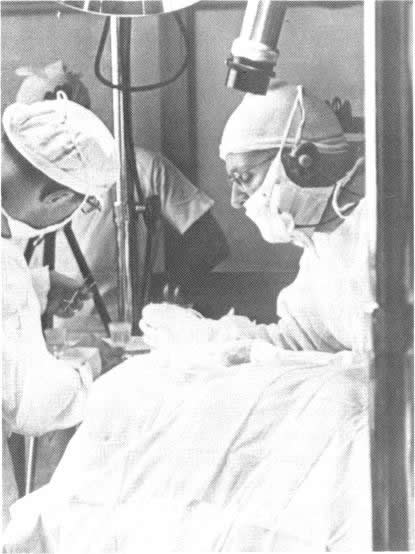

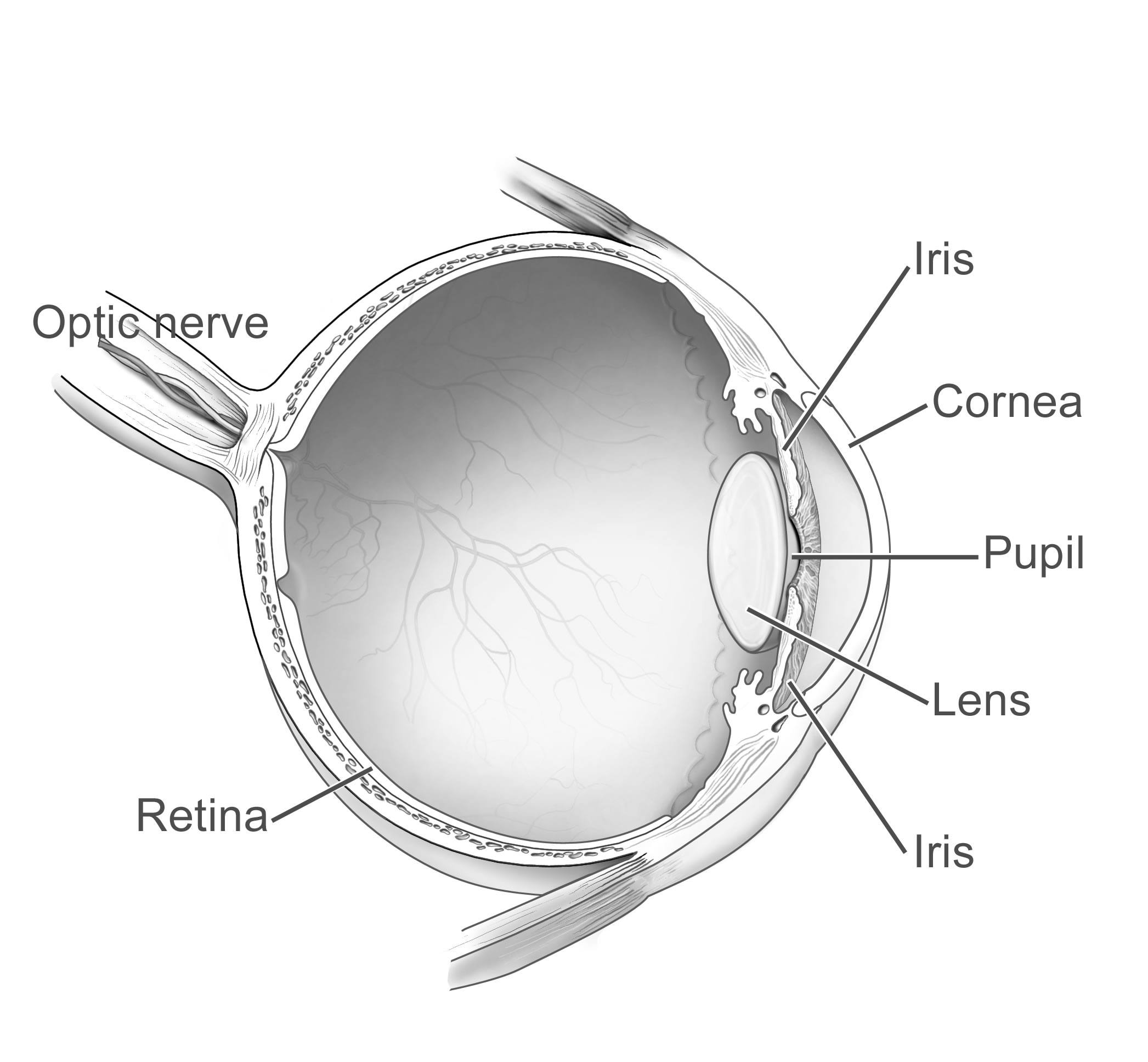

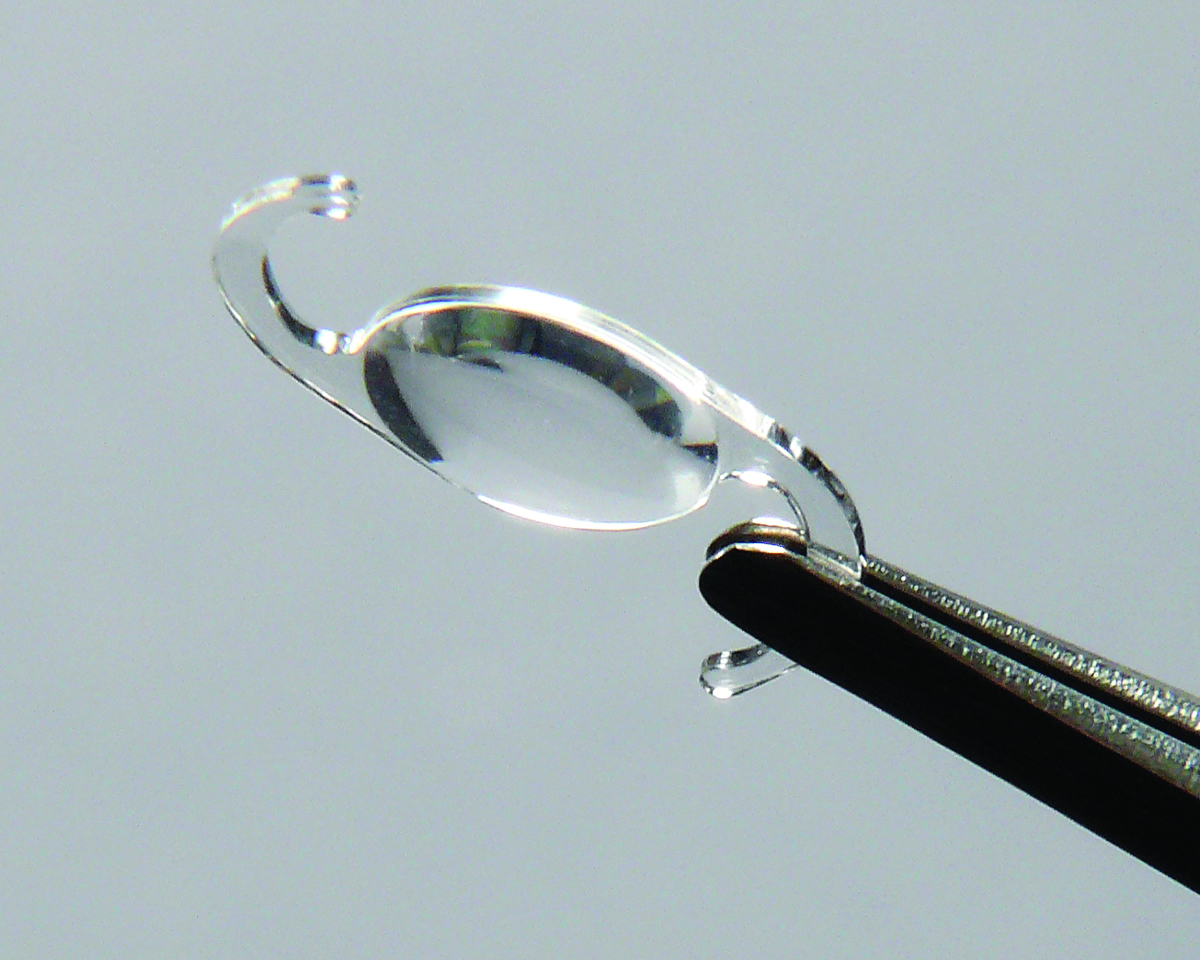

In a closed operating room, a 60-year-old bow-tied doctor bent curiously over a patient’s head, his mouth moving ever so slightly. With no high-tech equipment to assist him, the doctor had to be painstakingly careful as he used a thin, pointed instrument to make an incision in the topmost portion of the patient’s eye, the cornea. After a successful incision, a pair of precision forceps was used to extract a small, clouded, almost opaque lens from beneath the patient’s cornea. The doctor discarded the troublesome lens and retrieved an acrylic lens, no thicker than a fingernail, to replace the removed clouded lens. The process lasted no longer than an hour, and the patient was rolled off to recovery, the ability to see restored.

The year was 1952, and Dr. Warren S. Reese was the surgeon in the story. An ophthalmologist at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, Dr. Reese was the first American to successfully implant an acrylic intraocular lens (IOL) into a cataract patient. Today, cataract removal is the most frequently performed surgery in the United States with a success rate of nearly 98 percent.

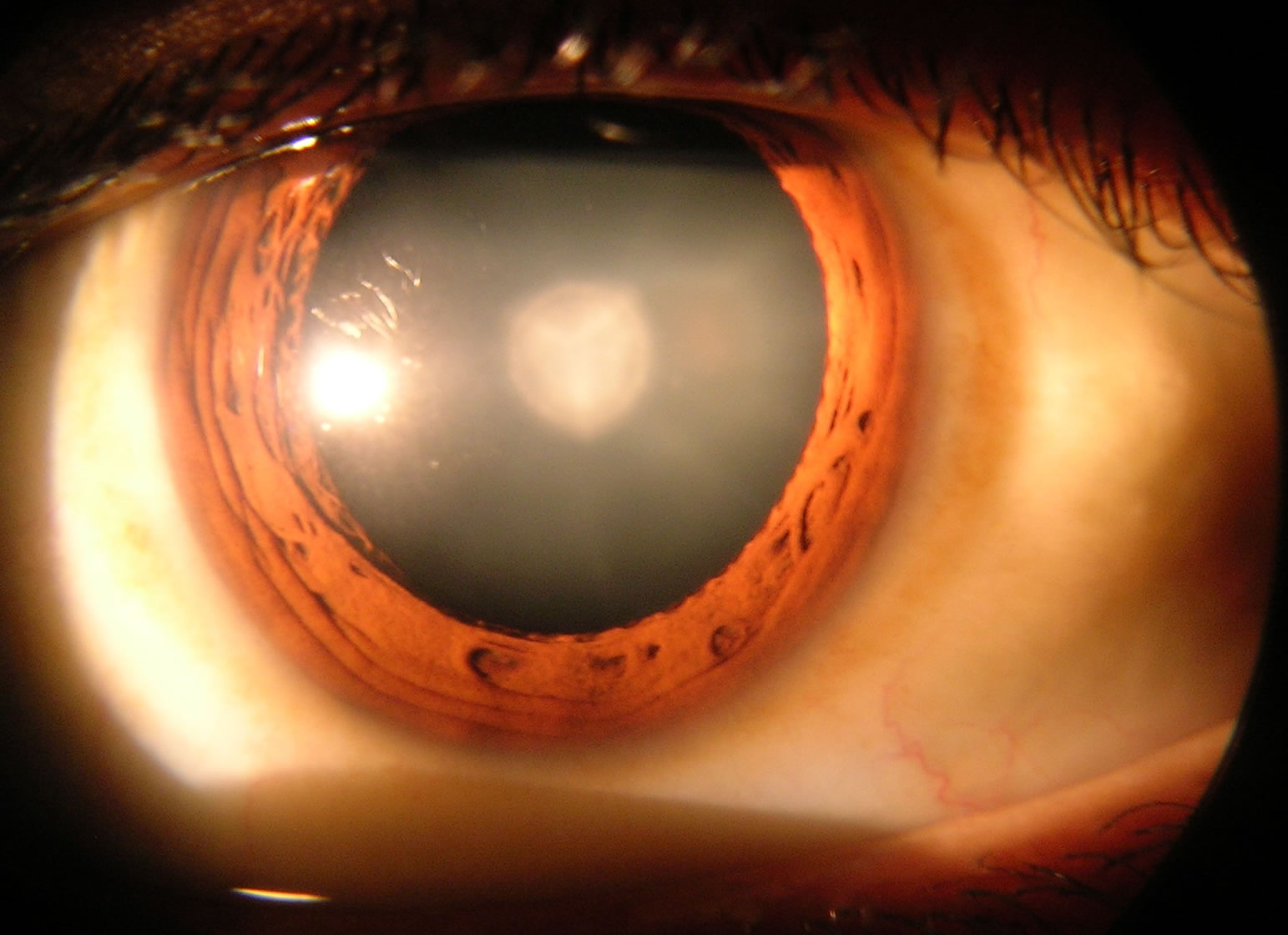

The word “cataract” is Latin in origin, stemming from the word cataracta, or “waterfall, portcullis, floodgate.” It was not until the middle of the 16th century that term cataract came to be used to identify a medical condition in which the lens of the eye becomes increasingly opaque, or clouded. Its Latin counterpart seems to perfectly describe its appearance and function. When a cataract forms, it almost looks as though it is a shallow pool of water within the eye. Not only that, but as it opacity progresses, it blocks light from entering the eye, serving as a sort of barrier, or portcullis, which steadily decreases a person’s vision.

Cataract surgery has existed for over 2,000 years. Evidence of a primitive form of cataract surgery was found in a Sanskrit manuscript dated 1 AD. The procedure described a technique called “couching” in which a tool was used to push the affected lens out of the field of vision of the patient. It was thought that the clouded lens would eventually disintegrate and vision would be fully restored. Of course, the majority of the time the cataract would return. It was not until the 18th century that the lens was physically removed.

French surgeon Jacques Daviel was the first to fully remove a cataract affected lens from a patient’s eye in 1750. The surgery required the doctor to make an incision in the patient’s eye without the luxury of anesthesia. Because of the discomfort, patients often rolled their eyes upward, causing difficulties for the surgeon.

Many of the attempted cataract removals, either by Daviel or other surgeons, were failures because of infection post-surgery or the inexperience of the surgeon. Because of these failures, cataract removal fell by the wayside and couching remained the preferred method for relieving patients of their affliction until the 20th century.

With the advancement of immobilizing and numbing medications, the removal of cataracts once again became feasible for ophthalmic surgeons. During World War II, the techniques for the removal of cataracts were perfected to the point that most surgeons thought no further improvement could be made to the procedure. That was until British ophthalmologist Dr. Harold Ridley, or Sir Harold after his elevation to knighthood in 2000, noticed that Perspex (a type of Plexiglas) does not cause reactions or infections when embedded into the human eye. This phenomenon was noticed during WWII when plane windshields, made from Perspex, would shatter and remnants would become embedded in a pilot’s eyes.

With this knowledge, Sir Harold Ridley used a plastic lens to replace the cataract affected lens during surgery. The doctor’s first attempt at inserting an IOL occurred in 1949 in a 45-year-old female patient. Unfortunately, there were complications from inadequate aftercare, and Sir Harold had to remove the implant. The ophthalmologist persisted and successfully reinserted a lens in the same patient a year later.

Sir Harold Ridley continued to perform this new type of cataract surgery but kept it private by not publishing his astonishingly positive results. His secrecy changed in 1951 when a patient accidentally scheduled a cataract removal with a Dr. Frederick Ridley. Dr. Ridley convinced the ophthalmologist to publish his results before someone else heard of his technique, and by 1952 Sir Harold Ridley was in Chicago at the American Association of Ophthalmologists conference to present his results. Sir Harold’s presentation in Chicago was criticized heavily by his American peers, with the exception of Dr. Warren S. Reese of Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia.

Dr. Warren S. Reese joined Wills Eye Hospital in 1920 where he was promoted to attending surgeon by 1939. As a pilot himself, Dr. Reese was inspired by Sir Harold Ridley’s innovation in the field of cataract removal and was eager to try the new procedure himself. The doctor was so eager, according to Dr. Eric Arnott, a fellow ophthalmologist and friend of both Sir Harold and Reese, that “[he] immediately flew back in his private plane to Philadelphia.” The very next day, on March 18, 1952, with the help of a fellow ophthalmologist, Dr. Turgut Hamdi, Dr. Reese became the first American to successfully complete an IOL implant surgery.

Eight months after Dr. Reese’s first operation the Chicago Daily Tribune reported, “Of 27 patients who have undergone this operation, only the first two had unsatisfactory results.” The number reported by the Tribune included both American and British patients. The two “unsatisfactory results” were the first two patients operated on by Sir Harold Ridley while he was still perfecting his revolutionary technique.

At the time of Sir Harold’s presentation in Chicago, Dr. Reese was a 60–year-old man. While Reese was able to perform and modify the “Ridley operation” for two years, in 1954 he became blind in one eye, and his years as a practicing ophthalmic surgeon came to an end. Even though he was unable to perform the surgeries, Dr. Reese still acted as an assistant to his colleague Dr. Turgut Hamdi.

Five years after his first operation, Dr. Reese co-wrote a paper with Dr. Hamdi aptly titled Five Years’ Experience with the Ridley Operation in which he reported on 115 operations he and Dr. Hamdi had completed. Even after five years of successful operations, many American ophthalmologists were still skeptical about the insertion of a foreign body into the eye. Reese recollected “few mature, experienced ophthalmic surgeons have attempted the Ridley operation, and so there is practically no literature on it and the various modifications that have been proposed.”

Even with the lack of literature on Sir Harold Ridley’s innovative implant technique, Dr. Reese was able to modify the original operation for the better. The revised technique used on a majority of Reese and Hamdi’s patients was “designed for simplicity, speed, control of hemorrhage and minimum trauma.” The new technique was very successful, allowing operations to be performed on patients in a wide age range, as well as on those who required superior vision for their career; these included a surgeon, a pilot, and a train conductor. Dr. Reese stated in his paper that “the commercial pilot astounded the Civil Aeronautic Examiners with his remarkable depth perception,” which shows the degree to which the Ridley operation, as well as Dr. Reese’s modifications, restored a patient’s vision.

Today, nearly six million implant operations are performed annually by ophthalmologic surgeons around the world. While the techniques for cataract removal have stayed shockingly similar since the 1960s, the types of lenses implanted into the patient’s eye continue to evolve. Patients have the advantage of multifocal, toric, blue-light filtering, or light-adjustable IOLs. All of which provide extraordinary vision correction post-cataract removal, depending upon the needs of the patient. Some progressive doctors, such as ophthalmologist, Dr. Jason Stahl of Durrie Vision, combine both refractive error correction and IOL implants to halt presbyopia, or aging of an eye’s lens, and to prevent potential cataract development. Stahl envisions a future where IOLs eventually come to replace refractive surgeries, as well as the use of eyeglasses stating, “We’re doing well with our current lenses, but I’m really excited to see what we’re going to be doing 10 years from now with, hopefully, truly accommodating lenses.”

Dr. Angela Chango, an optometrist with ten years of experience, and a graduate of the Pennsylvania College of Optometry, believes that without the advancements made by Sir Harold Ridley and Dr. Reese “the forefront of ophthalmic technology on preventing or treating cataracts and not all of these wonderful elective procedures we have now like Lasik and intraocular contact lenses would exist.”

Had it not been for Sir Harold Ridley and Dr. Reese’s persistence in perfecting the surgery, 22 million Americans with cataracts might be destined to wear thick glasses or suffer blindness for the rest of their lives. The revolutionary and ever-changing procedure is not just something that keeps cataracts at bay; it is the chance for a person to regain their sight. As French novelist Marcel Proust once said, “The real voyage of discovery consists of not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.”

Sources:

- Albert, Daniel M. and Diane D. Edwards. The History of Ophthalmology. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Science, Inc, 1996.

- Arnott, Eric J. A New Beginning in Sight. London: Royal Society of Medicine, 2007.

- “Cataract - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary.” Dictionary and Thesaurus - Merriam-Webster Online. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated, 2011. 2 Mar. 2011. <http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cataract>.

- Choyce, Peter. “One on One with Peter Choyce.” Interview. Ocular Surgery News. 1 Nov. 1999: n.pag. OSNSuperSite. 10 Oct. 2010 <http://www.osnsupersite.com/view.aspx?rid=14281>.

- “Interview with Dr. Angela Chango, OD.” E-mail interview. 7 Nov. 2010.

- “Marcel Proust Quotes.” Goodreads. Goodreads Inc, 2011. 3 Mar. 2011 <http://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/233619.Marcel_Proust>.

- Reese, Warren S., and Turgut N. Hamdi. “Five Years’ Experience with the Ridley Operation.” American Medical Association 58.3 (1957): 389-91.

- Segre, Liz. “Intraocular Cataract Lenses (IOLs): Premium | Aspheric | Toric.” Consumer Guide to Eyes, Eye Care and Vision Correction - LASIK, Contact Lenses and Eyeglasses. Mar. 2010. 12 Oct. 2010 <http://www.allaboutvision.com/conditions/iols.htm>.

- Tasma, William. “Warren S. Reese, M.D.” Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society 88 (1990): 13-15.

- “The Future of Refractive Surgery and Presbyopic IOLs with Jason Stahl, M.D.” Interview by Parag Majmudar. Opthalmology Web. Opthalmology Web, 2008. Feb. 2011. <http://www.ophthalmologyweb.com/Videos/26622-The-Future-of-Refractive-Su....

- Van Dellen, Dr. Theodore R. “How to Keep Well.” Chicago Daily Tribune 4 Nov. 1952: 14.