Following the American Revolution, the colonies faced not only the challenge of establishing a political foundation, but also the task of developing the services and institutions that colonists had customarily relied upon European nations to provide, including medical education and care. Prior to 1800, institutionalized medicine in the colonies was scarce, limited to the medical schools affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania, Columbia University, Harvard University, the College of Philadelphia, and Dartmouth College. The one-third of Philadelphia physicians who possessed formal medical education and training were discredited by those whose training consisted solely of countryside apprenticeships. One of these “regular” physicians, William Douglas, expressed the divide: “In general, the physical practice in our Colonies is so perniciously bad... it is better to let nature... take her course... than to trust the Honesty and Sagacity of the Practitioner.” While it was common for eighteenth-century physicians to engage in civic and political life, organizations of physicians, scientists, and academics, including the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, aimed to establish higher order and standards consistent with medicine as an exclusive career.

The College, the pioneer private professional medical association in America, encouraged scientific inquiry and dissemination of knowledge to the professional community through the publication of updated findings on diseases, treatments, and procedures. These publications reached a larger audience than the traditional method of passing down information from mentor to select mentees. This, coupled with the College’s historical medical collection and initiatives in educational standards and public health, modernized and expanded the American medical community as the young nation gravitated toward self-sufficiency.

A step toward the development of a new link between the public and professionals took place on January 2, 1787, when 24 prestigious physicians enacted a constitution formally establishing the College of Physicians of Philadelphia and its mission of “[advancing] the science of medicine, and thereby [lessening] human misery.” The founders included many accomplished Philadelphians, such as John Morgan, the founder of the first public American medical school in 1765, John Redman, one of the oldest physicians in Philadelphia, and Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and physician general of the United States military hospitals during the Revolution. Although Redman served as the first president of the College until 1805, Rush’s unwavering dedication to improving the practice of medicine and expanding medical knowledge distinguished him during the establishment of the College. Americans, including all but one of the College founders, frequently attended European medical schools such as the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, and then returned to the United States to practice. Rush believed America needed to improve its medical practices and scientific scholarship in order to match the eminence of European medical institutions.

As the largest city in the colonies from 1750 to 1800, Philadelphia was an appropriate place to begin. However, Rush hesitated about moving forward with his idea of a medical society before the restoration of stability in the post-Revolutionary colonies. He expressed his concerns in a November 15, 1783 letter to English physician and friend John Coakley Lettsom: “I approve of your plans for instituting a medical society in Philadelphia, and am not without hopes of seeing it carried into execution as soon as the minds of our literati are more perfectly detached from the [politics] that have swallowed up all the ingenuity . . . of our country.” While subsequent correspondences between the duo suggest that Lettsom’s persistent encouragement to establish the College irritated Rush, it sparked the transformation of an idea into reality. The founders met in October or November 1786 for their first of three meetings prior to the formal establishment of the College.

Rush’s influence continued to grow as he presented the objectives of the College on February 6, 1787. The College’s emphasis on extensive research beyond the treatment of disease reflected Rush’s adamancy that “there does not exist a disease in nature, that has not an antidote to it.” Its members would not only need to expand upon previous studies, but also pioneer investigations into illnesses that were supposedly unique to the United States at that time, including tooth decay and seasonal vomiting. The botanical garden Rush hoped to establish would provide the opportunity to experiment with various medicinal plants. The College would disseminate this revolutionary information through a scientific journal as well as a medical library and museum. Ultimately, the work of the College was intended to serve the public. Therefore, the College aimed to make suggestions on public health policies.

With many ambitious goals, the new organization immediately began working. On November 7, 1787, the College submitted its first temperance appeal to the Pennsylvania State Assembly. The report presented the adverse health effects of alcohol and proposed that the legislature adopt heavy taxes on liquor because the legislature served “as the guardians of the health and lives no less than of the liberties and morals of their constituents.” After being ignored, the College sent another appeal to the United States Congress on December 27, 1790, suggesting that alcohol not only affected the health of the individual but also “degrade[d] our species as intelligent beings.” Although their efforts failed once again, this persistence would prove to be vital in successfully influencing medical education legislation in the 1880s and 1890s.

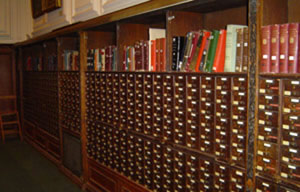

While the College struggled with legislation, its medical library thrived. Dr. Morgan made the first donation of 16 volumes in January 1788, catalyzing the donations of other members and the allocation of £50 to purchase foreign works. By 1791, the library containing manuscripts from European medical lectures, works of Aristotle and Hippocrates, as well as a copy of Giovanni Morgagni’s famous anatomy book De Sedibus et Causis Morborum began to overcrowd the College’s meeting room in the Academy of the University of Pennsylvania. Therefore, the College relocated to a new hall of the American Philosophical Society on South Fifth Street in December 1791 with hopes of expanding.

The rapid growth, however, was short-lived. The costs of furnishing the new hall resulted in admission and membership fee increases. With greater expenses, the College could no longer afford to purchase new works. The financial limitations and decreased literary donations resulted in a stagnant period until 1800 which the College had largely brought upon itself. The founders of the College comprised nearly half of the 50 traditionally-minded physicians among the 44,000 Philadelphia residents. This elite group intended to continue to exclude the upcoming generation of physicians. According to the College Constitution, only Philadelphian physicians older than 24 years of age would be considered for membership and were only admitted if three-fourths of the current members agreed. These restrictions reduced new membership and inherently lowered the College’s income and donation prospects. By limiting the size of the audience and potential benefits to the library, it was no surprise that the number of books borrowed dwindled down to only 25 volumes between 1792 and 1795. The College could also have boosted library growth by allowing members to borrow books more frequently than at the monthly meetings or by campaigning for donations. However, all attention diverted to a more urgent matter: the yellow fever epidemic of 1793.

The fever arrived in Philadelphia in August and claimed nearly 3,000 lives by the end of October. The mayor called upon the College on August 25 to develop a plan addressing the virulent disease. Within 24 hours, the College presented the mayor with suggestions, including limiting contact with the ill, marking the houses of infected individuals, creating a well-ventilated hospital, dressing warmly, and maintaining clean streets. These measures, printed immediately in newspapers throughout the Mid-Atlantic, were only temporary solutions until a common understanding of the fever was established among physicians.

Medical professionals split into two factions in the debate over the source and best treatment of the fever. The first, comprised of Rush and a few loyal followers, supported a domestic origin from pollution caused by decaying coffee remains. In his An Enquiry into the Origin of the Late Epidemic Fever in Philadelphia, Rush cites that the sailors from a coffee trade ship exhibited symptoms on July 22, the same day that the coffee began to smell and only five days before the first reported case. The age range of those afflicted by the fever in Philadelphia varied too much from that of the West Indies to have originated overseas. He claimed that his idea was scientifically based, as several doctors had previously published on rotting vegetables as a disease-causing agent.

The second faction, comprised of the majority of the College members, supported a foreign origin via trade ships from the West Indies. The views of this group heavily reflected the points presented in the 1793 response to Rush’s Enquiry by Mathew Carey, a Philadelphia publisher known for his fervent patriotic works demonstrating concern for his fellow Americans and his 1794 history of the yellow fever. He contended that the fever had to be imported since several foreigners ill with the fever arrived during the summer and perished during their visit. Such foreigners included a captain from the West Indies who arrived in late July presenting the symptoms characteristic to the Philadelphia fever. They found several scientific works conflicting with Rush’s evidence and literature by proclaimed experts stating that the behavior of the fever in the West Indies was too irregular to make conclusions by comparison.

Letters attacking the safety of Rush’s treatments first appeared in September in Philadelphia newspapers, spreading throughout the Mid-Atlantic as virulently as the fever. Rush adamantly countered his critics who dubbed his methods as “[contributions] to the depopulation of the earth” with claims that four-fifths of his patients treated with purging fully recovered. In his public October 1793 response to Dr. John Rodgers of New York, Rush argued: “The mistakes of some of my brethren have not ended here . . . Some of them blend wine, bark, and laudanure with [sparing bleeding]. They might as well throw water and oil at the same time upon the fire in order to extinguish it.” According to Rush, his closed-minded opponents failed to fulfill their duty to their patients by choosing common, ineffective elixirs over controversial but effective treatments. By the time the fever ended in November, Rush could no longer endure the “inveterate malice” toward his well-intended actions. He resigned from the College on November 5, 1793, donating to the library a copy of the works of his idol Dr. Thomas Sydenham, works which embodied Rush’s beliefs in “almost every page.”

With the departure of the man who had provided the College with much energy, the progress of the College slowed. The preoccupation with the epidemic caused the first issue of the College’s scientific journal Transactions to gain little domestic or international attention. The College advised the Board of Health during the epidemics of 1794 and 1799 and endorsed small pox vaccination in 1803, but it was otherwise stagnant as attendance and publication plummeted.

Revival and modernization of the College occurred in 1818 as age of the original founders ended. On March 4, Dr. Lyman Spalding of the New York Medical Society sent to the College a plan to compile a national pharmacopoeia, a centralized and standardized catalogue of American medicines, with the hopes of achieving the same esteem as the European pharmacopoeias widely consulted by American physicians. The two organizations pulled on the interest obtained by the College in 1789 when it first surveyed physicians for contributions to the pharmacopeia, establishing four conventions across the United States to discuss the anthology. The College hosted the convention for members of professional medical organizations in the middle district on June 1, 1819. The content chosen by the middle district nearly matched the final version agreed upon by the delegates at the national pharmacopoeia convention on January 1, 1820 in Washington, D.C.

The College was rewarded for its initiative with a joint copyright of the pharmacopoeia during its first publication in December 1820. The College continued to take an active role in the decennial revisions of the compilation as host of the convention from 1830-1870. In particular, the College earned much of the credit for the revision of 1830, seeking assistance from all its fellows and supporting revisions, corrections, and additions with the experiments of pharmacist D. B. Smith who was hired by the College Pharmacopoeia Committee. The exemplary contribution of the College inspired George Bacon Wood and Franklin Bache, both drafters of the 1830 revision, to publish the Dispensatory of the United States in 1833. According to the preface of the Dispensatory, the collection “embraces whatever is useful in European pharmacy” while “represent[ing] the art as it exists in this country and giv[ing] instruction adapted to our particular wants.” By further explaining the history, uses, ingredients, and preparation of the medicines presented in the Pharmacopoeia of the United States, the Dispensatory worked to establish the merit of American medicine, pulling it out from the shadow of its European counterpart in a professional and respectable manner. These two works by College fellows worked in tandem, with the latter undergoing a revision with each update of the first. Both the Pharmacopoeia and Dispensatory were associated with the College’s growing medical acclaim nationally and internationally.

The College’s literary presence began to flourish not only with publications, but also with a growing library collection. After more than three decades of neglect, the 291-volume collection housed in a single bookcase needed serious repair. Without $15,000 to build a new hall, the College relocated to the Mercantile Library in 1845. The inviting new space for the library sparked interest in fellows to donate hundreds of volumes and landed the College the entire collection of the Philadelphia Medical Society by the end of 1846.

The rapid expansion of the library combined with Issac Parrish’s small but growing collection for the pathological museum inevitably posed the need for a space of its own. The College set up a building fund in 1850, but fellows enthusiastically contributed only after Wood agreed to donate $5,000 when the fund reached $25,000. As the building fund grew, Thomas Dent Mütter, a renowned surgical professor of Jefferson Medical College, responded in 1856 to Parrish’s endeavors by agreeing to donate his 1,700-item pathological collection. He supplemented his gift with $30,000 to fund a curator and lecturers to educate both professionals and the public. His only requirement was that the home of his specimens be fireproof. The opportunity, which set the foundation for the College’s current 20,000-specimen Mütter Museum collection, was too great to turn down.

In 1863, the College’s made its monumental move to the fireproof building located on Thirteenth and Locust Streets. The new building garnered attention from medical professionals and sparked a surge in support for the library. Book donations, such as the 2,500-item one by Philadelphia physician Samuel Lewis, aided the College in its endeavor to create a comprehensive collection of medical history and practical knowledge. Generous donations used to purchase foreign journals and to staff the library helped the library to grow to an impressive 38,160 volumes and 16,026 pamphlets by 1886. The vast resources of the library reached an audience beyond Philadelphia through its interlibrary loan system.

After emphasizing the prestige of the College’s ownership of the oldest medical collection in his commemorative address of the centennial celebration on January 3, 1887, President S. Weir Mitchell continued to push for advances in healthcare quality. As a neurologist internationally renowned for his “rest cure” for all nervous ailments published in 1873, he believed that the College’s “largest office should be that of incessant watchfulness of all public interests in which questions of health are concerned.” He began his mission as a fellow in 1882 when he suggested the Directory for Nurses, a register of skilled nurses who were accessible to physicians at all hours. The disclosure of each nurse’s qualifications and references boosted the credibility of the Directory nationally, inspiring other organizations, including the Cincinnati Hospital, to enact similar systems. The 1,155 requests for nurses in 1886 exemplified the high standard to which College-endorsed nurses were held. The College benefited not only in fame, but in fortune since the fees collected for the service provided additional funding for library initiatives.

Mitchell was pleased with the success of the support system the College had created, but knew the impact of the Directory was limited by the preparedness of physicians, the perceived directors of the medical profession. Rush had asked in an 1813 letter to the trustees of the University of Pennsylvania, “Would you cross the ocean in a ship built by a carpenter who had heard lectures only upon shipbuilding for two years without ever having handled an ax or hammer?” Mitchell’s answer: no. The College revived the goal of ensuring that physicians possessed both factual knowledge and practical skills in 1843 by establishing a Code of Ethics. This code was adopted by the American Medical Association, which has missions of advancing medicine and public health similar to the College, at its founding in 1847. The legalization of educational dissections in 1883 and establishment of a State Board of Medical Examiners and Licensers in 1891 through direct influence by the College further distinguished the College as a progressive organization in the standardization and improvement of medical practice and training.

These successes driven by Mitchell, combined with his advocacy for the establishment of a federal Department of Public Health and Preventative Medicine, propelled the College to new acclaim in what became known as the “Mitchell Era.” The Mitchell Era from 1886 to 1914 came nearly 70 years after the 1817 death of Adam Kuhn, the last of the original founders, marking a significant transformation into a more inclusive organization. The 1886 decision to amend the College constitution and open membership to physicians within a 30-mile radius not only more than doubled membership in 20 years, but also infused life back into the College’s publications and outreach initiatives.

The growing recognition of the College was appropriately accompanied by the building of a stunning new hall and its current home on Twenty-Second and Ludlow Streets in 1909. The nearly $300,000 project, first initiated by Mitchell, created inviting new spaces to boost public involvement and education. Mitchell’s lecture on the discovery of blood circulation in 1910 marked the start of the series of well-attended free public lectures entitled “Great Doctors and Achievements in Medical Research.” Although the frequency of these lectures dwindled as the planning became increasingly time consuming, the unceasing focus on the new library during subsequent decades provided the opportunity for public engagement. The $50,000 donation by philanthropist and steel industry entrepreneur Andrew Carnegie in 1903 for a new library to bring together the public and professionals set the foundation for motivation that sustained this magnificent part of the College through financial troubles during World War II. College president T. Grier Miller’s adamant campaign for funds to expand the library’s stacks and reading rooms in 1949 and President Jonathan E. Rhoads’ ambitious 10-year plan to raise $1 million in 1958 propelled the College to new heights. By 1967, the library of the College of Physicians was part of the Regional Library System, lending 27,000 volumes per year to 300 different libraries across 33 states and reaching farther than its members imagined in 1787.

The success of the library was accompanied by a surge in public interest in the Mütter Museum at the end of the twentieth century. The enthusiasm of Gretchen Worden, the late curator and director of the museum, for sharing the “terrifying beauty” of the medical specimens radiated through her dedication to publicizing the museum. Her three appearances on The David Letterman Show, national and international lectures on the museum, and calendars and book released in 2002 containing photographs of the collection boosted attendance from several hundred visitors annually at the start of her tenure 1982 to 62,000 at the time of her death in 2004. Attracting more more than 105,000 visitors in 2008, the Mütter Museum is no longer solely a supplement to the historical library for the medical community but an institution that truly captures the public outreach missions of the College.

More than two centuries after its founding, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia remains a private medical society dedicated to public health, scholarship, and education. Its diverse body of 1,500 elected fellows includes physicians, public health advocates, academics, civic leaders, and other medical-related professionals from around the country. They take part in the College’s Sections on Public Health, Medical History, and Medicine and the Arts, hosting free forums and lectures for the public and medical community on current health topics. Such events have included a speech by Ronald Reagan on AIDS in 1987 and forums on the inequities of healthcare reform, revolutionary cancer diagnostics, and the H1N1 virus in 2009. The College strives to influence the lives of people of all ages and professions through its free online health information service, public garden of more than 50 medicinal herbs, and engaging “Mütter lessons” for children and Mütter Museum exhibits. The College continues to encourage curiosity and scholarship through public access to its 250,000-book historical medical library. Many scholars, who made nearly 300 research visits during the 2008-2009 fiscal year, have received travel grants to utilize the rich resources of the largest independent medical history research library in the United States.

The transformation of the College of Physicians from an idea into the nationally and internationally respected organization it is today is remarkable. The determination, dedication, and innovation of its fellows to advance medicine metamorphosed the medical profession from a small, local operation into the expansive, institutionalized one it is today. The incredible advances of knowledge, technology, education, and expectations of medicine since the founding of the College have made some of the discussions and debates among the historical members obsolete now. Yet, the original motto of the College still thrives: “Not for oneself, but for all.”

Sources:

- “An Account of the Origin, Symptoms, and Treatment of the Epidemic Fever, which Now Prevails in the City of Philadelphia, in a Letter, from Dr. Benjamin Rush to Dr. John Rodgers.” Federal Gazette. 7 Oct. 1793: 2.

- Bell, Whitfield J. “The Fielding H. Garrison Lecture: A Portrait of the Colonial Physician.” The Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 44 (Nov./Dec. 1970): 497-517.

- _____________. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia: A Bicentennial History. Canton, MA: Science History Publications, 1987.

- Biddle, Louis Alexander. A Memorial Containing Travels Through Life or Sundry Incidents in the Life of Dr. Benjamin Rush written by himself also Extracts from His Commonplace Book. Philadelphia: Ivy Leaf, 1905.

- Bradsher, Earl Lockridge. Mathew Carey, Editor, Author, and Publisher: A Study in American Literary Development. New York: Columbia UP, 1912.

- Carey, Mathew. Observations on Dr. Rush’s Enquiry into the Origin of the Late Epidemic Fever in Philadelphia. 1793.

- “Detailed History of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.” The College of Physicians of Philadelphia: The Birthplace of American Medicine. 2005. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. 20 Oct. 2009 <http://www.collphyphil.org/erics/cpphistory.htm>.

- Dhody, Anna. E-mail interview. 9 Nov 2009.

- “Directory of History of Medicine Collections.” United States National Library of Medicine. 19 May 2009. United States National Institutes of Health. 1 Dec. 2009 <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/directory/024.html>.

- Earnest, E. S. Weir Mitchell: Novelist and Physician. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1950.

- “Form of the Constitution of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.” The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. 2 Jan. 1787.

- Garrison, Fielding H. History of Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1913.

- Goodman, Nathan G. Benjamin Rush: Physician and Citizen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1934.

- Horrocks, Thomas A. “The College of Physicians of Philadelphia: ‘Not for Oneself, but for All.’” Pennsylvania Heritage. 13 (Winter 1987): 32-37.

- Mitchell, S. Weir. “Centennial Anniversary of the Institution of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia: Commemorative Address.” 3 Jan. 1887. Rpt. in Medical News. 8 Jan. 1887: 39-35.

- “In Memoriam: Gretchen Worden.” College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Aug. 2004. 3 Dec. 2009 <http://www.collphyphil.org/gw.htm>.

- “Open Physicians’ College to Public.” Philadelphia Inquirer. 6 Feb. 1910: 3.

- “Our History.” American Medical Association. 20 Nov. 2009. 28 Nov. 2009 <http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/our-history.shtml>.

- “Remembering Gretchen Worden.” Fresh Air. Narr. Mark Hochberg. WHYY, Philadelphia, 6 Aug. 2004.

- Ruschenberger, W.S.W. “An Account of the Institution of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.” Transactions of the College of Physicians. 1887: 1-175.

- Rush, Benjamin. “A Discourse Delivered Before the College of Physicians of Philadelphia on the Objects of their Institution.” Transactions of the College of Physicians. 1793.

- ___________. An Enquiry into the Origin of the Late Epidemic Fever in Philadelphia in a Letter to Dr. John Redman. 5 Nov. 1793.

- ___________. “Letter to John Redman.” 5 Nov. 1793. Rpt. in Letters of Benjamin Rush. Ed. L. H. Butterfield. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951. 740.

- ___________. “Letter to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania.” 1 Mar. 1813. Rpt. in Letters of Benjamin Rush. Ed. L. H. Butterfield. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951. 1184-85.

- Shryock, Richard Harrison. “The Medical Reputation of Benjamin Rush: Contrasts Over Two Centuries.” The Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 45 (Nov./Dec. 1971): 507-552.

- Stille, Alfred. Reminiscences of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia: An Address at its Centennial Celebration. 4 Jan. 1887.

- “The Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.” Medical Times. 15 June 1871: 338-42.

- Wood, George Bacon, and Franklin Bache. The Dispensatory of the United States of America. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1820.