Thirty-five miles south of Pittsburgh, situated on the Monogahela River in Fayette County, is the 2,300-person town of Brownsville. Within its limits stands an engineering feat that has gone unnoticed by most for many years—the Dunlap’s Creek Bridge. The bridge is one of many along the National Road, America’s first national highway. Completed in 1839, Dunlap’s Creek Bridge was the first cast iron bridge built in the United States, and it continues to withstand the test of time, carrying heavy vehicular traffic daily. It remains an important part of American and engineering history.

Brownsville was once home to many different industries and rivaled Pittsburgh in size and growth. There was once a time when westward travelers cut through Brownsville on their journey. The Cumberland Road, or the National Road, built between 1811 and 1818, passed through Brownsville on its route from Cumberland, Maryland, to Wheeling, West Virginia. The National Road further extended into the new western territories, making it an important route for industry and trade, allowing towns along the road to prosper.

Before the National Road was constructed, there was already a bridge at the crossing of Dunlap’s Creek. Constructed of timber, this bridge was washed away in a flood in 1808. Hired to design a replacement for the timber bridge, James Finley, a pioneer in the building of suspension bridges, proposed a bridge that was supported by wrought iron chains. Although Finley would go on to design many successful suspension bridges, his bridge in Brownsville would only last until 1820, when the bridge gave way under a team of six horses during a snowstorm. The driver and four of the horses survived the crash; two of the horses perished. After the collapse, another timber bridge was erected to span the gap. Although this bridge would not fail structurally, by 1832, the road surface and condition of the bridge caused alarm.

During the 1820s and early ‘30s, the U.S. Congress was slow to fix the deteriorating National Road and its bridges. In 1832, the states through which the National Road passed agreed to take over the maintenance of the Road with one stipulation: the road was to be repaired one last time by the federal government. The government agreed, and the Army Corps of Engineers led by Captain Richard Delafield was called in to complete the task.

Captain Richard Delafield was a graduate of the United State Military Academy. At West Point, he learned engineering in the French style that employed a mathematical and scientific way of learning. Although his education was mainly French, those at West Point would have also been familiar with the English style that was based more on practical and field knowledge. Delafield would work on many projects in the United States and his peers later commented on his “extensive and varied knowledge.” After constructing the Dunlap’s Creek Bridge, Richard Delafield became the Army Corps Chief of Engineers and a superintendent at West Point.

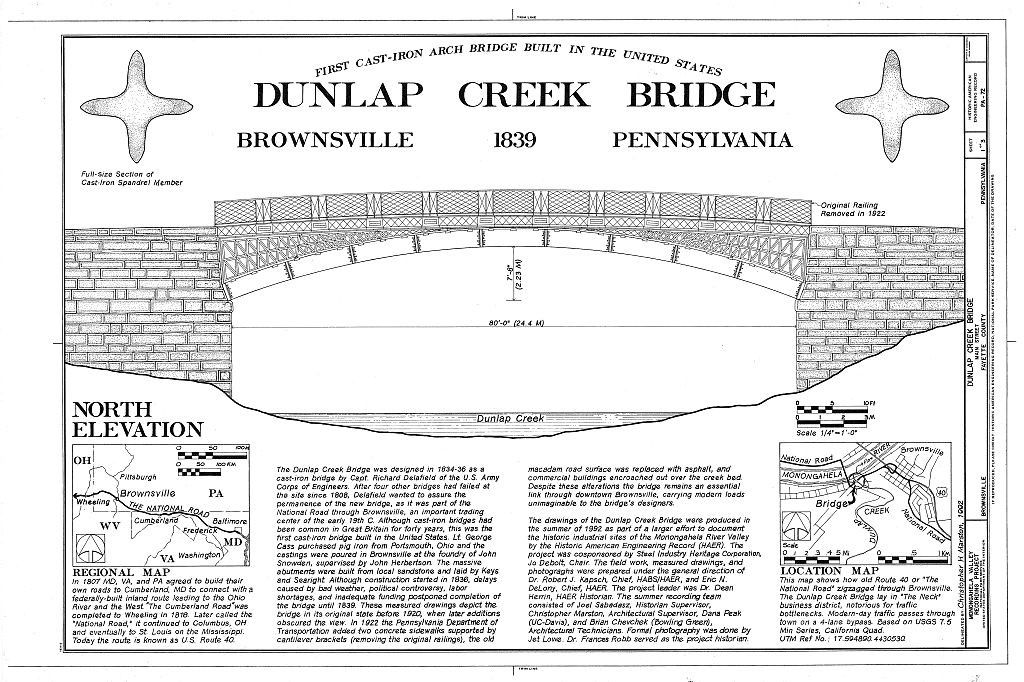

Delafield’s bridge would need to span 80 feet and accommodate the steeply sloped banks at the site. Initially, Delafield was against building a bridge because the government had not built one at the site when the National Road was originally created. Secretary of War Lewis Cass agreed with Delafield, but they were overruled and a new bridge was to be built.

Since Capt. Delafield was forced to build the bridge, he wanted to move its placement, sending the adjoining town of Bridgeport into an uproar. Bridgeport believed that the new placement of the bridge would divert any and all traffic away from them, hurting their economy and town. Eventually, Delafield would lose yet another battle, and the bridge would be built where the three previous structures had been. He decided to construct the bridge of cast iron rather than stone, as he felt the thrusting forces of the arches would be too much for stone. Timber was also ruled out because of decay and risk of fire. Iron was readily available and Brownsville’s foundries were able to handle the castings.

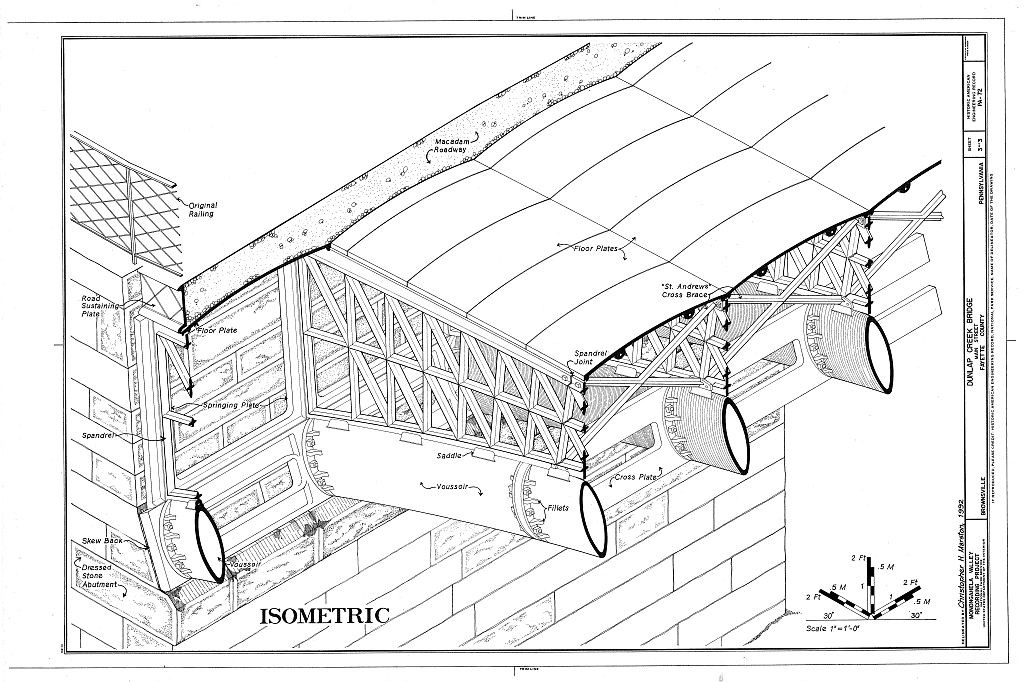

The design for the bridge was to be a single span comprised of five tubular arches. These arches would be set upon limestone and sandstone supports, or abutments, and wing walls on the creek’s banks. Before construction began, Delafield looked for a contractor to build the abutments and wing walls. In a classified advertisement he wrote himself, he called for the best quality of stone and work so that the supports could withstand the weight of the bridge and the earth. The firm of Searight and Keys would land the contract to construct the stone abutments.

Delafield purchased the iron for the castings from Ohio and had it shipped to the foundries in Brownsville to be cast. Overall, the bridge would take 250 castings to complete, but finishing the castings would not be the reason construction took longer than expected. When designing the arches Delafield made all five arches identical in an attempt to standardize the pieces and to make them interchangeable. Placed upon the arches were the pieces that would hold the road surface. These pieces spanned from one arch to another, and were slightly curved. Lastly macadam would create the road surface and cast iron would form the railings.

Construction began in the summer of 1836 with the building of the wing walls and abutments by Searight and Keys. Work went smoothly in the beginning, and by the fall one abutment was complete and the Snowden foundryhad completed all of the castings for the bridge. Three hundred thousand pounds of iron, purchased by Delafield himself, were cast into the pieces that would make up the bridge. By this time, Dunlap’s Creek Bridge was the last repair the federal government needed to complete before handing the National Road over to the individual states.

With the construction running smoothly, the bridge should have been finished quickly. Scheduling issues and rising labor costs caused delays in the construction. Because of the delays, Lieutenant George Cass would lament, “Everything seems to have gone wrong since the commencement of this work and I do hope that I may never have such another job in my life.” Not all issues were man-made, as the weather also hindered construction. Despite many delays, the bridge was mostly completed by July of 1838. Although the bridge was structurally sound and vehicular traffic was allowed to cross, the bridge would not be officially completed for another year, on July 4, 1839.

It was at this time that the Brownsville Observer remarked about the bridge, “We cannot on this occasion omit the expression of our surprise, at the neatness with which the castings of the bridge have been executed.” Sherman Day, author of Historical Collections of the State of Pennsylvania, would later call Dunlap’s Creek Bridge “the most splendid piece of bridge architecture in the United States.”

With all of the delays and problems faced throughout construction, the bridge was completed and the final price tag came to $39,811.63. One hundred and ten years after the bridge was finished, army engineers stationed in Pittsburgh completed an estimate for the cost of the bridge in 1949. The price came to $272,925, which was vastly different from when the bridge was completed.

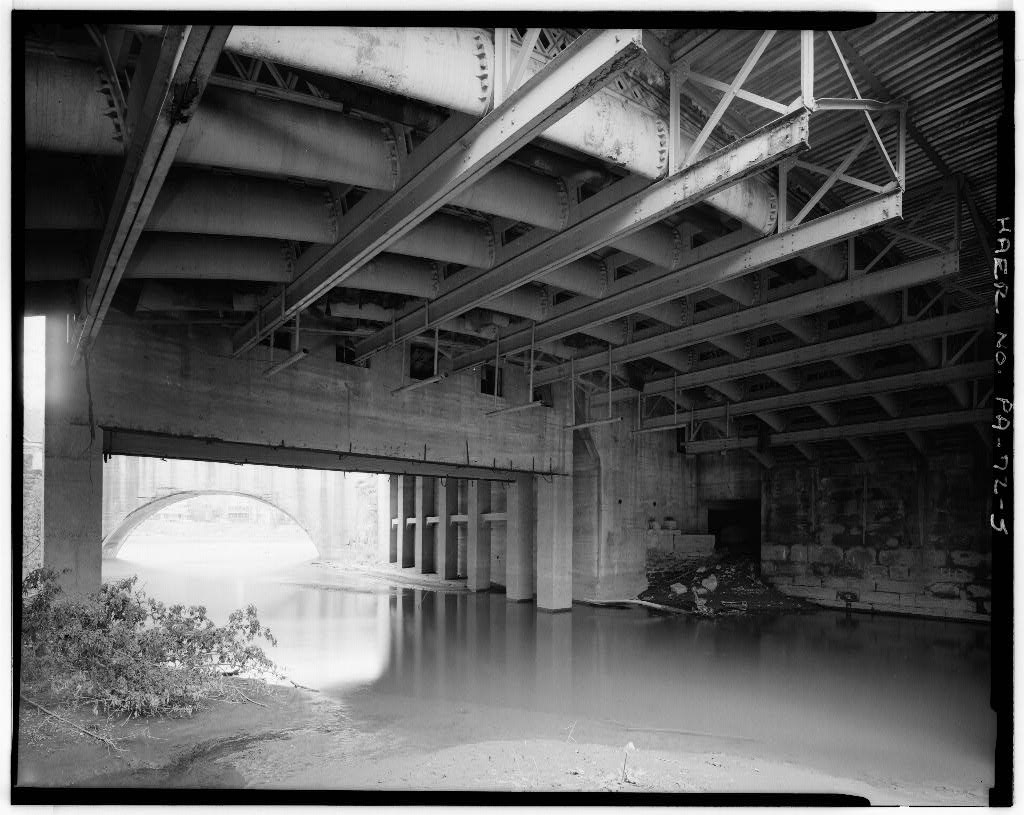

In the 1920s, the bridge received a facelift that included new railings and sidewalks added to the structure. The bridge was still structurally sound and the new sidewalks and railing were attached to the old structure by steel beams hung from the cast iron arches. Since those additions, there has been no new construction, and it still carries traffic today: a weight that Delafield himself could not have imagined.

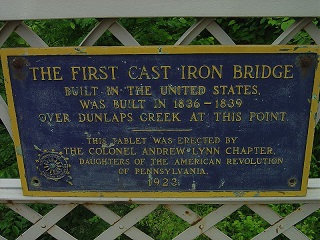

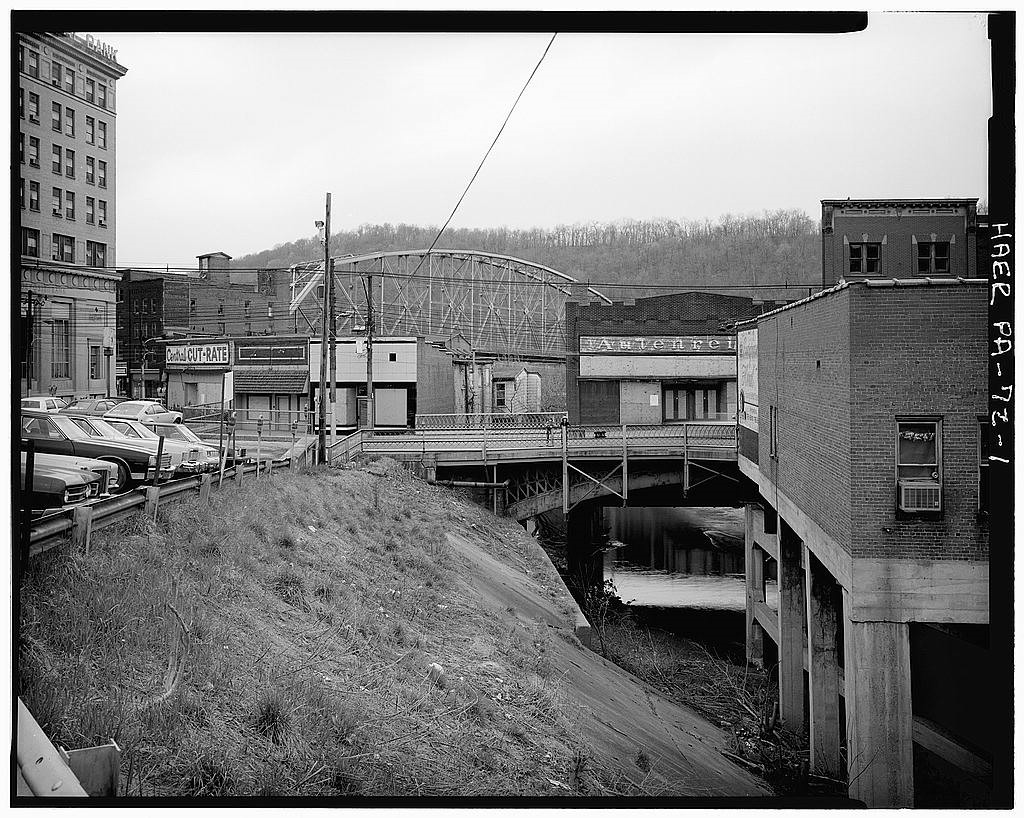

Dunlap’s Creek Bridge was a major thoroughfare for many years, and passersby marveled at the bridge. Eventually train tracks would run through Brownsville and the National Road would be less travelled. Brownsville was growing at a rapid pace after the completion of the bridge and land was coveted. When the downtown area ran out of land, the town began to build up against and above the creek, obscuring the bridge from public view. The addition of new sidewalks further hid the bridge. Although the bridge was not easily viewed, the bridge was nominated for the National Registry of Historical Places in 1977. The American Society of Civil Engineers bestowed a similar recognition. In 1923, a local branch of the Daughters of the American Revolution attached a plaque to the bridge railing commemorating the bridge’s significance.

In Brownsville today, most old buildings have been demolished or are in need of major repair. In a change of spirit and an attempt to revitalize, the town has removed the buildings that blocked the view of the bridge. Brownsville’s former mayor, Norma Ryan, claims that the bridge is the town’s claim to fame and believes that, if the views to the bridge are restored, bridge enthusiasts from all over will come to see the first cast iron bridge in America.

The bridge will remain historically important. As the American Society of Civil Engineers states, Dunlap’s Creek Bridge, “remains a testament to American ambition and integrity.”

Sources:

- “The Cast Iron Bridge.” The Daily Pittsburgh Gazette 16 Nov. 1838: 2.

- Delafield, Richard. “To Stone Masons.” The Daily Pittsburgh Gazette 8 May 1835: 3.

- “Dunlap’s Creek Bridge.” Dunlap’s Creek Bridge. American Society of Civil Engineers, n.d. 2014. <http://www.asce.org/People-and-Projects/Projects/Landmarks/Dunlap-s-Creek-Bridge/>.

- Hansen, Brett. “Assembling the Cast: The Dunlap’s Creek Bridge.” Civil Engineering (2009): 36-37.

- “Historic Landmark Takes Spotlight.” Washington Observer-Reporter 15 May 1979: 32.

- Marston, Christopher. Dunlap Creek Bridge. Digital image. Library of Congress. Monogahela Valley Recording Project, n.d. Web. 16 Feb. 2014.

- Mullooly, James. “Snowden Family Pioneered in Developing Brownsville.” Washington Observer-Reporter 16 Sep. 1970: 17.

- Robb, Frances C. “Cast Aside: The First Cast Iron Bridge in the United States.” The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology 19.2 (1993): 48-62.

- Robbins, Richard. “Brownsville Celebrates 1839 Dunlap Creek Bridge.” Greensburg Tribune Review 3 July 2009: n. pag.

- Rosenblatt, Edith. “First and It Lasts.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 24 Apr. 1949: 116-17.

- United States. National Park Service. Department of the Interior. Dunlap’s Creek Bridge. By Historic American Engineering Record. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Print.