During the French Revolution, French aristocrats fled the extraordinary and prolonged violence in their country and came to the wilderness of present day Bradford County, Pennsylvania. These political refugees began settling into the “Azilum” in 1793. During the colony’s 10-year existence, the settlement was a bustling gritty “frontier” settlement inhabited by nobles unaccustomed to the rigors of “common” life. Both American frontiersmen from the area and French aristocrats had contact with a social class they would have never met otherwise. The settlement slowly grew until it was abandoned in 1803. Azilum would remain lost in history until its revitalization that began in 1953. Azilum today is a historical and archaeological site where anthropologists and sightseers go to witness history first-hand.

French Azilum began as an escape effort followed shortly by a business venture. When Comte Louis de Noailles, a French Naval officer, and Omer de Talon, a French nobleman, fled France for fear of execution, they came up with the idea for a settlement by and for refugees. They enlisted a group of influential Philadelphians, including Robert Morris, and John Nicholson, who also thought that it would be profitable to buy land in Northern Pennsylvania and start a colony for fleeing French nobles. They named their newfound venture the Asylum Corporation, since the French settlers were seeking asylum in the United States. However, once settlers got to the site they decided to change the official name of the settlement to “Azilum,” since it had fewer connotations with the mentally insane than “Asylum.” After the idea was proposed and money obtained, the building in present-day Bradford County began quickly.

In the summer of 1793, trees were cleared on 300 of the 200,000 acres that the new Asylum Corp. had purchased. Within three months, more than 50 log cabins had been built, a town center was established, and settlers had begun to arrive from Europe. Once occupancy increased, construction began on “Le Grande Maison,” a massive 3,600 square foot mansion fit for royalty. According to Louise Welles Murray, this mansion was supposed to be the home of the Queen Marie Antoinette and her children. However, she was executed before she and her children could escape France.

During their time there, more than 100 noble settlers set up businesses and produced such goods such as pots, furs, and baskets. They also set up trading posts, schools, and churches, including the first Catholic Church in the present day Diocese of Scranton. While these nobles lived in the wilderness, basic and independent, some of the luxury goods that they were accustomed to as nobility were brought to Azilum on barges up the Susquehanna River.

All was going well in Azilum, despite social tension between the aristocratic French and Anglo-American working families, when word came that the king had been executed. This news only added to the restlessness, but they were too afraid to return to their home country due to violence. Finally, when Napoleon Bonaparte gained control of the country, he sent out notifications of amnesty to all the émigré nobles. Missing all the perks of being noble, many of the occupants of Azilum left in 1803 to return to comfort in France. With a large share of its inhabitants gone, the local economy of Azilum collapsed, causing all the families that stayed behind to disperse. The remaining families either struck it up and moved south, or settled in emerging towns across Northeastern Pennsylvania. By 1804, Azilum was deserted. As time passed the site, and its history, passed into obscurity.

It is not known whether Marie Antoinette ever knew about Azilum as a potential refuge. Though it is believed she was offered several plans of assistance to help her escape prison, none was ever attempted. As she was executed in the same year and month that the colony was established, it is doubtful that the Grande Maison was built exclusively with her in mind. Nonetheless, the site was still host to significant historical figures. Most notably was Louis Philippe, the last king of France. While only a footnote on Louis Philippe’s tour of America, his stay at Azilum brings extra attention, importance, and fame to this French settlement. In a letter to his advisor, Francois Guizot, Louis-Philippe, known as the “Citizen King” during his reign from 1830 to 1848, stated that his years in America, including his visiting of Azilum in Bradford County, influenced his political beliefs as king.

Influence was not a one-way street however, for in the 1790s Americans had their own opinions changed by these French aristocrats. While the majority of the public still had respect for royalty, it gave Americans reaffirmed pride that they were free from the tyranny that monarchy represented. The settlement is also of local importance for Bradford and the surrounding counties. Many of the families that did not return to France settled in existing towns in Northeastern Pennsylvania or founded new ones. The Homets, LaPortes and Lefevres were three of the largest families who did not return to France. Two of them, the Homets and LaPortes, have towns in Northeastern Pennsylvania named after them: Homet’s Ferry and Laporte, respectively.

No other American settlement had a society like the Azilum. Mainly upper-class, these Frenchmen were transplanted to the backwoods of Pennsylvania, causing these aristocrats to have a new respect for the castes below them. The majority of the occupants were French nobility, not used to the rigors of everyday life. They eventually adapted, doing work and living in conditions they never believed possible back in France. Still, the French settlers clung onto parts of their nobility, and its tradition, like fancy dresses, elaborate dinners, and whatever luxurious goods they could get their hands on.

Azilum was largely abandoned until the 1830s when Rep. John LaPorte, a son of one of the original LaPorte Azilum settlers, returned to the region and built a home and farm there. None of the buildings on the site, including his home, are from the original settlement. When the refugee colony disbanded, neighboring residents dismantled the wood houses, their frugality not letting cut and measured logs go to waste. French Azilum Inc., operates the site in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Museum exhibits are in the LaPorte House and throughout the grounds. The current site has twenty-two acres of the original Azilum settlement all open for exploration.

The uniqueness of French Azilum has long made it an attractive subject for historical fiction. In 1948, I Thee Wed by Gilbert Gabriel and Asylum for the Queen by Mildred Jordan both used historical details of the Azilum as a backdrop for their thrilling adventure/romance tales. In I Thee Wed, a dashing young Scots-American pioneer falls in love with the mysterious singer, Mademoiselle Marin, who was featured in two real Azilum diaries. Due to her resemblance to Marie Antoinette, the fictional Marin is to act as the Queen’s double if she manages to escape France, until Marin is captured by Judge Antoine Omer Talon, a historical person that Gabriel casts as the villain.

The hero of Jordan’s Asylum for the Queen is Pierre de Michelait, a romantic young man and former page to the Queen who becomes involved in attempts to rescue the royal family. Like Gabriel, Jordan also casts Mademoiselle Marin, this time as secret agent for the French Convention who is tracking the Dauphin’s (unhistorical) escape to America. Both authors utilize the colonial Pennsylvania landscape from the icy mountain peaks to the virgin woodlands that have since been lost.

Azilum found itself in popular fiction again in 1989 with Jeanne Mackin’s The Frenchwoman, in which Julienne, a former gutter rat who rose to seamstress of Marie Antoinette, is lead to the settlement. The town also inspired Mark Seinfelt’s Henry Boulanger of Mushannon Town, a semifinalist in Amazon.com’s 2008 Breakthrough Novel contest. Seinfelt’s narrator, Henry, is a French-born Revolutionary War solider who, after the war, is asked to help build Mushannon, a town for French refugees and a fictional version of Azilum. The story focuses on his transcontinental journey from the corrupt 18th Century Europe to the unspoiled American frontier.

In 2009, new archeological excavations caused renewed interest in Azilum. Maureen and Daniel Costura, Cornell doctoral students directed the dig. Using thermal imagery and records of Azilum, they first located the foundations of some of the original buildings. Following the standard procedure for architectural digs, the Costuras created excavation units at the most promising sites. A unit is a 36 square-foot hole in which archaeologists excavate layers of dirt, looking for household artifacts left behind by Azilum’s settlers, and the foundations of buildings. A major objective for the archaeological team was to locate and excavate Azilum’s main kitchen.

“Archeology isn’t rocket science, it’s digging, so we give them [the volunteers] a quick tutorial on how to actually excavate,” Maureen Costura said in a WNEP 16 interview with Renie Workman. The volunteers used trowels, pans and buckets to scoop up the dirt and check for any little artifacts. The artifacts were usually pieces of ceramic, glass, old nails, or the odd tooth, most likely from a pig. At the end of the day the two Cornell students bagged all the items and label them according to their importance, classification, and the unit that found it. By the end of summer 2009, over five units had been unearthed containing numerous artifacts. With a clear idea of where the buildings were and how they looked, historians and visitors will have a better view of what life in Azilum was like.

Just as excavations are more than just digging, Azilum did a lot more than just house a bunch of French aristocrats. When the American government, businesses, and citizens accepted these French refugees, it created a precedent of accepting refugees from political, economic, and social strife. This was the first time in the United States brief history that it got entangled into the domestic dispute of another nation, and we welcomed in the refugees with open arms. While Azilum was a business venture, it also paid a cultural debt to both the French monarchy and to the citizens of France. While we owed the French Monarchy for its help as our sole ally during our Revolutionary War, we also felt compelled by the French plea for democracy, since it so closely mirrored ours. By offering the French aristocrats asylum in the United States, we settled out debt to the monarchy and to the people of France. By having the aristocratic leaders of the nation safely hidden away in America, the French people had an obstacle out of their way to freedom.

The Statue of Liberty was a grand gift from the French Government in 1886 to commemorate the friendship forged between the two nations during America’s Revolutionary War. Inscribed on the base of the statue is “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me. I lift my lamp beside the golden door.” Written by Emma Lazarus, this quotation is a perfect representation of America’s acceptance of French refugees. America took in France’s tired and homeless and put them in French Azilum of present-day Bradford County, where they lived in the wilderness until it was safe to return to their nobility in France. Hundreds of years later Azilum is again receiving visitors, this time to uncover the history that this site holds.

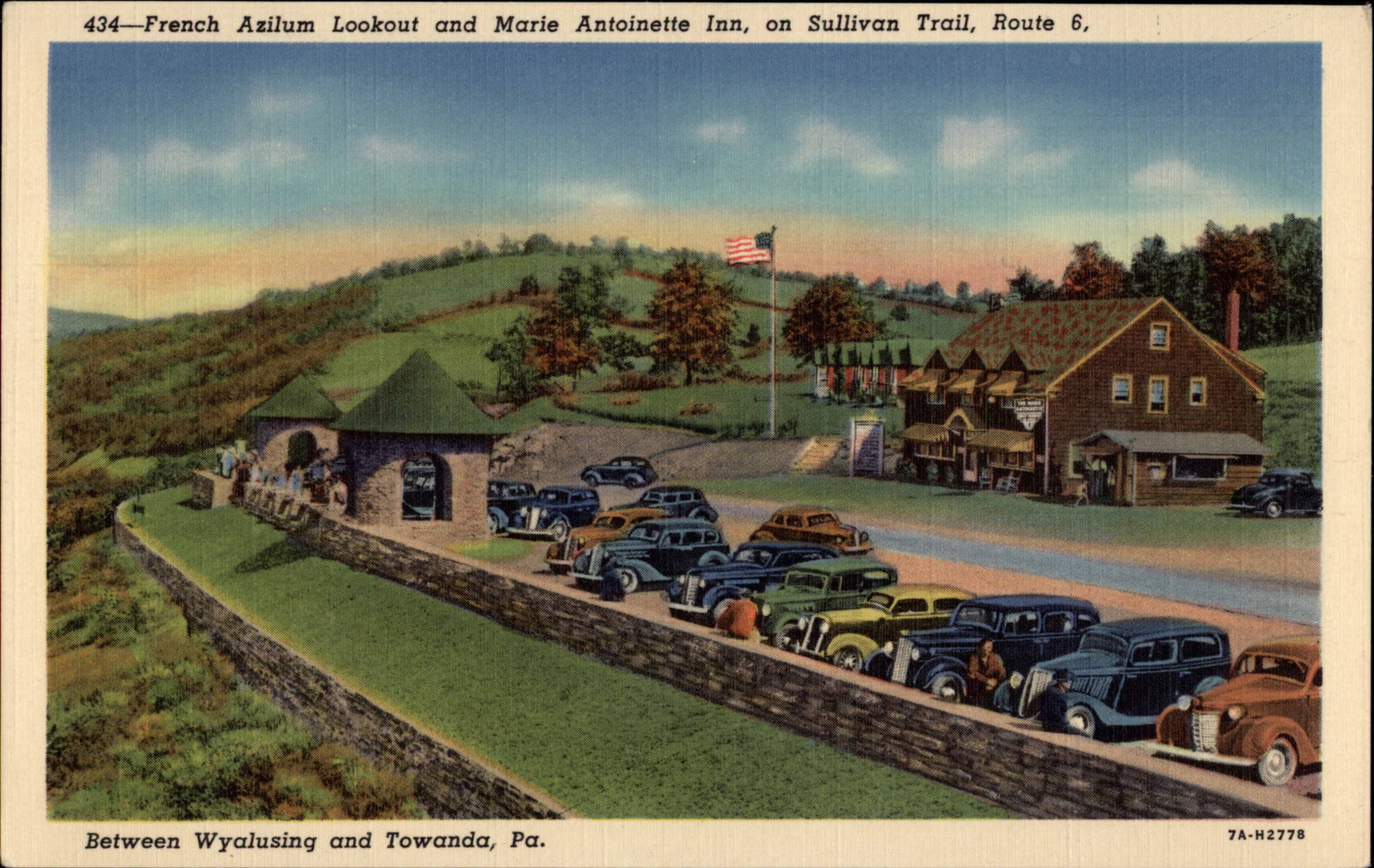

The Center wishes to thank the French Azilum Historic Site and Cardcow.com, as well as individuals Stefan Poost and David M. Hilsdorf for their assistance in illustrating this story.

Sources:

- Biles, John A. Historical Sketches Pertaining or Linked with Asylum. Geneva, New York: The W.F. Humphrey Press, 1931. N. pag. PDF file.

- Blanc, Louis. The History of Ten Years, 1830-1840: or, France Under Louis Philippe. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard, 1848. Google Book Search. Web. 10 Nov. 2009.

- “Books.” Mark Seinfelt. Web. 22 Sept. 2010. <http://www.markseinfelt.com/books.php>.

- “Bradford County Pennsylvania.” Bradford County Pennsylvania. Bradford County, Nov. 2009. Web. 7 Nov. 2009. <http://bradford-pa.com/>.

- Carlyle, Thomas. The French Revolution: A History Volume I. N. pag. Google Books, n.d. Web. 7 Nov. 2009.

- Digging for History at French Azilum. WNEP 16, July 15, 2009. WNEP 16. Web. 10 Nov. 2009.

- French Azilum: Historic Site. French Azilum Inc., Oct. 2009. Web. 25 Oct. 2009. <http://www.frenchazilum.com/index.html>.

- Gibson, Alexander D. “The Story of Azilum.” The French Review 17.2 (1943): 92-98.

- Kashuba, Cheryl A. The Times- Tribune. The Scranton Times-Tribune, 19 July 2009. 10 Nov. 2009.

- Mackin, Jeanne. “My Works - Jeanne Mackin.” Jeanne Mackin. 22 Sept. 2010. <http://www.jeannemackin.com/works.htm>.

- Mann, Robb, and Diana DiPaolo Loren. “Keeping Up Appearances: Dress, Architecture, Furniture, and Status at French Azilum.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 5.4 (2001): n. pag. PDF file.

- Mattise, Alexa. E-Mail interview. 28 Oct. 2009.

- Murray, Elise. “French Refugees of 1793 in Pennsylvania.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 87 (1944): n. pag. Web. 8 Nov. 2009.

- Murray, Elsie. “French Experiments in Pioneering in Northern Pennsylvania.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 68.2 (1944): 175-188. JSTOR. Web. 9 Nov. 2009.

- Murray, Elsie. The William and Mary Quarterly 3rd ser. 5.4 (1948): 616-18.

- Murray, Louise Welles. The Story of Some French Refugees and Their Azilum 1793- 1800. Athens, PA: Tioga Historical Society, 1903. N. pag. PDF file.

- Picou, Margo Fox. Personal communication with Alan Jalowitz. 17 Oct. 2010.

- Sosnowski, Thomas C. “A ‘Noble’ Attraction: French Revolutionary Exiles in the Trans-Appalachian West.” OAH Newsletter (Fall 2004): 31-40. PDF file.

- Spaeth, Catherine T.C. “America in the French Imagination: The French Settlers of Asylum, Pennsylvania, and Their Perceptions of 1790s America.” Canadian Review of American Studies 38 (Nov. 2008): 246-270.

- Tassin, Susan. Pennsylvania Ghost Towns: Uncovering the Hidden Past. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2007.

- Worman, Edward A. “The 1790’s French Azilum in Pennsylvania.” Pennsylvania Magazine Apr. 1989: 25-30.

Novels about this subject

- Gabriel, Gilbert W. I Thee Wed. New York: Macmillan, 1948.

- Jordan, Mildred. Asylum for the Queen. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1948.

- Mackin, Jeanne. The Frenchwoman. New York: St. Martin’s, 1989.

- Seinfelt, Mark. Henry Boulanger of Mushannon Town: A Novel of the American Revolution. [BookSurge], 2008.