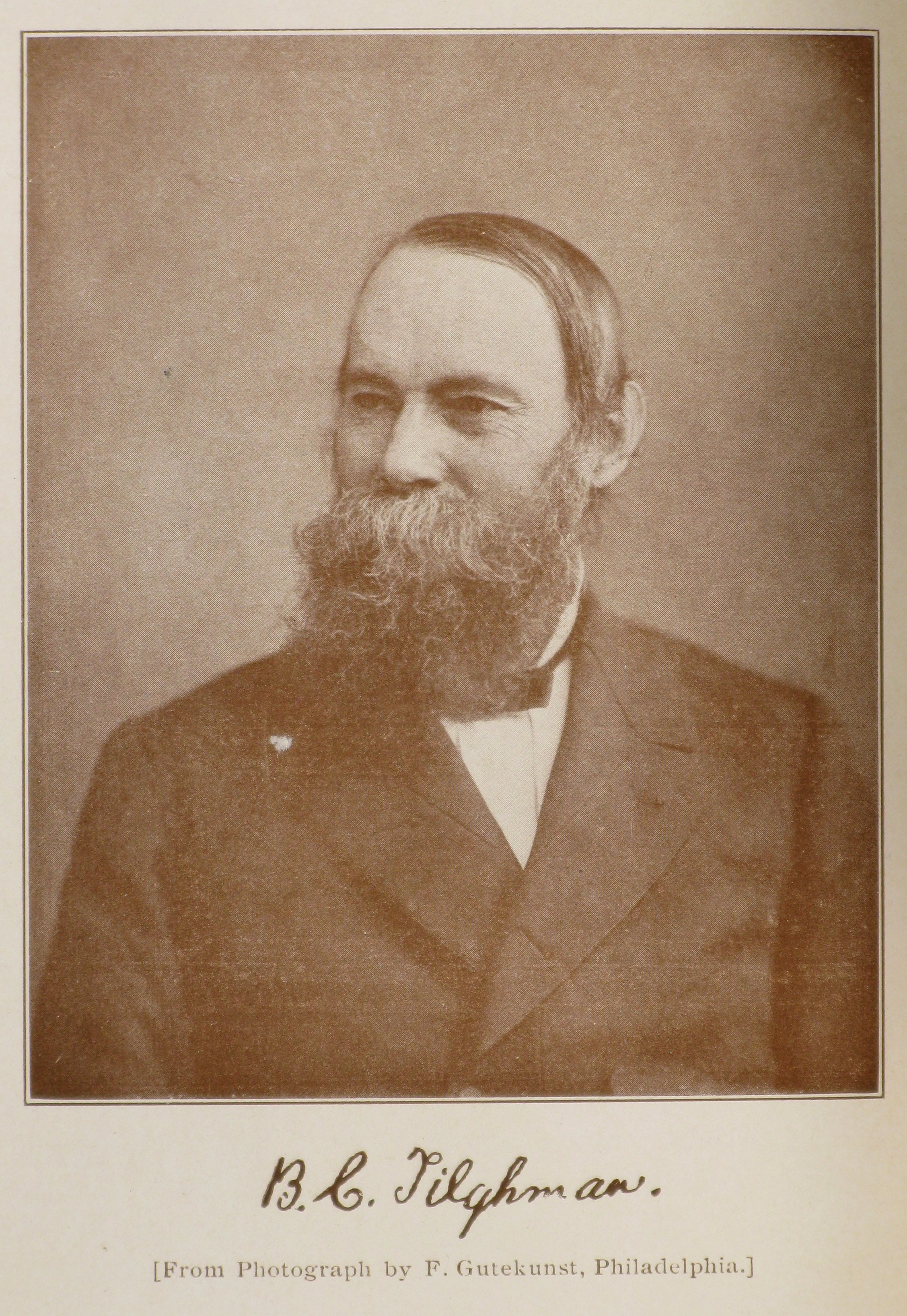

When viewing the artwork to the right one may think, “Wow, that glass has a beautiful engraving on it.” Rarely are people informed of the process used to create such beautiful pieces of art. Interestingly, the same process used to engrave this glass can be used to chisel stone and clean the hulls of ships before painting. The aforementioned process was invented in the late 1800’s by Mr. Benjamin Chew Tilghman, a soldier, inventor, and manufacturer.

Benjamin Chew Tilghman was born in Philadelphia on October 26, 1821. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania and obtained his B.A. in 1839, soon followed by a law degree and admission to the Pennsylvania Bar. However, this course did not please an 18-year-old Benjamin Tilghman. Instead of pursuing law as his father wished, he joined his brother Richard in a life of business, inventing, and manufacturing. His life was spent furthering the commercial success of his brother until the outbreak of the Civil War. In April 1861 Tilghman joined the Twenty-sixth Regiment of the Pennsylvania Volunteers and his life took an interesting turn.

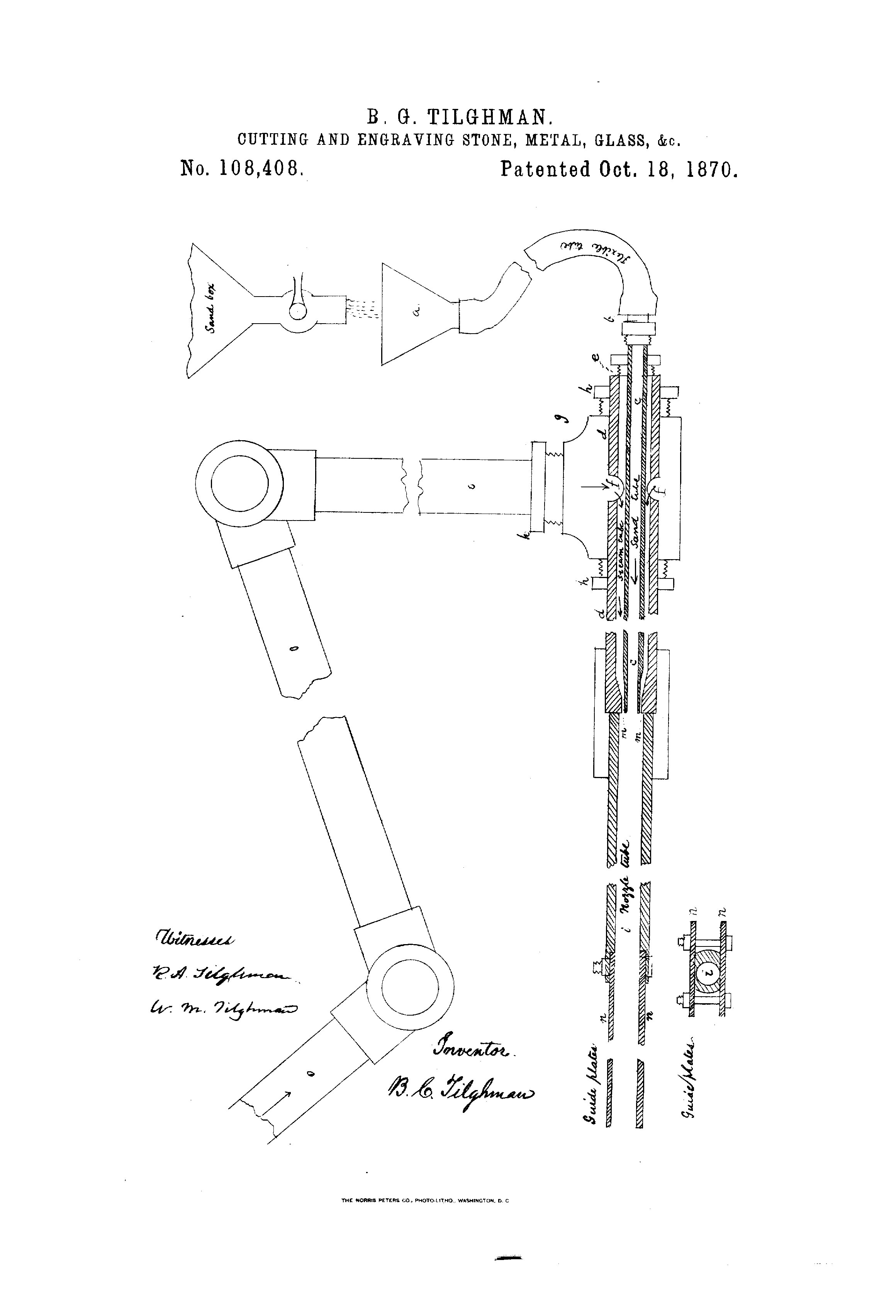

While in the army, he quickly climbed the ranks from company captain to regimental commander. All the while, he kept himself on the lookout for possibilities for new inventions. On a routine patrol in during the war, Mr. Tilghman observed something everyone has noticed at least once in their life: the corrosion on the outside of really old windows. The windows gain a rough appearance. If something, like bars, has been placed in front of them, one can actually see the shape of the bars etched into the window. He began to wonder whether this random occurrence in nature could be done purposefully. Eventually, General Tilghman became sure he could replicate this natural process and in 1870 he obtained U.S. Patent 108,408 for “Cutting and Engraving Stone, Metal, Glass, Etc.” a process that would become known as sandblasting.

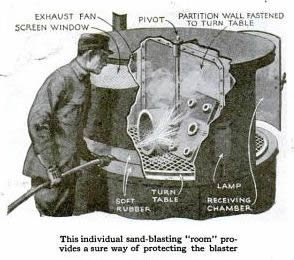

Once Tilghman’s patent was issued, he began extensive testing of his exciting new invention. He used the quartz in sand as the corrosive element in his design and a pressure jet of various fluids, including air, steam, and water, to carry it. In 1897, The Chicago Eagle ran an article titled “The Sand-Blast” whichstates that Mr. Tilghman “fitted up a very simple air-blast, producing but a few ounces of pressure, and by means of a concentric jet of glass this air was made to drive the sand against the object to be cut.” He later learned that the increases in pressure would increase the depth of the cut drastically. Soon after Tilghman discovered something even more interesting about his developing process; while the quartz sand could cut through materials much harder than itself, it would not cut through soft yielding substances, including human flesh. “The Sand-Blast” goes on to say that “The workmen can hold their hands under the blast and receive no injury, by simply wrapping their finger nails in little pieces of soft cloth.”

Once his invention was commercialized, others began to improve upon the process. Jeremiah E. Mathewson, for example, contributed a new device that improved the accuracy of the steam and sand stream while also collecting excess sand in a basin so it could be reused.

The modern day sandblaster varies enormously in size as well as uses. When ships come into port their hulls are cleaned using sandblasters. If homeowners want to repaint the side of their house, they need not spend countless hours scraping the paint off manually. Instead, they can rent a sandblaster from a home improvement store and turn a week-long project into a day-long one. Outside industry the process is used to engrave art on hard surfaces such as glass (as seen above), stone, and even wood. This brief list of the varying uses of sandblasting only scratches the surface (no pun intended!) of its effect on industry.

In addition to its plethora of uses, sandblasting has helped spawn an entirely different sub-process, shot peening. When discussing the degree of difficulty in modeling the surfaces of metals, Swiss physicist Wolfgang Pauli used to say, “God made the bulk; the surface was invented by the devil.” Those devilish surfaces proved hard to modify with the hammers and other tools of metalworking, partly inspiring the development of shot peening in the 1930s in Germany and the United States. Shot Peening is a surface process that uses nearly the same technology as sandblasting to produce very different results. The process uses larger spheres to bombard the exterior of a component and release tension in the surface of metals that are cast. Before this process it was reasonable to replace components that experienced varying forces yearly. Now the same components can be replaced every 10 years, or not at all.

As early as 1872, we begin to see articles about the new process know as sandblasting. In a Popular Science article “Little Grains of Sand” sandblasting begins its trek into mainstream use. Popular Science runs another article on sandblasting in 1912, this time referring to new innovations to protect workers from the noxious fumes created when cutting metal. Unfortunately, earlier versions of the process had their draw backs.

In July 1903, The Washington Times ran an article that stated “[...] and now the sandstone columns of the eastern portico of the Treasury are “disintegrating.” It isn’t too many months ago that they were so filthy with accumulated dirt of decades that they had to be “Sand-blasted.” While the process is excellent for cleaning and engraving hard materials, relatively soft materials like sandstone can easily form cracks if the pressure is too high while they are cleaned. This minor setback may have made people question the credibility of the process, but in no way did it detract from its usefulness.

George Iles, an industrial biographer and a contributor to Popular Science, wrote admiringly of Tilghman, declaring:

His independence and vigor of mind brought him to ideas wholly original, and his competency of fortune enabled him to develop these ideas with unflagging ardor throughout a long life. He had the prime impulse indispensible to any great success whatever—an intense interest in his work.

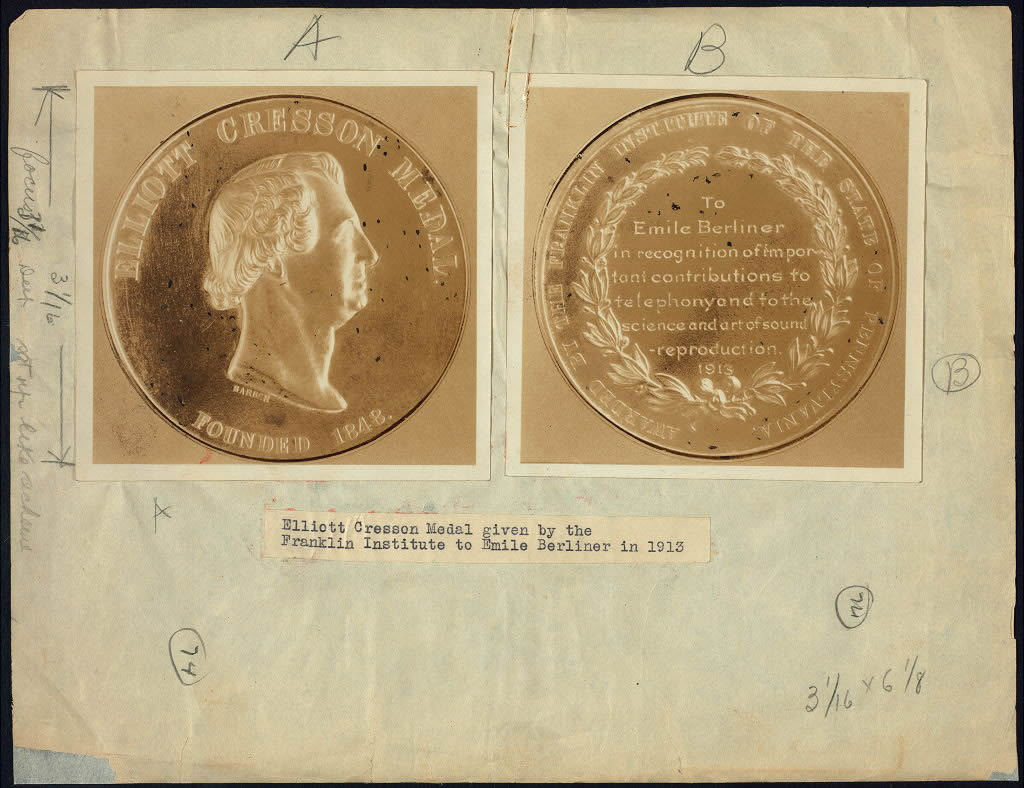

General Tilghman was also a recipient of the Elliott Cresson Medal. The prestigious award has been given by the Franklin Institute since 1875 “for the invention or improvement of some useful machine, for some new process or combination of materials in manufactures, or for ingenuity skill or perfection in workmanship.” In addition his process has been hailed as “industry transforming” by Charles W. Carey, a specialist in industrial history.

Nowadays society takes the process for granted. The paint that is applied so carefully to houses, cars, and boats, would need to be stripped by hand and repainted much more often without this “industry transforming” process. The Sobe and Arizona Iced Tea bottles we drink from do not come out of the blast furnace with the insignias etched into them. The art that inspires us could not be produced for the middle class before mechanized engraving became possible. People could not afford to pay someone to chisel all day long and support their family. Whether you look at the hand held sandblaster you can currently buy online and have shipped to you tomorrow, or the Hoffman Blast II line of blast rooms that could double as a garage you have to admit that the process of sandblasting has come a long way since its inception by Benjamin C. Tilghman.

The Center would like to thank Warwick Pascoe of Clearlight Designs for his help illustrating this article.

Sources:

- Cardon, Michel. “The Devil and the Surfaces.” The Shot Peener (Summer 2006): 38.

- Carey, Charles W. “Tilghman, Benjamin Chew and Richard Albert Tilghman.” American Inventors, Entrepreneurs, and Business Visionaries. New York: Facts on File, 2002. 342-3.

- Iles, George. Leading American Inventors. New York City: H. Holt and, 1912.

- “Little Grains of Sand.” Popular Science Feb. 1919: 64.

- “Making Things Easier for the Sand-Blaster.” Popular Science Dec. 1918: 76.

- Mathewson, Jeremiah. Sand-Blast Process. Jeremiah Mathewson, assignee. Patent 321512. 10 Nov. 1884.

- Pascoe, Warwick. Modern Contemporary Sandblasted Glass Art. Photograph. Byron Bay, Australia. Clearlight Designs. Clearlight Designs, 1 Aug. 2009. 14 Oct. 2010 <http://www.clearlightdesigns.com.au/>.

- “The Sand-Blast.” Chicago Eagle 8 May 1897: 2.

- Tilghman, Benjamin C. Cutting and Engraving Stone, Metal, Glass, Etc. Benjamin Chew Tilghman, assignee. Patent 108408. 18 Oct. 1870.