Home of Arnold Palmer. Birthplace of Fred (Mister) Rogers. Summer bastion of the Pittsburgh Steelers. Even the reputed home of the banana split. All describe, but fail to define a town that owes its identity and national recognition to one famous mainstay: Rolling Rock beer. While it wasn't the first to be brewed there, Rolling Rock is by far the most iconic and popular, and it has contributed in ways almost incomparable to any single entity to character of its home.

Founded in 1893, The Latrobe Brewing Company opened its doors in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, a small community of about 9,000 that sits at the foot of the Allegheny Mountains of Westmoreland County, about 40 miles southeast of Pittsburgh. Latrobe's first "brew masters" were, as assumed in local history, a group of Benedictine Monks who had originally populated the area, who founded St. Vincent College just a few miles south, and who, in turn, started the tradition of brewing in Latrobe. The brewery was run as an extension of the then growing Pittsburgh Brewing Company and enjoyed success until 1920 when operation was suspended and the 18th Amendment established Prohibition. Though alcohol production and sales in the United States were put on hold, it was not to be the end of the short-lived brewing era in Latrobe.

During Prohibition, four local brothers, Frank, Robert, Ralph, and Anthony, of the Tito family took a gamble and purchased the idle facility in hopes that Prohibition would soon be repealed. The venture paid off gloriously and in 1933, the Brewery was back in business. For six years, the Tito brothers brewed Latrobe Old German and Latrobe Pilsner varieties. It was then in 1939 that Rolling Rock officially got its introduction to the world.

Water, malt, rice, corn, hops, and brewer's yeast. The ingredients that comprise Rolling Rock are rather simple. And as promised on Rolling Rock's green, long neck bottles, "...from the mountain streams to you," the mountain water and rice which contribute to the extra-pale lager's distinctive flavor are all Latrobe. In fact the rather light-bodied beer has been said to change ever so slightly in taste from year to year due to the sediments that run off the hills into the mountain streams that feed the main brewing reservoir. That stream's bed filled with smooth stones is thought to be responsible for Rolling Rock's name. But, its bottles and the "mystery" painted on them is perhaps more famous than its taste.

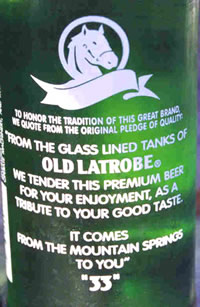

Rolling Rock, since its creation, has been bottled in distinctive green glass bottles with white painted lettering in both standard 12 oz. and the smaller 7 oz. "Pony Bottles". That white pony adorns the front of the bottle and on the back, the slogan "Rolling Rock. From the glass lined-tanks of Old Latrobe we tender this premium beer for your enjoyment, as a tribute to your good taste. It comes from the mountain springs to you. '33.'" The "33" is what has puzzled its loyal followers for years and the theories as to what it means are almost as numerous as the drinkers of the beer themselves. Conventional wisdom suggested it was a number for the printer indicating how many words were in the slogan that was somehow forgotten to be removed. But many, many others have sprung up since. There are 33 steps from the first floor to the second in the Latrobe Brewery. There are 33 letters in the list of ingredients. 1933 is the year Prohibition was repealed. There are supposedly 33 mountain springs that feed the brewing reservoir. It's even been suggested it has something to do with Groundhog's Day, the 33rd day of the year and a bit more than a tradition in western Pennsylvania. In the end, it turns out that even the brewery doesn't know, or at least they won't admit that they do.

Whether or not they purposely never offered an explanation or not, what they did do was make Rolling Rock their mainstay, and its sales supported the brewery for decades. Ironically, the beer's success was never a result of a concentrated marketing effort by the Tito family, contrary to the mass marketed world of high volume beverage production in America today. Well into the 1980s, the family never tried to promote Rolling Rock as a national brand, and their sales promotions were basic at best. In fact, the most common tactic employed was having Rolling Rock representatives simply buy rounds for the boys at local pubs and taverns. Yet, they constantly reinvested the profits back into the facility, expanding its production and capacity. Perhaps this is what gave Rolling Rock its homey feel or caused it to be embraced by mill and steel workers who shared pints after long days on the job. Rolling Rock became a Western Pennsylvania icon rather than a beer; its brand equity enviable and its drinkers' loyalty unshakable. Rolling Rock was as unmistakably Latrobe as the Steelers were unmistakably Pittsburgh in the 1970s. Unfortunately, the 1970s weren't as kind to the beer as they were to then four-time Super Bowl Champions.

Rolling Rock's production peaked in 1974 at 720,000 barrels on the 35th anniversary of the beer's birth. The lack of focus in marketing by the Tito's was eventually overcome by the mass marketing giants of the industry and new marketing and packaging techniques which they embraced. While it never was a truly national brand, much of the demand outside of southwestern Pennsylvania had shifted towards trendier beers, and sales fell accordingly. By 1985, the Tito family sold the business as production had dropped to about 450,000 barrels and two labor strikes had caused turmoil in the company.

Perhaps a testament to the mindset of the Western Pennsylvanian, Latrobe Brewery again was not to fail. In 1985, a buyout firm named the Sundor Group purchased the brewery and began to inject a much needed marketing budget into the dying brewery, hoping to sell it off for quick profit. However, Sundor Group had spread itself too thin financially and was forced to boost marketing efforts at the expense of capital expenditures. Awareness and accessibility increased, but quality suffered.

The relationship lasted only until 1987 when Labatt U.S.A. acquired the brewery. John Chappell, a brand manager from Labatt decided that the distinctive packaging and painted green glass bottles were Rolling Rock's strongest asset. Labatt launched a campaign emphasizing their uniqueness as well as the slogan that was painted on every bottle. Labatt's expertise in marketing and distribution revitalized Rolling Rock and brought its popularity to a national scale. The next fifteen years saw double digit growth, creation of the Rolling Rock Town Fair, a huge outdoor concert event that grew so quickly it was moved to Pittsburgh, and was the pinnacle of Rolling Rock's life in Latrobe. Unfortunately, time had run out for Latrobe's marriage to Rolling Rock.

National attention would focus on Latrobe when Labatt's sold its brands, but not its facility in the town, to InBev USA, the American branch of Belgian-based InBev SA, which eventually sold the brand to Anheuser Busch in May 2006. Anheuser Busch decided to move production to Newark, NJ shortly thereafter, shocking the citizens of Latrobe and costing hundreds of workers their jobs. Even Arnold Palmer, the town's most famous ambassador, would not comment on the move, citing too many strong feelings.

Western Pennsylvania is familiar with economic upheaval, especially in the last forty years, but the feelings Mr. Palmer acknowledged are a bit more personal, more nostalgic, more loyalty-driven, than when the mills closed in the 70s.

"Rolling Rock was the city," local business owner Roy Burk suggested.

Joyce Stern, another local restaurant owner claimed, "It's an icon. It's the identity of this town," shortly after news of the sale. The highest paying job in the city and the largest employer was uprooted, and workers were forced to find new jobs in 60 days. Perhaps the most telling of all were the vows to change life-long habits.

"A customer who drinks nothing but Rolling Rock came in and switched today to Coors Light," said Crissie Eagle, manager of a local establishment called Frank's Lounge. While Anheuser Busch is currently taking on the challenge of recent declining sales, they are experiencing a backlash in southwestern Pennsylvania.

In the immediate aftermath of the sale, more, similar sentiments were voiced. Interest groups were formed by beer enthusiasts and workers' families protesting the sale, lauding the beer, and hoping that it was not the end for Latrobe Brewery.

And, as seen in its past, indeed it was not. The Brewery was purchased and is currently owned by City Brewing Company of LaCrosse, Wisconsin. Along with help from a more than willing town and tax breaks from the Pennsylvania government, City Brewing has been able to reopen and revitalize the brewery. City Brewing contracted with the Boston Beer Company to brew Sam Adams brand beer there in 2008 and confirmed further production in 2009. In fact, Boston Beer has expanded production to some of its winter varieties, Sam Adams Oktoberfest, and has invested significantly in the expansion and modernization of the facility.

While Rolling Rock may never be produced in Latrobe again, and the mountain springs have been replaced by brick and mortar in Newark, NJ, the town itself lives on, a testament to the survival instinct of the area. Production is increasing at the brewing facilities. The Steelers and their fans still visit for training camp every year, frequenting the bars and small shops of Latrobe. The mountain springs still flow as free as ever, rolling their rocky bottom stones forward as the town moves forward. Rolling Rock may be lost from Latrobe, but its legacy is not forgotten, and neither is the promise of brewing in Latrobe.

Sources:

- Boselevic, Len. "State to help Latrobe brewer restart by May." Knight Ridder Business Tribune Business News 24 Jan. 2007, Washington ed.: 1.

- City Brewing Company. "Latrobe Brewery Questions." E-mail to the author. 12 Feb. 2009.

- Holl, John. "Latrobe's Fizzle Is Newark's Fizz." The New York Times 8 Aug. 2006, Late Edition ed., sec. 3.

- Hubbard, Jaimie. "Labatt rocks into U.S. with Latrobe brewery." The Financial Post [Toronto, Canada] 12 Oct. 1987, sec. 1: 7.

- Lash, Cindi. "Latrobe Lamenting Loss of Icon." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 20 May 2006, Business sec.: A1.

- "Latrobe Brewing Company -- Company History." Connecting Angel Investors and Entrepreneurs. 10 Mar. 2009 <http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/

Latrobe-Brewing-Company-Company-History.html>. - MacDonald, Bob, and The Globe Staff. "The mystery of Rolling Rock; Short Cuts/The Beer Facts." The Boston Globe 14 Jan. 1993, City ed., Calendar sec.: 6.

- Mervis, Scott. "Rolling Rockers Town Fair Takes Over Rural Westmoreland With Pie- Eating Contests And Chili Peppers." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 4 Aug. 2000, Region ed., Arts & Entertainment sec.: W1.

- Mortimer, C. M. "Boston Beer to buy Pa. brewery." Knight Ridder Business Tribune Business News 3 Aug. 2007, Washington ed.

- Mortimer, C. M. "Rolling Rock Sales Plummet in Pittsburgh." Knight Ridder Business Tribune Business News 22 June 2007, Washington ed.: 1.