"You ought to go to a boy's school sometimes. Try it sometime," I said. "It's full of phonies, and all you do is study so that you can learn enough to be smart enough to be able to buy a goddam Cadillac some day, and you have to keep making believe you give a damn if the football team loses, and all you do is talk about girls and liquor and sex all day, and everybody sticks together in these dirty little goddam cliques. The guys that are on the basketball team stick together, the goddam intellectuals stick together, the guys that play bridge stick together. Even the guys that belong to the goddam Book-of-the-Month Club stick together.”

Countless students, parents, and American readers have read this passage over the last half-century. The irritable tone, discussion of ‘phonies,’ and vulgar language makes it easily recognizable as the voice of J.D. Salinger’s character Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye. Salinger’s novel has become a staple in American literature, one of the most popular and talked about books in the twentieth century, and has sold over sixty-five million copies. But, perhaps what Salinger didn’t realize when he wrote this passage is that the ‘goddam Book-of-the-Month Club’ would be the catalyst to bring his work to the status it claims today.

Today, we live in a world where literature, media, and information are accessible at our fingertips. With the click of a mouse we can access books in an instant, and novels can become bestsellers overnight. Online book orders, internet booklists, and the e-book craze have allowed literature to remain a stable form of popular culture. Rewind to 80 years past, and books had a somewhat different role in our society. Literature, like many forms of art, was considered a privilege of the elite, intellectuals, and the upper class. For most Americans, acquiring new and quality texts wasn’t nearly so simple as it is today. And it was even more difficult for authors to market their releases and actually turn a profit. But, the atmosphere of reading in America and the publishing industry changed forever in 1926. The small town of Camp Hill, Cumberland County produced a big idea that would have lasting affects on not only literature, but also marketing and big business into the twenty-first century. This idea, which would allow authors like Salinger to distribute their books to the widest readership in the United States, was the Book-of-the-Month Club.

In 1913, while Henry Ford was creating the first assembly line, an aspiring playwright named Harry Scherman joined a group of intellectuals in Greenwich Village in Manhattan to discuss the works of Picasso, Matisse, and Duchamp and share their artistic efforts to make sense of modernity. Ford’s idea of mass production in the automobile industry led to mass consumption of vehicles. In the same year, the astonishing Armory Show exhibit in New York City introduced Americans to their first experience with modern art. The group of young bohemians in Greenwich had no idea that the young Harry Scherman’s contribution to defining modernism—the Book-of-the-Month Club—would be more closely related to the assembly line than that of the Armory Show.

As Harry Scherman met with his scholarly and artistic companions in 1913, he struggled to find a meaningful career. Scherman, though fascinated with literature and Shakespeare, spent time studying economics and finance at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and later studying law, though he never finished either degree. He began working as a copywriter for Ruthrauff & Ryan, a Manhattan advertising firm, to support his creative writing. Upon coming to New York, publishers quickly rejected his plays and stories. However, he found success a few years later as a mail-order copywriter at the prominent business firm, J. Walter Thompson.

Scherman’s increasing talent in copywriting and previous attraction to literature directed him toward an interest in book marketing. He remarked later that he “noticed particularly how people could be influenced to read books by what was said about them.” At the same time, Publishers Weekly announced that “the world is still looking for a publisher who will ‘discover and invent’ a new method which shall be practical and effective for the distribution of books of general literature.” As if answering the magazine’s proclamation, Harry Scherman joined up with Charles and Albert Boni, members of Scherman’s Greenwich Village group, to create a new idea in book sales in 1916.

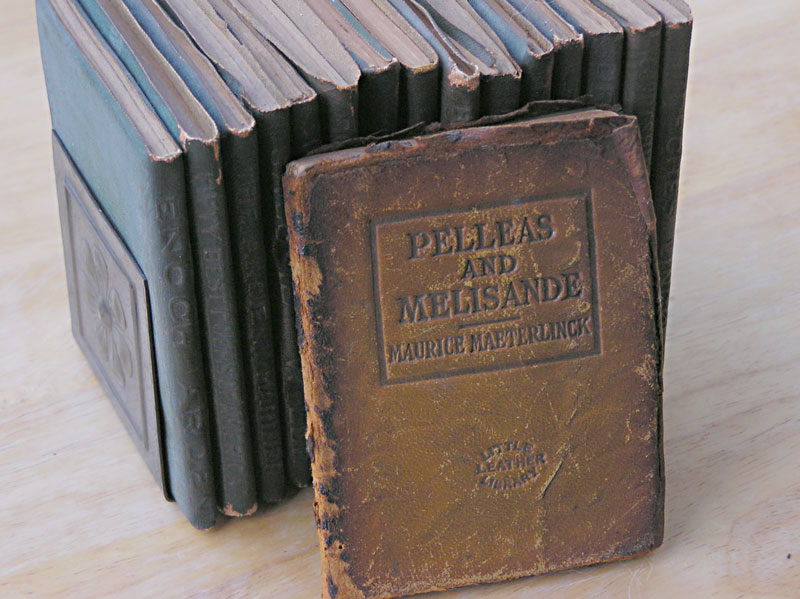

The three friends—along with Max Sackheim, an associate of Scherman’s from Ruthrauff & Ryan—created a unique business model, which they named the Little Leather Library (LLL). The small company advertised to select and mail out “30 Great Books for $2.98” nestled inside a box of chocolate treats. The team’s book marketing scheme aimed to target the sale of thirty classics to the ‘general reader.’ The project involved a partnership with Whitman Candy, so that a box of candy and leather bound book could be joined in a package. Sherman quit his position at the Thompson agency to become president of the LLL and oversee production. Their collection grew to sixty titles, all which were in the public domain because, as Sherman explained, “we couldn’t pay any royalties.” Rather than use outside marketing, Sackheim suggested to market their books directly through the mail. Scherman’s ‘Library’ was extremely well received by the public, and in just five years they sold an unprecedented thirty million copies.

Growing from the Little Leather Library and the idea of marketing to the average American reader, Scherman, Sackheim, and a new business partner Robert Haas, sought to establish a large-scale book distribution through mail order. This time they would market newly published books, rather than sets of the classics. The concept was a merchandising scheme with an efficient and accelerated production system. Scherman recognized a problem in publishing: publishers were required to go through traditional bookstores to reach consumers. These bookstores were primarily concentrated in urban areas and the East Coast in the 1920s. The three partners decided to open a distribution center in the small borough in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, where they could bypass book retailers and ship their products directly to customers.

Sackheim, reflecting on their process of inventing a new brand, described: “There we were with several elements, each of which had some merit. We knew the ‘pull’ of popular selection. We knew the importance of repeat sales. We had already experienced the ‘feel’ of the book club potential. It was only a step to the use of popular books and the Book-of-the-Month Club idea.”

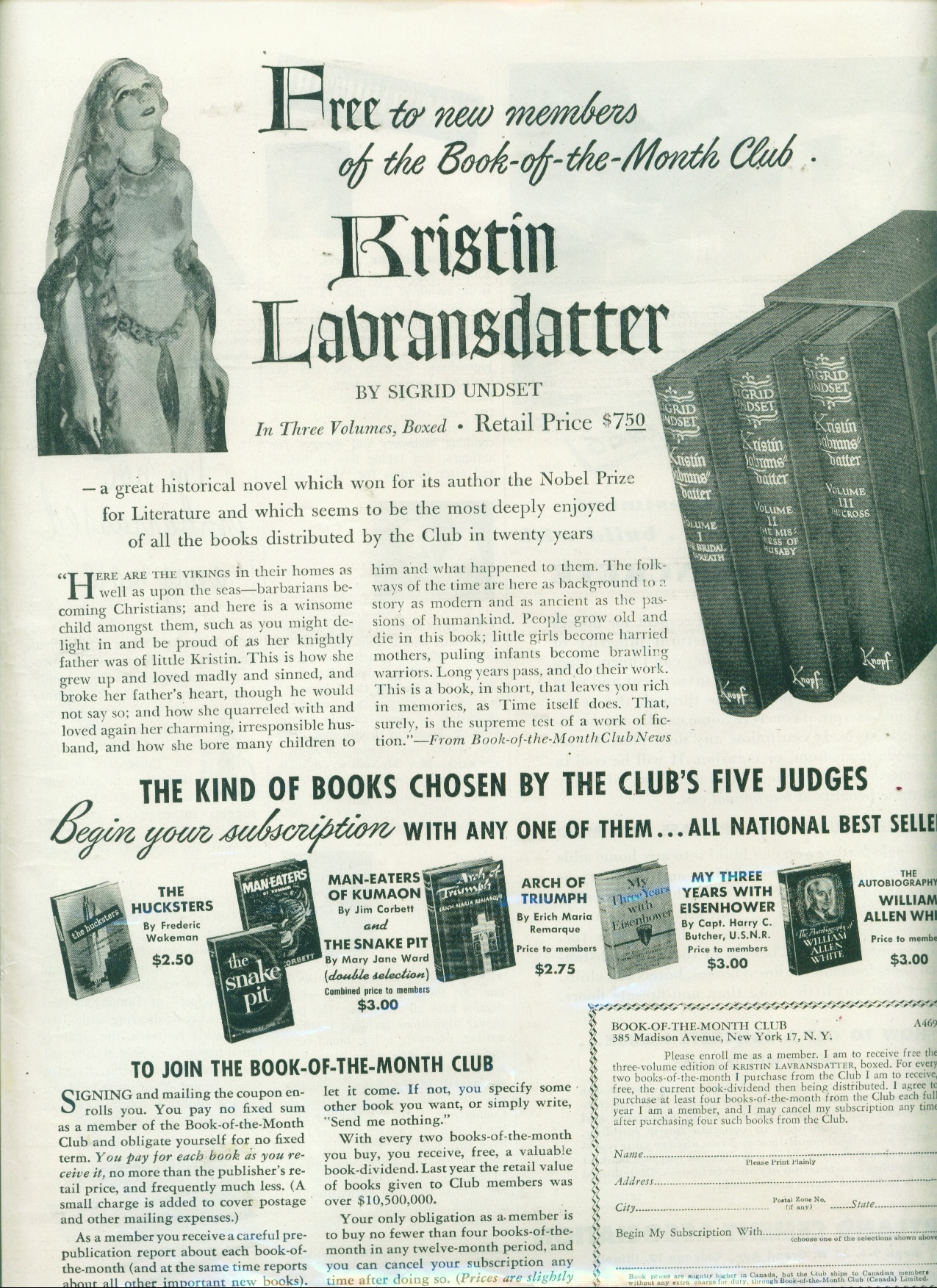

Their brand, the Book-of-the-Month Club, was based on two pivotal elements that would increase accessibility and opportunity for book sales. First, a panel of editorial experts would discuss and select a new book each month to present to its readers. Scherman chose five literary authorities—Dorothy Canfield, Harry Canby, William Allen White, Heywood Broun, and Christopher Morley—to make up the first editorial panel. Each was an established and respected writer, journalist, or editor. Readers were assured that they were receiving “the best new books published each month,” and thus, would save time and have the recommendations of knowledgeable literary critics. This also eliminated the limitations of the Little Leather Library, which had a finite set of established classics to market. As Radway writes in her analysis of the company, “Theoretically the Book-of-the-Month Club would never run out of books to sell or exhaust the desires and needs of potential customers.”

The second key component of the Book of the Month Club was the subscription model. The model, unlike traditional bookstores, would persuade potential readers to buy more than just a few individual titles—it would reach a new audience. Readers in 1926 had made it a habit of visiting a bookstore, usually with a particular author in mind. By subscribing to the Book of the Month Club, readers would receive a new book every month and thus agree to purchase a group of books over a period of time without traveling to a bookstore. The automatic approach would allow BOMC to rely on future books sales before the titles themselves were released.

But again, this would only be successful because of the first element, the editorial panel. Scherman’s task was to authorize the selections and create a reputable brand through which consumers would be willing to buy titles and authors unknown to them. He explained later to the Columbia Oral History Interviews: “You had to set up some kind of authority so that the subscriber would feel there was some reason for buying a group of books, so that he’d know he wasn’t buying a pig in a poke, and also that he wasn’t buying books which were suspect.”

Scherman’s success with the model was aided by developing the abstract idea of “new books” to customers. Through heavily marketed advertisements, the Book of the Month Club constructed the rationale that readers would benefit from receiving a variety of expert-endorsed books regularly rather than rely on their own resources. According to Caitlin Gannon, a writer on popular culture, “Sherman targeted the desire of the club’s middle-class subscribers to stay current and was able to successfully convince the public that owning the newest and best objects of cultural production was the most expedient way to accomplish this goal.” Americans embraced the concept. In the first year there were just 4,000 subscribers, but by 1927 there were 60,058 members.

Though a new class of readers was formed through subscriptions, particularly within the middle-class, not all readers were comfortable with this innovation in literature. The Book of the Month Club felt heavy criticism from skeptics concerned that the Club would treat books as commodities, purchased purely for their novelty, rather than true culture objects. The mail-order marketing scheme threatened the idea that literature should be published because of its high quality, not because it appealed to the taste of the general public. Society’s elite and intellectuals felt the taste of mainstream readership for the BOMC did not include anything “avante-garde or experimental” and that this economic group would have the most influence when marketing texts.

Despite criticism, Harry Scherman’s idea continued to increase in popularity. In just twenty years, the number of subscribers grew to 550,000, making the Book of the Month Club a household name. In a 1955 article in Barron’s National Business and Financial Weekly, the magazine announced that ‘culture [was] paying off for this unique venture.’ While other companies were struggling with post-war setbacks, the Book of the Month Club had earned $16.6 million in sales the previous year, the article attributing stability to people’s continuous desire from cultural products.

Scherman’s editorial board also silenced critics with their remarkable and winning selections. William Zinsser, an executive editor for the BOMC in the 1970s and 80s, described that though the editorial board must answer questions like “Have we recently offered a book on the same subject?” and “How have the author’s previous books been received?” to accommodate the needs of the members, they feel one even greater responsibility: “to the book.” By the Club’s sixtieth anniversary in 1986, the company boasted 25 of its authors having won the Nobel Prize and 79 winning the Pulitzer Prize. Over the decades, the board chose some of the most enduring novels of the century for their monthly reads, including Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, and Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird. Though these novels are considered classics today, much of their circulation can be attributed to their spot on the BOMC selection list. Authors would give publishing rights to BOMC, and through distribution to club members book sales would be instant and astronomical in comparison to other publishing houses. The Club’s influence on a book’s success in the market is parallel to the naming of a text to Oprah’s book club today.

The literary authority of the editorial panel had been clearly established by the latter quarter of the twentieth century. But, as the publishing industry grew increasingly more efficient and competitive, three of the five judges were dismissed in 1988. James Kaplan expressed in his New York Times article the next year the change readers felt in the Club’s focus:

The news sent out a shock wave into the world of American culture,” he said, “Weren’t those judges appointed for life? One imagined them sitting around a big oak table, gently slipping into wordy dotage, all pipes and suede elbow patches and cocktails and (of course) piles and piles of books. Fired? The word had a most un-booklike ring.

And in fact, there was an imminent shift in values for the Club by the 1990s. Now under the ownership of media conglomerate Time-Warner, the BOMC felt pressure to increase profits and compete with discount retail book chains. By 1994, the editorial board was dissolved altogether. Sarah Lyall wrote for the New York Times that the editors would no longer “enjoy the unusual luxury of meeting once a month to discuss and argue about books,” but rather as a ‘sign of the times’ the company would rely on freelance readers and staff editors. Two years later in the Times, Doreen Carvajal criticized the Book of the Month Club for “push[ing] bestsellers instead of best writing.”

The 1990s marked a critical period of the company conforming to market pressure and competition—even expanding the Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania distribution center by 200,000 square feet—but the ideals of Harry Scherman’s original business model were not lost. Though the authority of the BOMC to select quality texts had slipped away with the editorial board in 1994, a panel of four new judges was reestablished in 2001 in order to restore the Club’s influence in literature. Larry Shapiro, Book-of-the-Month Club’s editor, announced the reconfigured judge’s panel would promote less-well-known books. ‘‘There has been a shift back toward an interest in going beyond the obvious among our membership -- much more than there was five years ago,’’ he said. ‘‘People are interested in buying books that go beyond what they could buy anywhere, provided we present it with the right authority and the right encouragement.” The return of the judges’ panel helped the Club persist; at the beginning of the twenty-first century there were more than one million subscribers.

The Club continues to stand the test of time as it now crosses multiple generations of readers. ‘‘My mother belonged to the Book-of-the-Month Club,” said Anna Quindlen, a current editorial judge, “she took it very seriously. It was one of the main sources of books in our life.” To keep up with online booksellers and franchise bookstore chains, BOMC has now introduced BookSearch Plus, allowing members to shop for particular books outside monthly selections (much like Amazon.com). They’ve also implemented Smart Readers Rewards, a program that enables members to choose special interest categories for which they’d like to receive titles. The Book of the Month Club is now owned by Direct Brands.

The Book of the Month Club grew from three colleagues discussing literature to the most influential marketing scheme in the publishing industry. Harry Scherman, hailed “the father of the mail-order business,” not only shaped marketing in the twentieth century, but also brought literature to an entirely new audience of middle-class readers. Controversial or risky novels like J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher and the Rye gained popularity and circulation through the Club’s recommendation and reputation. The central element of the Book of the Month Club, which has allowed the company to thrive year after year, is Harry Scherman’s central philosophy: “If you are to deal with or think about the American people en masse, you must regard them as little different from yourself,” an ideal readers continue to appreciate and enjoy.

The Center would like to thank Eric of Miss Pack Ratz Advertising Collectibles, Scott Hanley at Angular Uncomformities and Karen Hartmann at Direct Brands for their assistance illustrating this article.

Sources:

- Arnold, Martin “MAKING BOOKS; For Book Club, It’s Back to Things Past” New York Times 25 Jan. 2001: 3.

- Barclay, Dolores A. Associated Press. “BOOK-OF-THE-MONTH CLUB GETS READY TO CELEBRATE 60 YEARS OF GOOD READING” Chicago Tribune (pre-1997 Fulltext) 20 Mar. 1986: D2.

- Book of the Month Club. 2011. <http://www.bomcclub.com/>.

- “Book-of-the-Month Club to expand in Mechanicsburg, Pa.” Business Wire 30 Jan. 1997.

- “Books: Easy Economics.” TIME Magazine 28 Mar. 1938.

- Carvajal, Doreen “Triumph of the Bottom Line; Numbers vs. Words at the Book-of-the-Month Club” New York Times 1 Apr. 1996: E1.

- Gannon, Caitlin L. “Book-of-the-Month-Club.” St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Ed. Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast. Vol. 1. Detroit: St. James Press, 2000. 318-319.

- Kaplan, James “Inside the Club” New York Times 11 June 1989: 62.

- Kirkpatrick, David D. “The Book-of-the-Month Club Tries to Be More Of-the-Moment; New Judges and Niche Marketing Are Part of a Comeback Plan” New York Times 28 June 200: E1.

- Lee, Charles. The Hidden Public: The Story of the Book-of-the-Month Club. New York: Doubleday & Co, 1958.

- Lyall, Sarah “Book-of-the-Month Club to Dissolve Advisory Panel.” New York Times 15 Sept. 1994: C15.

- Radway, Janice A. A Feeling for Books: the Book-of-the-Month Club, Literary Taste, and Middle-class Desire. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Radway, Janice A. “The Book-of-the-Month Club and the General Reader: On the Uses of “Serious” Fiction” Critical Inquiry 14. 3 (1988): 516-538.

- Rubin, Joan Shelley. “Self, Culture, and Self-Culture in Modern America: The Early History of the Book-of-the-Month Club.” The Journal of American History. 71. 4 (March 1985): 782-806.

- Sapinsley, B. C. “Book-of-the-Month Club: Culture Is Paying Off for This Unique Venture.” Barron’s National Business and Financial Weekly 14 Nov. 1955.

- Scherman, Harry. The Promises Men Live By: A New Approach to Economics. New York: Random House, 1938.

- The Well-stocked Bookcase: Sixty Enduring Novels by Americans Published Between 1926-1986. Camp Hill, PA: Book of the Month Club, Editorial Board, 1987.

- Wyatt, Edward “Book-of-the-Month Club Takes Steps to Get Out of Trouble.” New York Times 12 Jan. 2005: E1.

- Zinsser, William K. A Family of Readers: An Informal Portrait of the Book-of-the-Month Club and Its Members on the Occasion of Its 60th Anniversary. New York: Book-of-the-Month Club, 1986.