The date was June 24, 1750. They had argued for weeks over a new growing concern. From lands far overseas, they were beginning to feel threatened. Preemptive action was the best solution for this crisis in the making. England couldn’t afford to have its American colonies become technologically independent. Every day, the colonies were becoming more of a global power in exports and while England risked being left behind. Worse yet, the colonies claimed they had invented this “iron rolling mill.” It was decided; Parliament must pass the Iron Act of 1750.

The Iron Act of 1750 was part of a series of acts passed by the English Parliament against Colonial America to limit independent technology use and growth. This law decreed that the colonies were no longer permitted to manufacture their own products from raw materials, and that everything used in the colonies was to be a “Made in England” product. Seen as a blatant attempt to curb colonial iron production, England was ordering America to abandon its massive iron manufacturing market despite the fact the colonies accounted for over 1/7th of the world’s total iron supply. The colonies had grown weary of these outrageous laws, beginning with the suppressive Navigation Acts England passed in 1650 that prohibited America from trading with certain countries. Fed up with the unfair treatment from England, America openly defied this Iron Act, and invented many industrial processes that have become the basis for mass manufacturing today. All of this defiance – all of this industrial knowledge – began with a simple, and often overlooked invention of the iron rolling mill by John Taylor in the small town of Chester, Pennsylvania in 1746.

John Taylor was a simple man whose began his professional career as a physician and surveyor. Taylor began his work in the manufacturing field when he became partners with his brother-in-law Samuel Savage. By 1737, Savage had become the owner of the Warwick Furnace due to a family inheritance. Seeking to expand his business, Savage convinced Taylor to set up the Sarum Ironworks in 1739 as a plant to receive the iron from the Warwick Furnace. This partnership stood to be a very profitable venture due to the advanced ironworking technologies in the region. According to Swedish Historian Israel Acrelius, who resided in colonial America from 1750 to 1756, in his book History of New Sweden, “Pennsylvania, in regard to its iron works, is the most advanced in all the American colonies.”

Unfortunately, this partnership did not last long, and Samuel Savage passed away in 1742. By this time, the Sarum Works stood as one of the best ironworks in the region, alongside with the Forge of Crum Creek two miles away. Then on June 24, 1746, Sarum Ironworks created the world’s first iron rolling mill, a manufacturing feat which would attract international attention in the coming years.

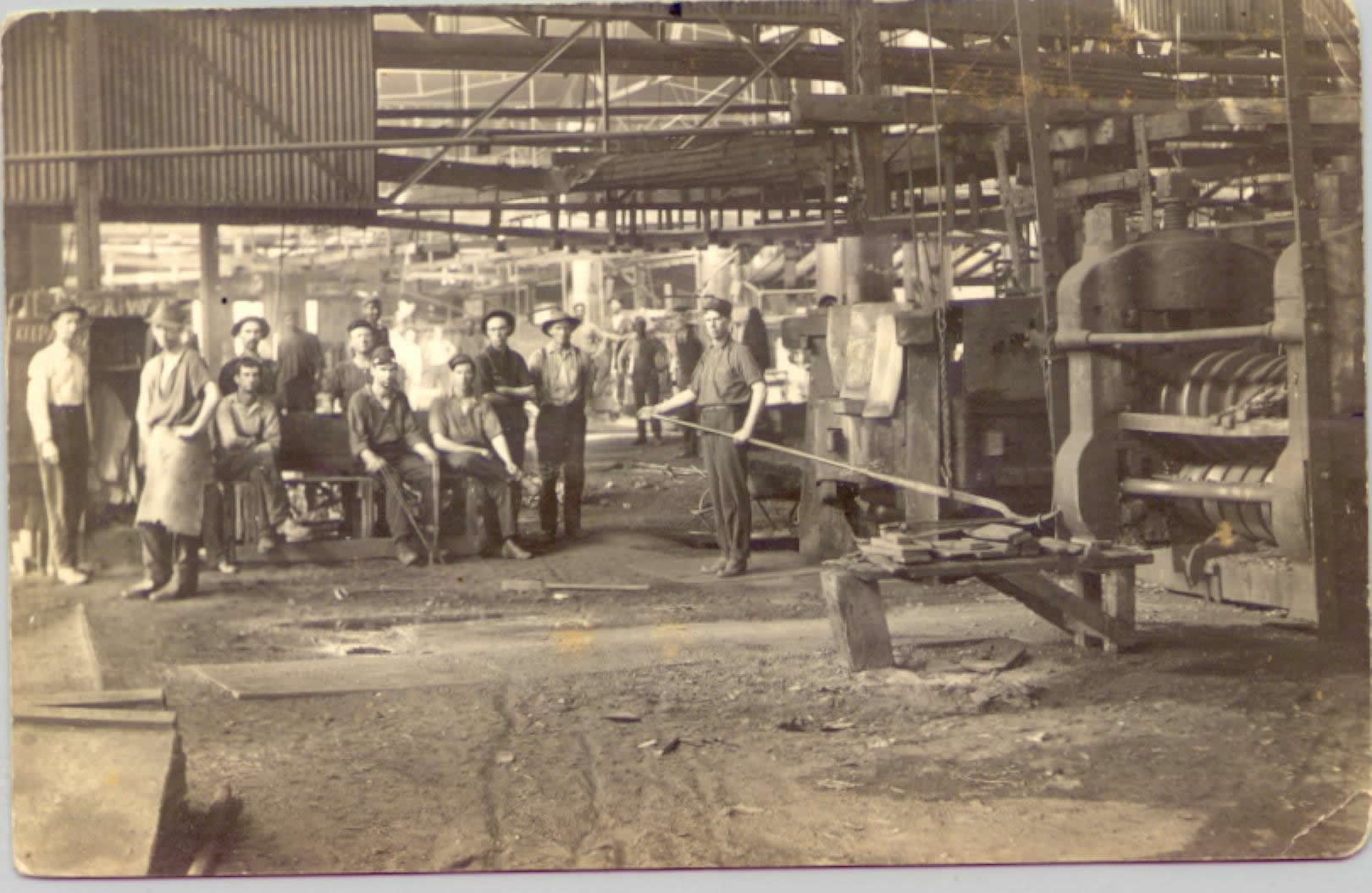

The Sarum iron rolling mill used a technique known, as the name implies, as iron rolling. The initial iron rolling methods used a process where an iron sheet or bar was passed through a pair of strong metal rollers. By passing through the rollers, the iron becomes much denser and has better surface features, which lead to higher quality manufacturing products. Depending on the intended use of the product, iron rolling can be done at hot or cold temperatures to create ideal metal conditions. This revolutionary concept allowed Sarum Iron Works to mass produce iron bars, nails, and countless other finished goods at high quality for significantly cheaper prices than anywhere else in the world. When English merchants in Liverpool learned of these cheap goods, nationwide concern began to spread that resulted in the passing of the 1750 Act.

While John Taylor’s iron rolling mill represented a historic first in the manufacturing world, it was actually many years before the general public learned he had created this invention. As a stipulation of the Iron Act, all local acting sheriffs were ordered to search their precincts to find any local forges or metal work plants that violated the newly passed law. Specifically, the Iron Act called for the inspection and documentation of, “every mill or engine for slitting or rolling iron, every plating forge to work with a tilt hammer, and every furnace for making steel which were erected within their several and respective counties.” So, in 1751 Sheriff John Owen made his rounds through the Chester County area on the orders of Governor James Hamilton. In this search, Sheriff Owen reported:

“There is but one mill or engine for slitting and rolling iron within the country aforesaid, which is the situate in Thornbury Township, and was erected in the year 1746 by John Taylor, the president proprietor thereof, who, with servants and workman, have ever since the 24th day of June last used and occupied the same.”

This statement serves as the main basis for the invention date of the Sarum iron rolling mill, though many historians and locals at the time claimed that the iron mills had been long standing prior to 1746. But looking back at the Sarum mills, the 1746 date is still given as the official invention date due to the high level documentation of the subject from Sheriff Owen’s report and the collection of all further Tax Act data.

This discovery came as quite a shock to many colonial residents, since the first iron mill was thought to actually have been found in Middleboro, Connecticut prior to this search. The Middleboro plant had been erected in 1751, a full five years after the first documented record of the Sarum iron rolling mill.

Despite the rigorous identification efforts of the Iron Act, the law was widely ignored due to loose enforcement from local governing and British officials. After sheriffs completed their searches to identify primary iron manufacturing plants, little was done to keep their production in check. Thus, the Iron Act of 1750 was generally ignored by the colonists. Even the Sarum Iron Works, which had been identified by Sheriff Owen, continued to operate for decades with the Iron Act in place. Instead of restricting iron production in the colonies, the passing of the Iron Act led to a rising feeling of ill will and defiance against England – feelings which would evolve in the coming years to fuel the American Revolution.

After declaring independence in 1776, the colonies found themselves in need of weaponry and supplies. America called on the services of the Sarum iron mills to provide the Continental Army with high quality iron products for the war. Ironically, the very mill that England attempted to suppress through legislation was now used as a center for creating tools for the Revolutionary Army. In response, the Sarum Iron Works proudly produced at maximum capacity for the duration of the war, and proved to be an essential supplier in America’s fight for freedom.

After the Revolutionary War, things began to settle down at Sarum. Though John Taylor had passed away in 1756, Sarum Ironworks continued to operate for many decades under the management of his heirs. In 1836, the Wilcox family acquired the mills, which they renamed as the Glen Mills. Under the Wilcox family management, Glen Mills converted the standing Sarum Iron Works mills into paper mills. Now focused on producing money, the Glen Mills became internationally famous for its anti-counterfeiting measures. After enjoying over 50 years of success, the Glen Mills closed its plant in 1878, and in 1882 the area was sadly torn down to create the Glen Mills Railroad Station that still stands there today.

As a symbol of recognition and achievement, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission an historical marker there. Though the mills no longer stand at the site, this sign gives tribute to the area which once stood as a vital American plant as the Sarum and Glen Mills, and thousands of tourists visit this historical landmark each year.

Looking at the big picture, the simple invention of the iron rolling mill at Sarum Ironworks has had profound long term effects on manufacturing and societal issues. John Taylor’s creation of the first iron mill allowed colonists provided locals with cheap yet high quality metal products, and his ideas have evolved to provide manufacturing basis that is widely used in current industrial practices. More importantly, the Sarum Iron Mills played a pivotal role in the fight for freedom against England. Through the defiance of the 1750 Iron Act, Sarum helped to spread anti-British sentiment among the colonists and operated as an essential supplier for American soldiers in the Revolutionary War. While he may have started as a simple physician and business partner, John Taylor’s invention of the iron rolling mill has made an undeniable impact on the world we live in today.

Sources:

- Bining, Arthur Cecil. “Pennsylvania Iron Manufacture in the Eighteenth Century.” Publications of Pennsylvania Historical Commission Volume IV, 1938. Web. 2011 <http://www.clpdigital.org/jspui/bitstream/10493/146/1/Pennsylvania_Iron_....

- Bining, Arthur Cecil. Pennsylvania Iron Manufacture in the Eighteenth Century. 2nd Ed. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1973.

- ExplorePAHistory.com. U.S. Department of Education – Teaching American History Grant Program. Web. 18 Oct. 2010. <http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=898>.

- “Forges and Furnaces Collection 1727 - 1921.” The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Web. 11 Oct. 2010. <http://www.hsp.org/files/findingaid212forgesandfurnaces.pdf>.

- Frazer, Persifor. General Persifor Frazer, A Memoir. 1907. Archive.org. 2011 <http://www.archive.org/stream/persiforfrazersd021906fraz/persiforfrazers....

- Hillstrom, Kevin and Laurie Collier Hillstrom, eds. The Industrial Revolution in America. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006.

- Jenkins, Howard M. Pennsylvania, Colonial and Federal: a History, 1608-1903, Volume 3. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Historical Publishing Association, 1903.

- Jordan, John Woolf. A History of Delaware County, Pennsylvania, and Its People, Volume 1. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co., 1904.

- Scharf, J. Thomas, and Thompson Westcott. History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884. Philadelphia: L.H. Everts & Co., 1884.

- Shockey, Bonnie A. “Iron Works.” Allison-Antrim Museum Home Page. Nov. 2004. 18 Oct. 2010 <http://www.greencastlemuseum.org/Local_History/iron_works.htm>.

- Smith Jr., Richard P. “Two Hundred Years of Rolling on the Brandywine.” ArcelorMittal, Feb. 2010. <http://www.arcelormittal.com/plateinformation/documents/en/Inlandflats/T....

- Swank, James M. Introduction to a History of Ironmaking and Coal Mining in Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, 1878. Internet Archive. 2011 <http://www.archive.org/stream/castironmakingan020356mbp#page/n0/mode/2up>.

- Thomsom, Wilmer W. “Chester County and Its People.” Chicago and New York, The Union History Company, 1898. Web. <http://www.archive.org/stream/chestercountyits00thoms/chestercountyits00....