedrich Wilhelm Von Steuben to Baron von der Goltz.” Rebels and Redcoats: The American Revolution through the Eyes of Those Who Fought and Lived It. New York: De Capo, 1987. 307.

- Waldo, Albigence. “Valley Forge, 1777-1778. Diary of Surgeon Albigence Waldo, of the Connecticut Line.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 21.3 (1897): 299-323.

- Washington, George. “George Washington to the President of Congress.” 23 Dec. 1777. The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799. Vol. 10. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Print Office, 1931. 192-93.

- Watts, Henry Miller. “A Memoir of General Henry Miller.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 12.3 (1887): 425-31.