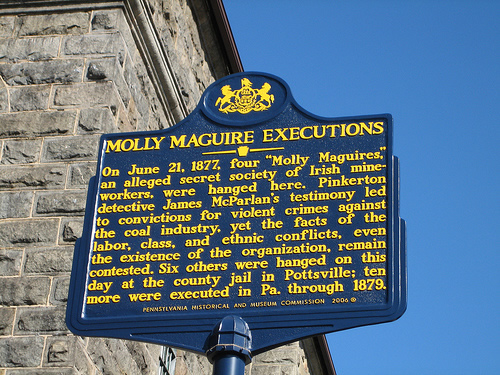

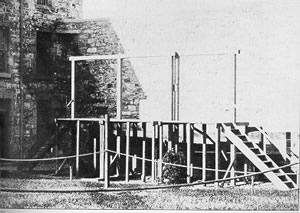

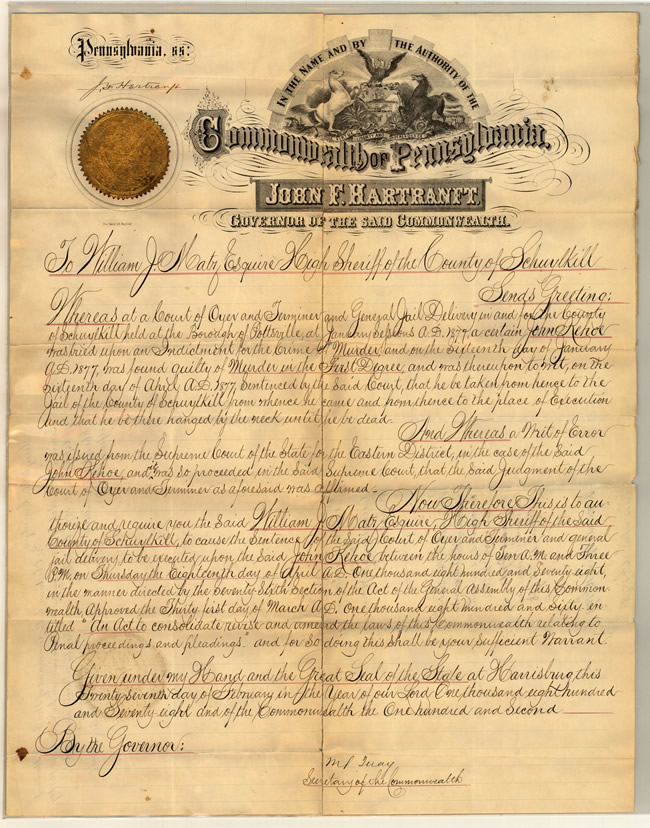

On June 21, 1877, twenty men linked to the secret organization called the “Molly Maguires” were hanged in the Carbon and Schuylkill county prisons for first degree murder. These men were sentenced to death by judges who were heavily influenced by powerful mining companies and the biased testimony of a spy, James McParlan. Today, these hangings have been recognized as unjustified, and in 1979 the state of Pennsylvania gave John Kehoe, the alleged king of the Molly Maguires, a full state pardon over a hundred years after his death. June 21, 1877, the sad day when twenty members of the Molly Maguires were hanged, has since been referred by the state of Pennsylvania as “Black Thursday.”

The Molly Maguires’ name can be traced back to early 19th century Ireland. Molly Maguire, an Irish widow, in the 1840s, protested against English landlords who tried to steal peoples land. She headed a group called the “Anti-landlord Agitators” who were best known for getting in bare knuckle fights with their landlords in order to maintain their land and their dignity. “Take that from a son of Molly Maguire!” was often heard after group members would deliver a beating. Eventually their violence gained notoriety across Ireland, and they later proudly called themselves the “Molly Maguires” after their leader.

During the mid-19th century, America saw a huge influx of Irish immigrants. Many of these immigrants moved to the anthracite coal regions of eastern Pennsylvania to find work, specifically in the mines located in Carbon, Schuylkill, and Lehigh Counties. The Irish moved to America hoping they would escape horrible working environments and the brutal tyranny of the English, as well as to find a better life for their families. They soon discovered that the conditions in America were not so different from the conditions in Ireland. They were subject to overwhelming ridicule and discrimination. When searching for work, they would see “Help Wanted” signs, but often followed by the words, “Irish need not apply.” When they were fortunate enough to find jobs, they were working in the most dangerous and horrendous conditions in 19th century America.

With almost no labor or mining laws, the coal mines were extremely dangerous and in decrepit condition. In 1864, the Workingmen’s Benevolent Association (WBA) was formed in Pennsylvania to help enforce appropriate and safer mining conditions. The WBA strictly forbade violence and opposed militancy. However, this organization catered more to its own interests than the needs of the workers. Due to this self-serving attitude and also due to prejudice that existed within the organization, the Irish decided to form their own group to protect their workers. This group was known as the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH). The AOH only allowed Irishmen or sons of Irishmen. They sought to provide fairness for the Irish working class and were willing to punish those who mistreated workers.

Many of the Irish immigrants who relocated to the Anthracite coal region of Pennsylvania originated from oppressed regions of Ireland where the Molly Maguries fought for human rights. It is believed that the Molly Maguires resurfaced in the Pennsylvania coal region in order to fight for the Irish coal miner’s rights, but no concrete evidence has ever been obtained to confirm their existence. However, most historians have since accepted their existence as fact.

The Molly Maguires was a secret group. Many believe the AOH was their cover or working name, which was recognized by the state as a legitimate organization. Once an Irishman had proven himself in the AOH, he could then be inducted into the Molly Maguires. When the AOH could not make changes through legislation, the Molly Maguires allegedly tried to make changes through force. However, despite the AOH and Molly Maguires fighting hard for better working conditions, little improvement was made. As a result, in 1875 they resorted to what became known as “The Long Strike.”

The Long Strike of 1875 was the first important open coal dispute in the anthracite coal region of Pennsylvania. Due to the nature of the Molly Maguires, it was also the scene for some of the most violent crimes in labor history. Both the unions and the coal companies were responsible for numerous violent acts during the strike including violent brawls, sabotage, and even coordinated murder. To combat the union violence, the coal authorities formed a police force, described in history books as the “Pennsylvania Cossacks,” whose sole purpose was to kill violent strikers. Eventually, the violence got out of hand and the coal companies needed to put a stop to the chaos. This is why James McParlan was recruited by the coal companies to infiltrate the AOH and provide enough incriminating evidence to bring them to trial.

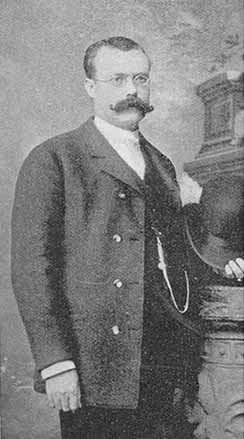

James McParlan was a native Irishman who worked for the Pinkerton Detective Agency, also known simply as the “Pinkertons.” The Pinkertons often sold their services to the mining and railroad industry. They were an organization that companies could hire as a private military in times of crisis. During The Long Strike, McParlan assumed the alias of James McKenna and infiltrated the AOH. He first became a member of the AOH in Schuylkill County by swearing he was a member of the Buffalo, New York chapter. From there he gradually worked his way deeper and deeper into the organization, eventually being initiated into the secret group of the Molly Maguires.

With the assistance of McParlan, the police were able to arrest over 60 men in 1875 accused of being linked to the Molly Maguires. These arrests made it possible to defeat the miners strike. Despite the strike ending, the mine owners wanted more. From 1875 to 1877 a series of trials were held in Pottsville, Pennsylvania to uncover alleged crimes committed by the Molly Maguires. Although the trials could not provide any evidence that the Molly Maguires actually existed, the media still referred to these men by that name. Since there was no evidence to link these men to the Molly Maguires, the men were tried as individuals. The trials resulted in 20 men being sentenced to hang. Emotions were so strongly against them that before they were executed, they were excommunicated from the Catholic Church and consequently denied a proper Christian burial.

During and after the trials, the local and national press had a field day at the Mollies expense. They compared the Molly Maguires to groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and stated, “floggings, lynchings and tar-and-feathers” were common practice for both groups. They demonized the Mollies, referring to them as “Black-riflemen,” portraying them as a gang of ruthless murderers. Very little truth ever came out of the media’s stories and these media tactics are now referred to as “yellow journalism.”

During the Molly Maguires trial there were numerous incidents of skeptical testimony that has now been recognized by the state of Pennsylvania as inconclusive evidence. It has been speculated that the witnesses were clearly refutable and the evidence was circumstantial at best. Even McParlan was accused of perjury during the trials, but he was never convicted. The court found 20 men to be guilty for the coordinated murder of John P. Jones, Ben F. Yost and several other mining officials, policeman, and supervisors that took place during The Long Strike. On June 21, 1877, these 20 men were hanged as punishment.

To date, official documentation that the Molly Maguires ever existed in America has never been produced, but their legend will not be forgotten. After the hangings, the coal miners and the Irish community regarded the Molly Maguires as heroes. They admired their courage and determination through one of the most difficult union movements ever recorded. The Molly Maguires are recorded as the first worker-only labor movement in American history.

Today, the Mollies are remembered through numerous mediums including a monument in Mahanoy City, a 1970 movie titled The Molly Maguires starring Sean Connery, and a known historical meeting place of the Mollies called The Wooden Keg Tavern, to name just a few. The Mollies have even been the inspiration for music. An Irish folk band called “The Dubliners” wrote a tale about their ordeal that sings, “Make way for the Molly Maguires. They’re drinkers, they’re liars, but they’re men. Make way for the Molly Maguires. You’ll never see the likes of them again.”

Sources:

- Godcharles, Frederick. “Molly Maguires.” Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. 8 Apr. 2009 <http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/events_that_sha... >.

- Kenny, Kevin. Making Sense of the Molly Maguires. New York: Oxford UP, 1998.

- “The Mollies Are Coming.” 8 Apr. 2009 <http://www.geecoders.com/MollyMaguires/>.

- “The Molly Maguires (1970).” Lehigh University. 8 Apr. 2009 <http://www.lehigh.edu/~ineng/paw/paw-history.htm>.

- O’Gara, Eileen. “The Molly Maguires.” The Molly Maguires. May 1998. Providence College. 8 Apr. 2009

- Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. "Molly Maguire" records at the Pennsylvania State Archives. 8 Apr. 2009 <http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt?open=512&objID=3162&&Page... >.