On October 27, 1998, President Bill Clinton signed Public Law 105-298, also known as the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998. The new law increased the duration of currently copyrighted works by 20 years. Opponents of the law called it “the Mickey Mouse Protection Act,” because the Walt Disney company had lobbied in favor of the law, which extended copyright on their famous mouse just as it was about to enter public domain. Later, the constitutionality of the act was brought before the Supreme Court, and in 2003 the Sonny Bono Copyright Extension Act was deemed constitutional by a vote of seven to two. With the implementation of the act, copyright now lasts 70 years after the death of an author, and automatically protects an original work the moment it is created.

According to Copyright Basics,copyright is defined as “a form of protection provided by the laws of the United States…to the authors of ‘original works of authorship,’ including literary, dramatic, musical, artistic, and certain other intellectual works.” If it can be copied or imitated, it is protected by copyright laws, except in cases of parody or satire. This is the reason that parodists, such as Weird Al Yankovic and Richard Cheese, are able to satirize works without legal consequences. In fact, the copyright laws of today would seem alien to someone who lived centuries ago. It has been a little over two hundred years since Pennsylvania passed its first copyright act while it was still home to the United States capital, Philadelphia.

In 1783, Congress recommended that all states of the Union should pass laws protecting the copyright of an author’s work. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania took the advice, and on March 15, 1784, during the second sitting of the eighth General Assembly, the act was passed. This made Pennsylvania the seventh state to delve into the world of copyright law.

From its very inception, copyright law was a highly debated issue. Thomas Jefferson wrote to Brick Barn Plantation owner Isaac McPherson: “Stable ownership is the gift of social law, and is given late in the progress of society. It would be curious then, if an idea, the fugitive fermentation of an individual brain, could, of natural right, be claimed in exclusive and stable property.” Jefferson, later in the letter, referred to such a “monopoly” over an idea as an embarrassment to society that may outweigh its benefits, citing the fact that nations without copyright laws have just as much creative output as those that do. But if copyright law is an “embarrassment” to the public, and if it is not an innate right, then why consider the law in the first place?

Before the internet, copying-and-pasting, and file-sharing there was still theft of intellectual property. The invention of the printing press allowed the relatively rapid creation of books for sale to the public, but nothing prevented it from being used to copy someone else. The problem Pennsylvania’s initial copyright law was intended to fix was the production of an author’s work without his consent.

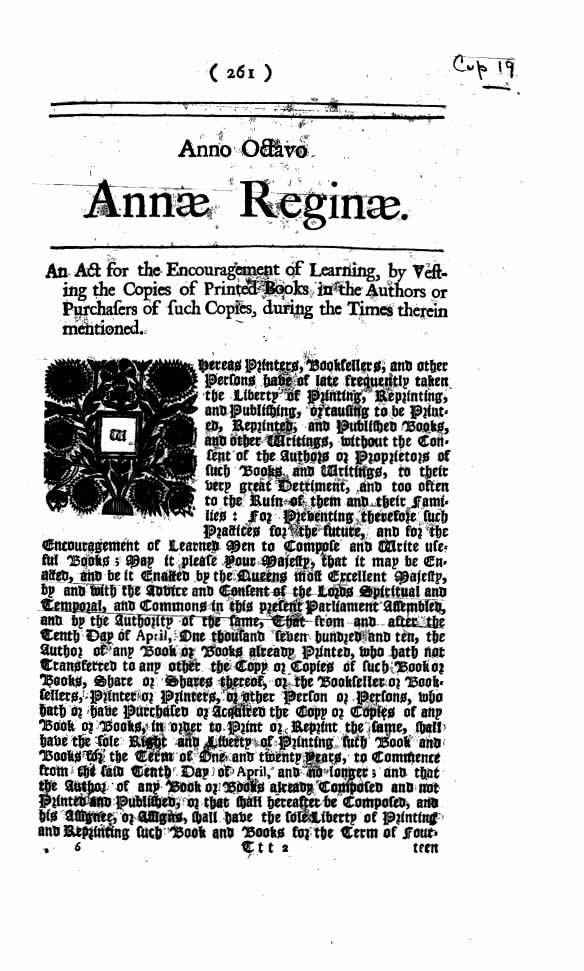

Great Britain had suffered from printing press abuse and had passed a copyright law for similar reasons decades earlier called the Statute of Anne. The British act stated it sought to eliminate the production of “books and other writings without consent of the author or proprietors of such books and writings, to their very great detriment and to the damage of their families.” In other words, the act was created to combat the potential monetary loss an author faced because of those who copied and distributed his work for their own gain.

The practice of pirating British works was so popular that according to Professor Karen VanSpanckeren, writer of Outline of American Literature, early American writing was stunted for decades. Publishers preferred pirating the British texts over printing the works of unproven American authors because there was more money to be made.

While Pennsylvania and other states were testing out copyright, the United States Congress decided it was time to do the same. In 1787, just three years after Pennsylvania’s first copyright law, the Constitution was adopted; from it, came the basis of all federal copyright law. Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8 of the Constitution grants the power, “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” Though many, Thomas Jefferson included, opposed it, the United States finally had copyright law.

In The Federalist No. 43, one in a series of articles and essays justifying ratification of the proposed Constitution, James Madison wrote of the copyright clause, “The utility of this power will scarcely be questioned…The public good fully coincides in both cases [of authors and inventors], with the claims of individuals.” Madison saw no issues with copyright law; it benefited authors by giving them a protected source of income and it benefited the public by encouraging those authors to write more books.

While the Constitution had made it clear that copyright was the federal government’s duty, it was never particularly specific about how to grant it. There needed to be actual laws passed to clarify this. In 1790, in the United States capital of Philadelphia, the first federal copyright law, “An act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned,” was enacted: national copyright law was born.

Obtaining copyright protection on a work required a multitude of steps, making it highly time consuming. Many works were never protected simply because their authors did not wish to go through the lengthy procedure or made some mistake in the process. First, the author had to send a copy of the title of his work to the clerk’s office of the district court where the author lived. The clerk was to record, in a very specific format, the deposit of this title. Within two months of the deposit, the author had to have an advertisement of the record posted in a newspaper for at least four weeks.

Within six months of the work being published a copy had to be sent to the Secretary of State. A later amendment to the law required that a full copy of the record be on the title page or after the title page. But the whole copyright protection process was not free. The registration services of the clerk’s office, the posting of a newspaper article for nearly a month, and the sending out of a copy of the book all cost money.

After the work of observing the formalities imposed by the federal government, paying the fees, and waiting for everything to check out, a work was protected for a mere fourteen years. The act allowed a further fourteen years of protection if the author was still alive, but only if the process was repeated once more.

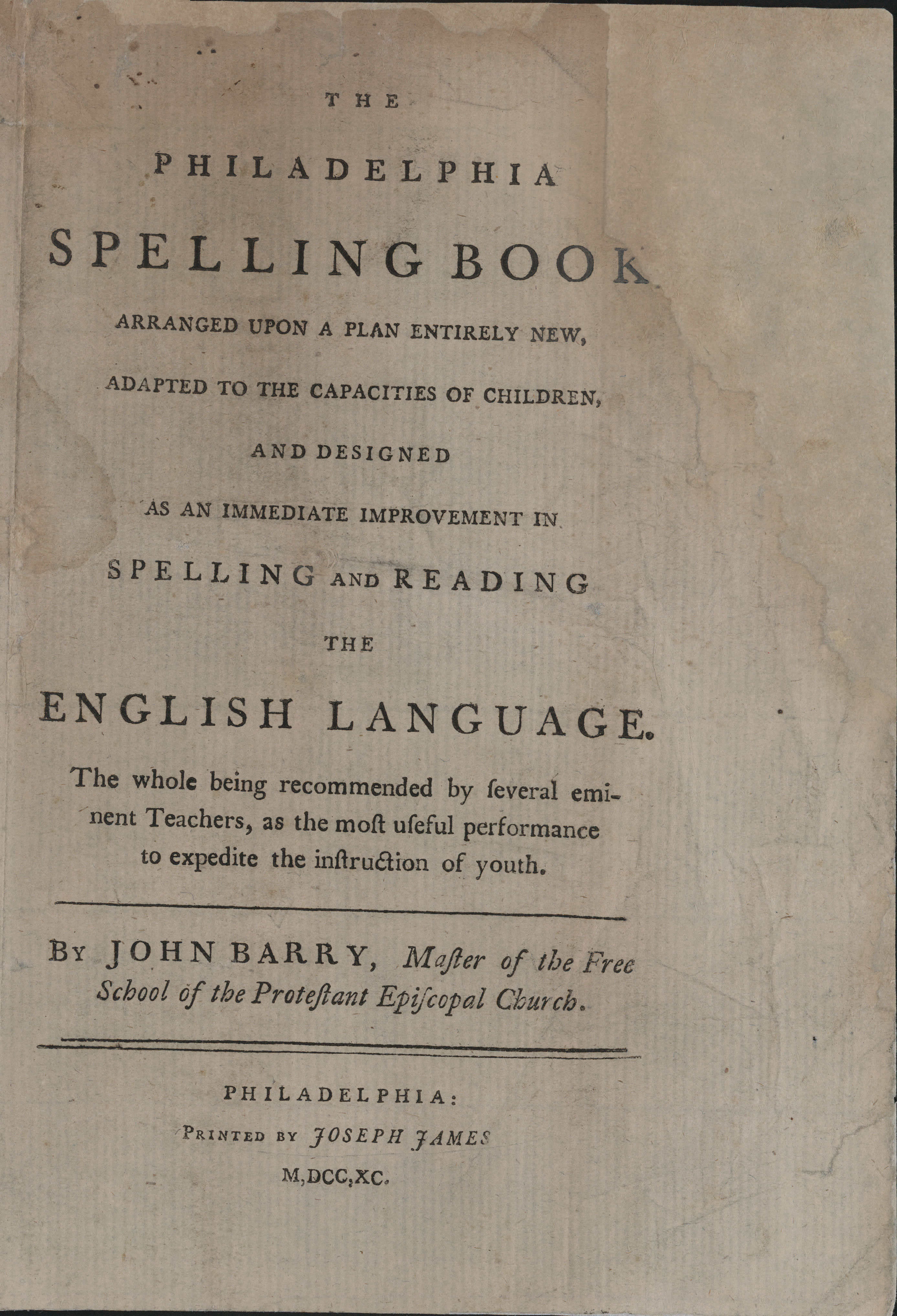

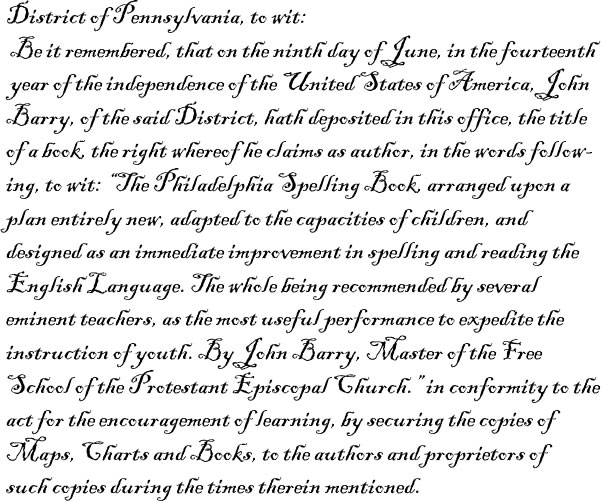

Also in 1790, Sam Caldwell, the clerk of the District of Pennsylvania, recorded the registration of The Philadelphia Spelling Book. This was a historic event because it was the first book to be protected under federal copyright law in the United States, essentially making Pennsylvania the birthplace of all copyright law:

It is impressive how quickly John Barry, the book’s author, took advantage of the new law considering the procedure it required.

In The Federalist No. 43, James Madison noted that, “The States cannot separately make effectual provision for either of the cases [of authors and inventors], and most of them have anticipated the decision of this point, by laws passed at the instance of Congress.” Though Madison felt no need to explain why state law was insufficient, the flaw in non-federal copyright law is easy to spot: it does not apply outside the state.

Pennsylvania’s law attempted to account for this glaring loophole with its final section, which says, “Provided nevertheless, That this act shall not take place until such time as all and every of the States of the Union shall have passed laws similar to the same, in conformity with the recommendation of Congress.” Though not foolproof, this provision delayed the law until all other states passed similar ones in the hope that they did not conflict seriously.

Despite the obvious advantage of federal copyright law, some state laws offered protection that it did not, such as for unpublished works, and it wasn’t until the Copyright Act of 1976 that federal laws provided similar protection. The 1976 law also preempted all prior copyright law, including state law, resolving the issue of state versus federal copyright. But just as the scope of state law was insufficient, even national law might conflict with that of other nations.

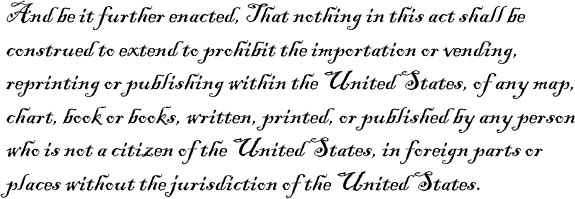

The Copyright Act of 1790 went as far as including an entire section to resolve any question of the United States’ stance on international piracy,

As time went on copyright law in the United States became more powerful, covering more types of works. It slowly became longer lasting, easier to apply, and friendlier to non-Americans Listed are the numerous additions and changes that have been made to copyright law:

- 1802, prints were added to maps, books, and charts as works that could receive copyright.

- 1831, music was added.

- 1865, dramatic compositions were protected as well as photographs and their negatives.

- 1870, works of art were protected and registration was centralized, while translations and dramatizations were allowed.

- 1891, copyright relations with foreign nations were authorized.

- 1897, music became protected against public performance.

- 1909, the extension term was doubled to 28 years, and certain unpublished works were protected.

- 1912, motion pictures became protected.

- 1914, the United States joined the Buenos Aires Copyright Convention of 1910, establishing copyright between the United States and certain Latin American nations.

- 1953, recording and performing rights were extended to non-dramatic literary works.

- 1978, protection had come to last 50 years beyond the life of the author, the United States was a member of the Universal Copyright Convention, certain sound recordings were protected, and prior law was modernized.

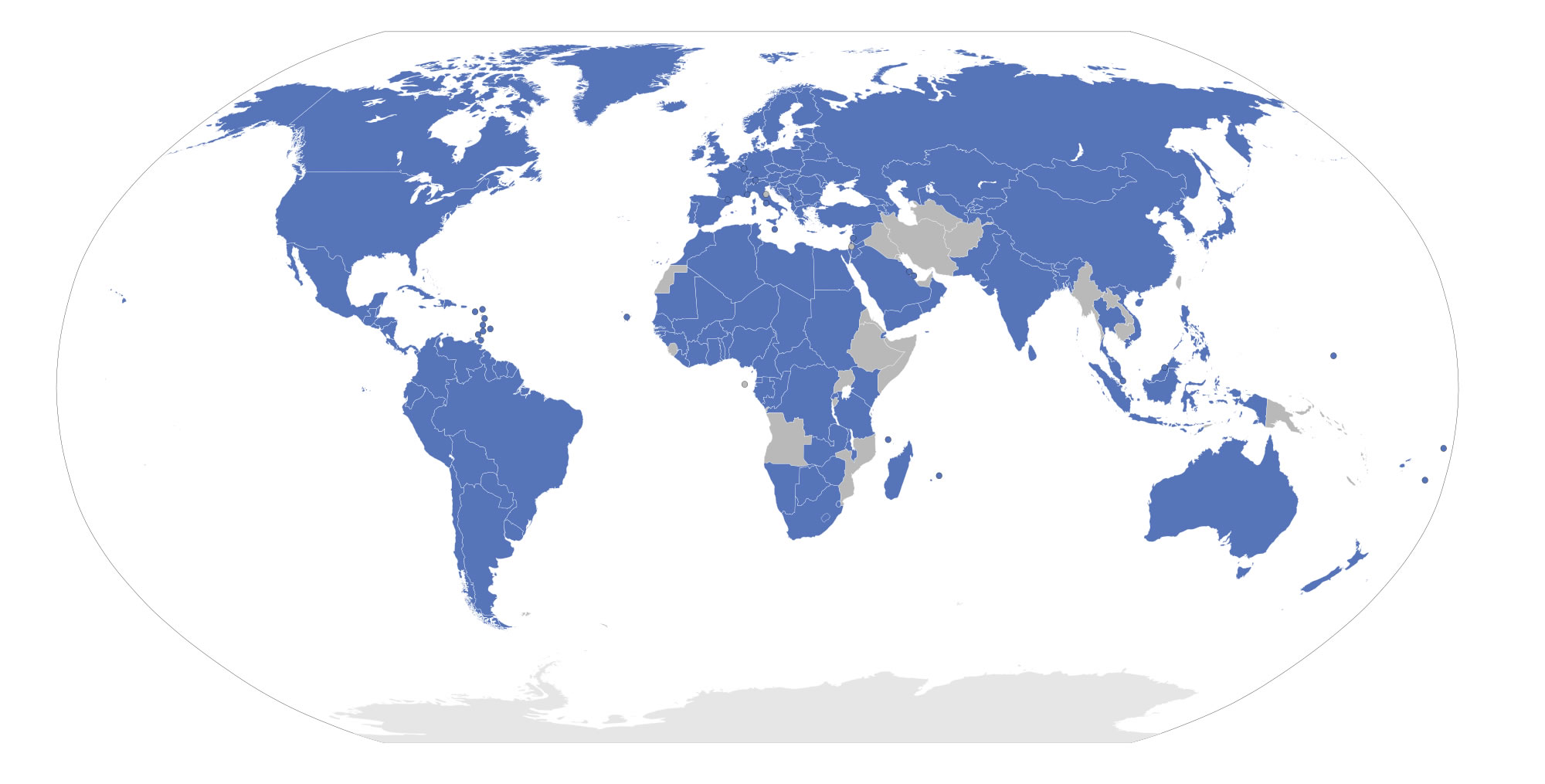

- 1989, the United States fully met the standards of the Bern Convention, the primary international treaty on copyright

- 1990, the law was amended to include computer programs and sound recordings, along with architectural and mask works. The same year, it was decided that the copyright symbol was no longer necessary.

- 1998, the duration of U.S. Copyright protection came to match that of most European nations

- 2008, renewal was automatic and the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act extended the length of copyright protection to last until 70 years after an individual’s death.

Today, copyright registration can be done online or by submitting forms to the United States Copyright Office in Washington, DC. The author or inventor must choose between five different categories to submit their work under: literary, visual arts, performing arts, sound recordings, or single serials. While the copyright registration procedure is quite simple today, it does not mean that all works are fully protected. As stated before, the original purpose of copyright law was to protect literary works, but with the advancement of technology, the law has come to encompass various different works that must be protected from piracy.

Although copyright law has come a long way, there is still a great deal of confusion over what is covered and what is not. In 2009, J.D. Salinger, now deceased, sued Swedish author, Fredrik Colting, for writing a novel containing a version of the American author’s character, Holden Caulfield, from The Catcher and the Rye. In the end, Salinger won, and the book was banned from being advertised and distributed in the United States. Though the character’s name was not the same, and Colting thought his own work was protected because it was intended as a “parody,” the judge ruled that the character was too similar to Holden. It is apparent that characters, even their personalities, can be protected under copyright law.

Perhaps the most confusing provision of copyright law is “public domain.” Many people have trouble distinguishing between what is free to be used and what is not. For example, works generated before 1923 usually fall into the realm of public domain because of copyright expiration. This means that people can copy and distribute the work without repercussions. Government documents are also considered available for distribution without penalty because they are in the public domain of the United States. But the confusion continues because if a work was published without the copyright symbol between 1923 and 1977, it is also considered to be in public domain.

Although literary piracy has been present for centuries, with the evolution of technology, the most pirated works in recent are music and films. This is mostly because of the creation of the World Wide Web and “file-sharing.” Anyone can upload a movie or song onto the internet and distribute it to others. Because of this, those who generated the work lose money because no one is buying the material they have produced, and modern society has done nothing but perpetuate it, especially through the use of file-sharing, or “the practice of or ability to transmit files from one computer to another over a network or the Internet.”

Napster, created in 1999 by Shawn and John Fanning, was such a network. It was created as a peer-to-peer file-sharing network where people could share audio files with their friends and family. Unfortunately for the Fannings, the website caught the attention of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), which filed a lawsuit.

The creators of Napster claimed to have been under the impression that they were within their rights to distribute the material because the files fell under the “fair use,” another confusing provision of copyright law. Regrettably for Shawn and John Fanning, they were wrong. Because the material was not being given out for educational and nonprofit purposes, as well as the fact that the illegal act served to damage the potential music market, the Fannings were found in violation of the United States Copyright Law. In the end, the duo agreed to pay a settlement of $36 million.

James Madison could scarcely have imagined the breadth of intellectual material produced today. The “Father of the Constitution” had no way of foreseeing the coming of an astounding informational and technological age. Compared to the former president’s era, things have changed drastically. With such advancements, the protection of intellectual property, such as music, art, and films, becomes exponentially more important because of the ease of piracy. Thankfully, authors and inventors alike can breathe easier knowing that the U.S. Copyright Law exists to protect their work to the best of its ability. Perhaps one day it will be able to stop any and all piracy.

Sources:

- Chan, Sewell. “Judge Rules for J.D. Salinger in ‘Catcher’ Copyright Suit.” The New York Times. The New York Times Company, 1 July 2009. May 2011. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/02/books/02salinger.html>.

- Cong. Rec. 7 Oct. 1998: 3831-5 H9725-H100121.

- “Copyright Basics.” Copyright: United States Copyright Office. U.S. Copyright Office, 2008. May 2011. <http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ1.pdf>.

- “Copyright Law of the United States and Related Laws Contained in Title 17 of the United States Code.” Copyright: United States Copyright Office. U.S. Copyright Office, 2008. May 2011 <http://www.copyright.gov/title17/circ92.pdf>.

- “Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States.” Cornell University: Copyright Information Center. Cornell Copyright Information Center, Jan. 2011. Web. May 2011. <http://copyright.cornell.edu/resources/publicdomain.cfm>.

- “File-Sharing.” Encyclopedia.com. HighBeam™ Research, Inc, 2011. May 2011 <http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O999-filesharing.html>.

- Gilreath, James. “American Literature, Public Policy and the Copyright Laws before 1800.” in Federal Copyright Records, 1790-1800. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1987. xv-xxv.

- Jefferson, Thomas. Letter to Isaac McPherson. 13 Aug. 1813. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. Ed. Albert Ellery Bergh. Vol. 13-14. Washington: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association.

- Kurland, Philip B. and Ralph Lerner. The Founders’ Constitution. University of Chicago, 2000. 13 Oct. 2010. <http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/tocs/toc.html>.

- Madison, James. “The Federalist No. 43.” The Federalist. Ed. Jacob E. Cooke. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961.

- RIAA. “Who Music Theft Hurts.” RIAA: Recording Industry Association of America. RIAA, 2011. May 2011 <http://www.riaa.com/physicalpiracy.php?content_selector=piracy_details_o....

- Solberg, Thorvald. United States. Library of Congress. Copyright Office. Copyright Enactments of the United States 1783-1906. 2nd ed. Washington: GPO, 1906.

- Story, Joseph. Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States: With a Preliminary Review of the Constitutional History of the Colonies and States, Before the Adoption of the Constitution. Boston: Hilliard, Gray, and Company, 1833.

- “The Copyright Act of 1790.” Copyright: United States Copyright Office. U.S. Copyright Office, 2008. May 2011 <http://www.copyright.gov/history/1790act.pdf>.

- VanSpanckeren, Karen. “Outline of American Literature.” InfoUSA. United States Information Agency, 1999. May 2011. <http://usinfo.org/oal/>.