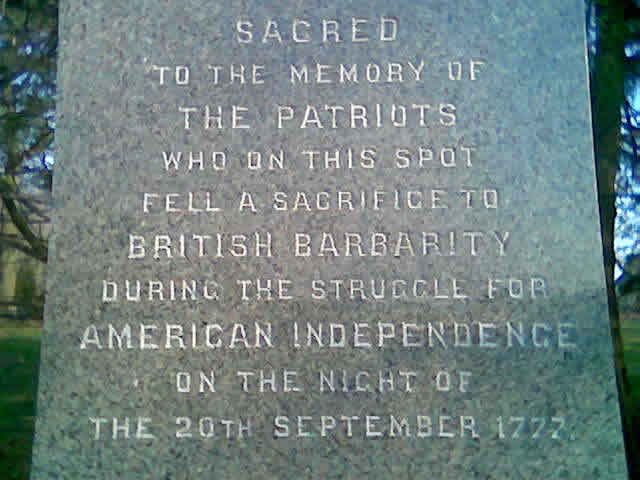

At first glance, the Borough of Malvern, Chester County appears to be a typical Philadelphia suburb. There are a few basketball courts, a local Italian restaurant, antique shops galore, and a bustling saloon to name but a few popular spots. However, there is a bit more to this small town than meets the eye. Deep in the borough, through the back roads, over a few speed bumps, and past the tee ball fields lies the site of one of the bloodiest, most horrific atrocities of the Revolutionary War. When comparing this battle to others in the Revolutionary War, a minimal number of American soldiers perished. However, the manner in which the attack was executed is what gives it the title of the Paoli Massacre.

To gain a better understanding of this battle in particular, it is important to be familiar with the events leading up to it. According to The Encyclopedia of American Studies, in the summer of 1775 Major General George Washington took command of the American militia shortly after a decisive battle at Bunker Hill. Throughout the rest of 1776, the British landed several decisive blows against Washington and his troops. The Redcoats defeated Washington in the Battle of Long Island, took control of New York City, won another battle at White Plains, and forced the Americans to abandon their garrisons at Forts Washington and Lee. By the turn of the year, however, Washington had defeated the Hessians (German soldiers hired by the British) at the Battle of Trenton, and was also victorious at Princeton. Then came the Philadelphia Campaign. After being out-maneuvered by the British at the Battle of Brandywine, and a demoralizing rainout at the Battle of the Clouds, the American troops were in need of a victory. Instead, they were massacred by the British.

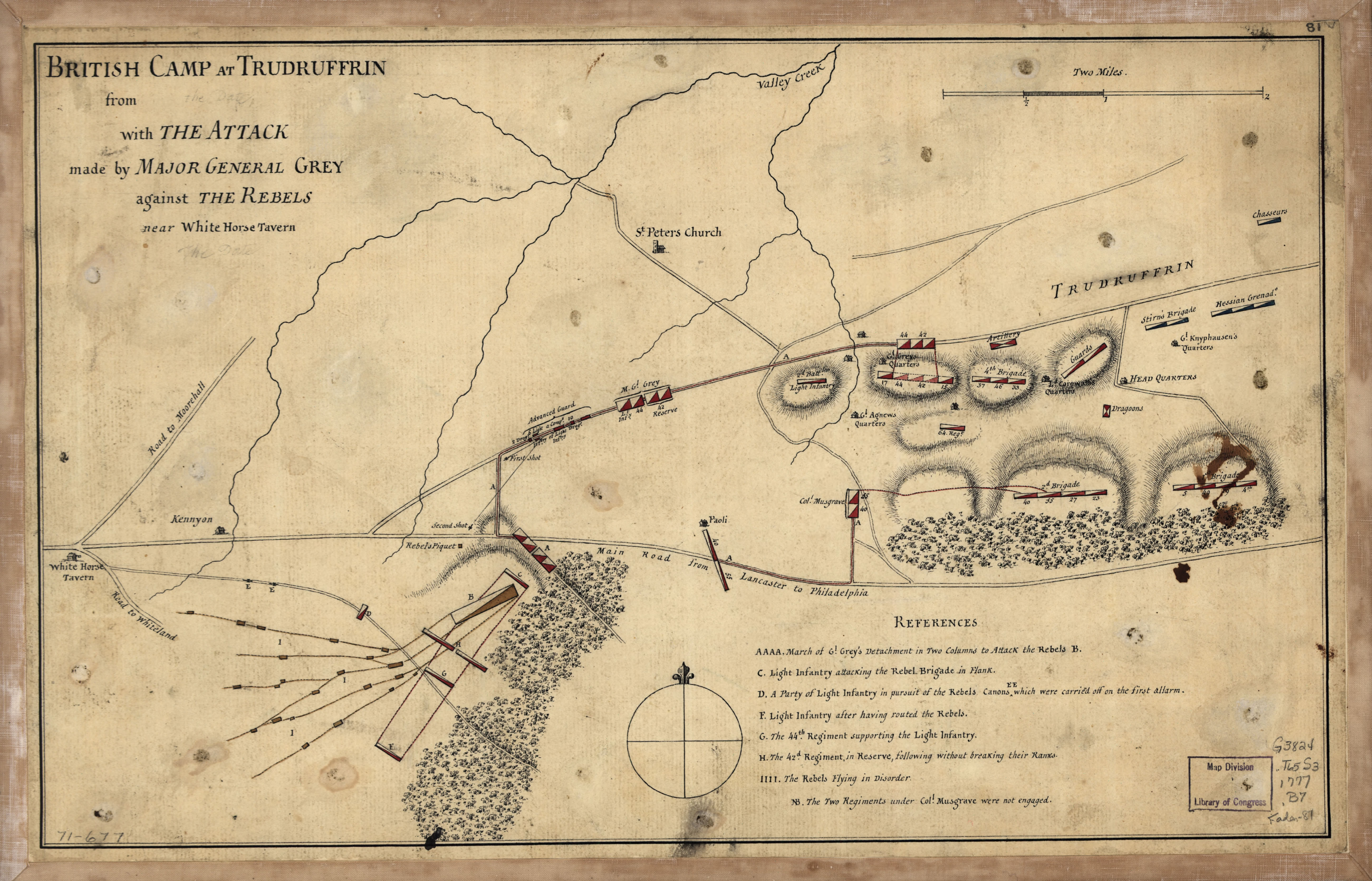

By the morning of September 20, 1777, one would have thought that General Washington’s army was in a great strategic position. His troops were camped across the Schuylkill River, preventing the British from taking the capital of Philadelphia, and his other generals were beginning to surround the enemy. As stated by Captain von Munchhausen in Thomas J. McGuire’s book, The Battle of Paoli, “(Washington) has detached 4,000 men to this side of the Schuylkill, 2,000 of whom are on our left flank and 2,000 are close behind us, under the command of General (Anthony) Wayne.” Assuming that the British were unaware of his troops’ positions, Washington was hoping to have General Anthony Wayne attack them from behind. Clearly, based on Captain von Munchhausen’s statement, the British knew exactly what the Americans were up to. This would prove to be the downfall of General Wayne’s troops at Paoli.

Following the instructions of General Washington, General Wayne and his troops were in hot pursuit of the enemy, and were planning to attack the British from the rear. They decided to make camp by the Paoli Tavern in Pennsylvania (approximately 25 miles from Philadelphia) and devise their plan. However, unbeknownst to Wayne, the British had their own set of plans. According to the Independence Hall Association’s account of the massacre, at approximately 1:00 a.m. on September 21, the British came howling through the woods right into the slumbering American troops. It wasn’t necessarily the act of the surprise that differentiated this battle from others; it was simply one key order that British General Charles Grey made to his troops. As stated on the Independence Hall Association’s site, British Major John Andre describes General Charles Grey’s orders:

It was represented to the men that firing discovered us to the Enemy, hid them from us, killed our friends and produced a confusion favorable to the escape of the Rebels and perhaps productive of disgrace to ourselves. On the other hand, by not firing we knew the foe to be wherever fire appeared and a charge (of bayonets) ensured his destruction; that amongst the Enemy those in the rear would direct their fire against whoever fired in front, and they would destroy each other.

General Grey’s orders were clear, concise, and cruel, and they were to be followed blindly. For a general to command his troops to not use their ammunition during a battle sounds ludicrous, but it turned out to be an extremely effective tactic. Not only were the majority of the American troops sleeping, but because musket shots weren’t giving away the British’s position, the Americans could not see to defend themselves. One wave of British troops after the other swept through the American encampment, stabbing and slicing the troops to shreds. The Americans had little to no organization at the time, and could not be sure that those whom they fired at were truly the enemy.

General Charles Grey’s plans worked exceptionally well. The British were like ghosts in the night, and the Americans were like sitting ducks. The Redcoats not only had the element of surprise, but whenever the Americans fired their muskets, they gave away their exact position. American soldiers suffered waves of sharp swords and pounding bayonets, blow after blow. The account of one Hessian soldier, found in The History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, states that, “We killed three hundred of the rebels with the bayonet. I stuck them myself like so many pigs, one after the other, until the blood ran out of the touch hole of my musket.”

Although this Hessian solder’s victim wasn’t so lucky, a majority of the American troops actually survived the British’s surprise attack. However, many of them had life-threatening wounds. Drum Major Daniel St. Clair was the perfect example of a victim of the Paoli Massacre who was critically injured. His wounds, as described in The Battle of Paoli, shed great light on the use of swords in the massacre. Daniel St. Clair lost his left eye and all of the fingers on his left hand, suggesting that he was on the ground warding off an attacking swordsman on horseback. His only form of defense was putting his hand up to shield his face from the sword. The British had no problems attacking defenseless men with their swords and bayonets.

Some would say that the “Battle” of Paoli truly should not be referred to as a battle, but instead, a merciless massacre. According to an article in The Journal of Military History, some British soldiers abhorred the idea of strictly using bayonets and swords. Particularly, British Colonel Charles Stuart went as far as to regard the action at Paoli as murder rather than war. Just reading a few of the statements made about the Paoli Massacre, truly shows that this “battle” was simply barbaric. As one American survivor witnessed, “they (the British) had with fixed bayonets formed a cordon round him, and...every one of them in sport had indulged their brutal ferocity by stabbing him in different parts of his body and limbs.” On the other hand, many of the British actually saw the Paoli Massacre simply as another battle in the Revolutionary War, and even applauded General Grey for ordering his troops to strictly use their bayonets or swords.

The book Final Years of the American Revolution lists 53 American deaths, 150 American wounded, and 71 American captives during the Battle of Paoli. These numbers do not seem too drastic, but compared to the British losses, they were. According to Michael Schaffer’s article “Redcoats’ Ruthless Assault: Night Bayonet Attack Sent Americans Reeling,” the British suffered only a handful of casualties. Not only was the battle itself demoralizing to the American cause, but the events that ensued after the Paoli Massacre were extremely detrimental as well. Charges were filed against General Anthony Wayne for possibly being informed of a potential British attack and not doing anything about it. However, the General was later acquitted of these charges. As Charles Stille writes in his book, Major-General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army,

The court-martial was unanimously of opinion that General Wayne was “not guilty of the charge exhibited against him, but that he, on the night of the 20th of September last, did every duty that can be expected from an active, brave and vigilant officer, under the orders which he then had. The Court do acquit him with the highest honor.”

The controversy surrounding General Anthony Wayne wasn’t even the worst consequence of the Paoli Massacre. Shortly after the British victory at Paoli, they took control of America’s capital, Philadelphia. This was perhaps the worst possible thing that could have happened to the American troops. According to the Independence Hall Association’s timeline, General George Washington then somehow survived a horrid winter in Valley Forge and fought four more years of winning and losing battles before Britain finally surrendered on October 19, 1781. Had there been more casualties at the Battle of Paoli and General Anthony Wayne had not been exonerated of the charges brought against him, the Revolutionary War quite possibly could have had a different ending.

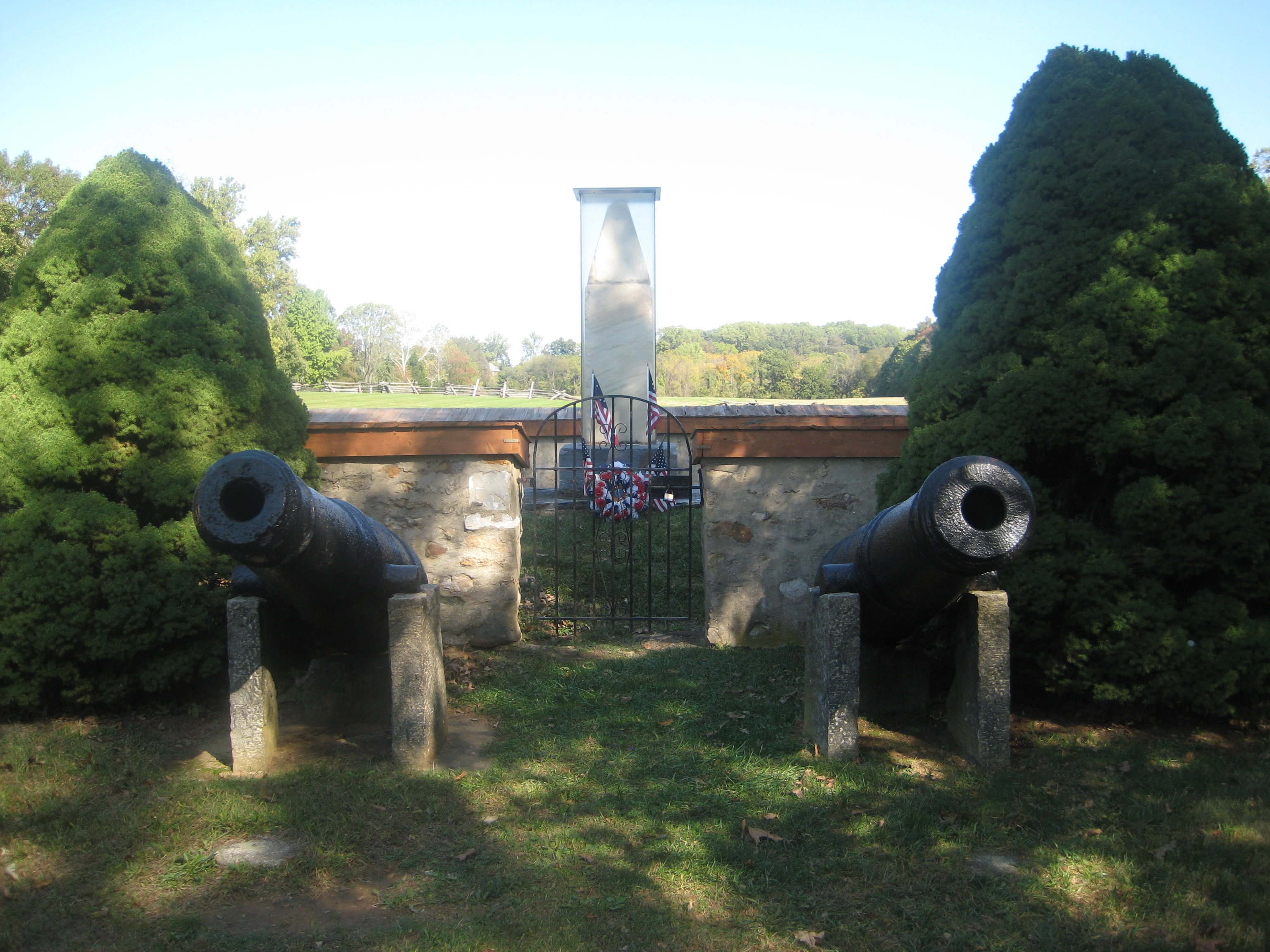

When walking through Memorial Park in Malvern, it is hard to believe that so many American men lost their lives over 230 years ago at that very site. On a typical summer day little kids play baseball at the nearby ballparks, joggers run through the trails of the woods, and plenty of people walk their dogs right by the memorial that was erected 100 years after the battle. Malvern Preparatory School even uses part of the battle site for their cross country team’s races. Each year there is a reenactment commemorating the battle, as well as a Memorial Day parade that most of members of the community participate in. When driving through the borough it isn’t even uncommon to see a car with a bumper sticker that reads, “Remember Paoli.” Although it was once the site of a horrible massacre, the battlefield is now a place of tranquility. The Paoli Massacre will always be remembered not necessarily for the atrocities that occurred that day, but for the fact that many young men gave their lives fighting for our freedom.

Sources:

- “Revolutionary War.” Encyclopedia of American Studies. Ed. Miles Orvell. 2010. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP. 27 2010, <http://eas-ref.press.jhu.edu/view?aid=587>.

- McGuire, Thomas J. Battle of Paoli. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000. 80-110.

- The Philadelphia Campaign 1777: Paoli Massacre. Independence Hall Association, 4 July 1995. 1 Oct. 2010. <http://www.ushistory.org/march/phila/paoli.htm>.

- Smith Futhey, J., and Gilbert Cope. History of Chester County Pennsylvania. Vol. 1. Berwyn Heights, MD: Heritage Books, 2007. 86.

- Starkey, Armstrong. “Paoli to Stony Point: Military ethics and weaponry during the American Revolution.” The Journal of Military History 58.1 (1994): 7.

- Wade, Linda R. Final Years of the American Revolution. Edina, MN: ABDO Publishing Company, 2001. 11.

- Schaffer, Michael D. “Redcoats’ ruthless assault: Night bayonet attack sent Americans reeling.” The Philadelphia Inquirer 15 Sept. 2002. 1 Oct. 2010 <http://www.11thpa.org/elk_news_4.html>.

- Stille, Charles J. Major-General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1893. 88.