What can a nickel buy? In today’s world, not much, but in 1905, a nickel could purchase a one-pound loaf of bread, a ticket to ride on an urban trolley, a glass of draft beer… and a seat in a movie theater. Theaters in that time, however, were called something entirely different: a combination of the Greek odeon, meaning theater, and the five-cent price moving picture theaters charged for their shows – nickelodeon.

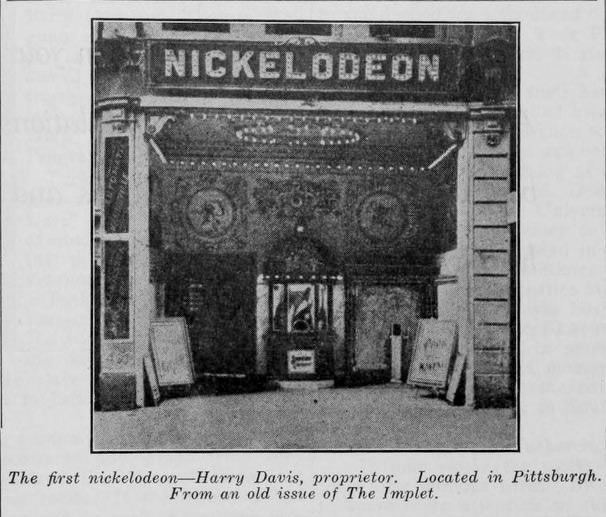

Nickelodeons began as a showman’s next step to making it rich in America. Harry Davis, born in England in 1870, immigrated to the United States at the age of nine and two years later entered the world of showmanship as a carnival hustler. He quickly learned effective business skills and how to appeal to crowds, discovering a passion for the field. By the time inventions such as Edison’s Kinetoscope, the French Cinematograph, and the American Vitascope entered the scene, Davis was a successful owner of several “dime museums,” penny arcades, and playhouses in a variety of locations. The entertainment value of moving pictures became apparent to Davis when he began showing them at these various locations as additional attractions. It seemed that everyone loved the movies, so enthralled by the lifelike images projected onscreen that one man reportedly drew his pistol and shot the image of a robber during one film. Davis soon realized that movies were the next “big thing” to hit the entertainment world and so decided to showcase them separately from his other enterprises. He teamed with Pittsburgh native John P. Harris, a respected employee and his brother-in-law, to open the Nickelodeon on Smithfield Street in Pittsburgh on June 19, 1905.

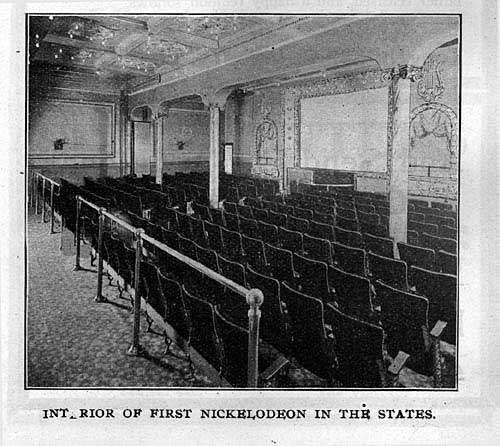

The Pittsburgh Nickelodeon seated 96 patrons in opera-house chairs, but at least one hundred more filled in standing room for every showing. These standing patrons crowded behind a bar on a raised platform in the back of the theater through all seasons, enduring any discomfort necessary to watch a fifteen-minute reel of film picturing, for example, a girl climbing a tree, someone eating an apple, or Edwin Porter’s infamous The Great Train Robbery. Many of these patrons were middle-class workers from the downtown Pittsburgh area whose jobs in the steel mills could not supply the two-dollar ticket prices of most opera and playhouses. Nickelodeons quickly became the workingman’s entertainment. The upper class could not resist, either – moving pictures were too much a spectacle to miss!

No business records from the time remain, but it is estimated that around 7,000 people patronized the theater each day between 8 A.M. and midnight. The first day the Nickelodeon opened, 450 people watched movies. By the second day, more than 1,500 people waited in lines. They were greeted with the best showmanship Davis could offer, for he was a believer in getting the most “bang for your buck,” a formula that nearly all nickelodeon owners followed. Phonographs or sideshow actors called out to attract crowds to their doors, while brightly lit signs towered as many as three stories above the storefront proclaiming the name of the theater and its current list of shows. Harris and Davis’s small storefront theater also boasted a variety of architectural flourishes such as crown moldings, embellished ceilings, and colorful paintings. Gilded statues and sconces greeted customers in the lobby, offering a rich “high class” atmosphere to the masses that could not normally afford it. What patrons didn’t know is that most of the decorations in Harris and Davis’s theater were extraordinarily cheap! Davis employed craftsmen who already worked in his regular theaters to embellish the Nickelodeon in the style of opera houses. If such opulence worked in those buildings, why not in a motion picture theater? And succeed it did. People flocked to the Nickelodeon to experience the classy ambience and view the latest film the way the upper class went to see the latest play or opera.

Historians estimate the building for the Nickelodeon on Smithfield Street cost Davis around $40,000 to purchase and decorate, but its worth to history is much more. This first theater was the impetus for nation-wide “nickel madness,” a sensation that spurred thousands of businessmen and showmen to open their own nickelodeons (with different names) in cities across the U.S. Within Pittsburgh alone, over one hundred nickelodeons opened in the years following Harris and Davis’ motion picture theater.

But while other cities were catching up, Pittsburgh was bounding forward in the motion picture business. Production companies and film exchanges burst onto the Pittsburgh scene shortly after the nickelodeon boom, providing theaters with fresh material so often that theaters could change programs multiple times a week. “Film Row” sprung up on Forbes Avenue between Ninth and Twelfth Streets, though most moved to Fourth Avenue by 1914 due to fire safety codes. The seven-story Seltzer Building, for example, housed a piano and organ company, a storage company, Selznick Productions, and three other film production companies all under one roof! Similar city blocks developed wherever nickelodeons spread, but Pittsburgh proudly housed the first and arguably the busiest. After all, before Hollywood existed, production companies first came to Pittsburgh for easy access to film exchanges, trade journals, and a wide variety of audiences.

The wide variety of audiences worried people about what would happen in the dark setting. Some people asked for movie review boards to judge the moral themes shown. The review boards inspired the ones still in place. Others wanted the movies to be shown with the lights on, “There were not many social spaces at that time that allowed sexes to intermingle in the dark for extended periods of time,” said Michael Aronson, an assistant professor of film and media studies at the University of Oregon, who is writing a history of the Pittsburgh nickelodeon boom. “The middle class already had a fear of immigrants and a fear of the dangerous other. Sex was bound into that.”

Pittsburgh’s key involvement in the history of the film industry is unknown to most, for over time the production companies relocated, the trade journals went out of print, streets were renamed and buildings were torn down. The only evidence of the Nickelodeon left is a bronze plaque hanging near 441 Smithfield Street, erected for the Nickelodeon’s 50th anniversary, and memorabilia held by John Harris’s descendants, the Hahn family. The building itself was torn down after only five years of operation to make way for larger occupancy (and more opulent) movie theaters more like the ones we know today. But the fact remains that the nickelodeon began as an idea unique to Pittsburgh, the first step to reaching today’s modern cinemas.

If only they still charged just a nickel!

Sources:

- Aronson, Michael G. “The Wrong Kind of Nickel Madness: Pricing Problems for Pittsburgh Nickelodeons.” Cinema Journal 42.1 (2002): 71-96.

- Aronson, Michael. Nickelodeon City: Pittsburgh at the Movies, 1905-1929. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 2008.

- Connelly, Eugene L. “The First Motion Picture Theater.” The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 23.1 (1939): 1-12.

- Jowett, Garth S. “The First Motion Picture Audiences.” Journal of Popular Film 3.1 (1974): 39-54.

- Keim, Norman O. Our Movie Houses: a History of Film & Cinematic Innovation in Central New York. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 2008.

- Lightner, E. W. “Pittsburg Gave Birth to the Movie Theater Idea.”The Dispatch [Pittsburgh] 16 Nov. 1919. The Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. 24 Mar. 2010 <http://www.clpgh.org/exhibit/neighborhoods/downtown/down_n71.html>.

- McNulty, Timothy. “You Saw It Here First: Pittsburgh’s Nickelodeon Introduced the Moving Picture Theater to the Masses in 1905.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 19 June 2005. 24 Mar. 2010 <http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/05170/522854-254.stm>.

- Mondello, Bob. “100th Anniversary of First-Ever U.S. Movie Theater.” Day to Day. National Public Radio. 17 June 2005. 24 Mar. 2010 <http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4707873>.

- Musser, Charles. Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company. Berkeley: University of California, 1991.

- Ramsaye, Terry. “The Rise and Place of the Motion Picture.”Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 254 (1947): 1-11.

- Stevenson, William H. “Address of William H. Stevenson at the Unveiling of Harris Memorial Tablet.” The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 12.4 (1929): 207-10.