Oliver Wendell Schenk, 1972

Although the reserved demeanor of most Old Order Amish might suggest otherwise, their history has been indelibly marked by violent persecution and internal strife. A series of difficult choices—whether to stay in Europe or travel to America, whether to assimilate or separate from the larger community, whether certain customs should be honored or adjusted—have shaped the identities of countless sects, including the Old Order Amish, who are perhaps the most distinct to outsiders. An overview of where and how this group ultimately came to be is essential in understanding the customs and values that define them.

The Swiss Anabaptists, forerunners to the Amish and Mennonite traditions, levied one of the earliest and most radical critiques of the religious establishment during the Reformation. They contended that the human institution of the Church, with its elaborate customs and traditions, distracted from the real purpose of Christianity—a simple and humble lifestyle modeled after the example of Jesus Christ.

Their defining break with Church tradition was the practice of adult baptism rather than infant baptism, which Conrad Grebel called, "a senseless, blasphemous abomination of Scripture." Anabaptists such as Grebel felt that only those who were mature enough to understand and make a conscious lifelong commitment to Christian principles should be baptized as Christians. On January 15, 1525, Grebel and others baptized each other in Zürich, despite the threat of persecution by local authorities.

In 1527, in Schleitheim, on the Swiss-German border, representatives of the "Swiss Brethren" met and agreed on the foundational points of the nascent movement, including the baptism of believers as adults, the banning or excommunication of unrepentant sinners from the group, a withdrawal from civic affairs, a refusal to swear oaths, and an attitude of nonviolence. In 1536, Menno Simmons (1496-1561), a former Dutch Catholic priest, joined a northern sect and, due to his early leadership and the influence of his writings, the Anabaptists were soon known as "Mennists" or "Mennonites."

J. Luyken

Library of Congress

The sixteenth century witnessed the diffusion of Mennonites throughout areas of modern Switzerland, Germany, and The Netherlands primarily as a result of persecution. In A History of the Amish People and Their Faith, Norma Fischer-McClearn recounts that the Mennonites were "brought to trial, tortured, branded, dropped from a ladder into a fire, beheaded, garroted, drowned, dismembered, and burned at the stake." They were noted for their incredible unwavering refusal to compromise their beliefs, even in the face of certain death. This impressed many new converts, helping the movement to grow. The Bloody Theater or Martyr's Mirror, first released in 1660, contained over a thousand pages filled with stories of martyrdom and is still one of the most important books in the Amish tradition.

By the 1690s, the continued persecution and dispersal of populations meant that many Mennonite groups became isolated from each other. Although the Dordrecht Confession of 1632 established the foundational principles of the movement, there were increasing differences in how the rules were interpreted and applied. These disagreements inevitably reached a boiling point in 1693 when Jacob Amman, a young Alsatian Mennonite Bishop, traveled around Switzerland preaching a strict interpretation of Mennonite traditions.

Amman supported the use of shunning (Meidung) to maintain a community of true believers. This practice was intended to lure back those who had strayed from the church or had been excommunicated and it created a clear barrier between the congregation and the rest of society. Shunning, although specifically mentioned in early Anabaptist and Mennonite documents, had been regarded by most as a symbolic gesture that was not to be enforced literally. Many Swiss Bishops like Hans Reist felt that literally practicing shunning would be unchristian and would drive those who had left the group even further away.

When Reist refused to meet with Amman to discuss shunning in 1694, Amman promptly excommunicated him and any other Bishops and congregations who would not agree with this practice. In addition to endorsing a strict form of shunning, the groups that sided with Amman distinguished themselves with more conservative dress and grooming styles and by practicing ceremonial foot-washing at communion services. In 1699, Amman and his followers attempted to reconcile with Reist's group but, after a decade or so, it was clear that the split would not be mended. Those who sided with Amman were eventually known as the Amish.

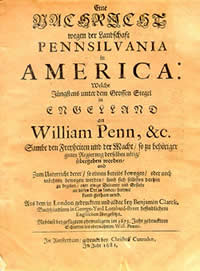

to Pennsylvania for religious freedom.

The prospect of starting fresh in the New World was attractive to many Amish and Mennonites as they faced relentless persecution into the early eighteenth century. One area of the New World that held a particular attraction for these groups was Pennsylvania, where William Penn, a Quaker, was encouraging other religious groups to immigrate and take part in his "holy experiment." A few Mennonites had already come to Pennsylvania by the 1680s, mostly settling in Germantown. The first Amish settlement in Pennsylvania was in Oley Township, Berks County, founded in 1714.

The first significant wave of Amish immigration to North America began in 1737 when the ship Charming Nancy set sail for North America with twenty-one Amish families aboard. While a trans-Atlantic journey could be an extreme hardship at that time and living conditions in colonial Pennsylvania were tough, many Amish also found a bountiful landscape and tolerant authorities in their new home. Positive reports about the potential of the local soils and the friendliness of the people encouraged about 500 adults to emigrate to Pennsylvania before 1770.

of first Amish community.

Some of the significant early Amish settlements included Northkill Creek (present-day Tilden, Upper Bern, Centre, and Penn townships) and Irish Creek in Berks County and the Old Conestoga settlement (present-day Manheim and Upper Leacock townships) in Lancaster County. The first prominent Bishop to move to Pennsylvania was Jacob Hertzler (1703-1786), who moved to Northkill Creek in 1749. By the American Revolution, there were at least eight Amish settlements in Pennsylvania and by the end of the eighteenth century the population had expanded into Somerset and Mifflin counties.

In 1815, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the second wave of Amish immigration into the United States began. Many of the European Amish passed through the settlements in Berks and Lancaster counties and received aid from community members, but they rarely settled in these areas, instead choosing locations such as Ohio, Iowa, Indiana, New York, and Ontario.

The Amish in America tended to be more strict and traditional than their European counterparts, probably because the Europeans had been under more pressure to assimilate into the surrounding culture. The strict observance of shunning, the eschewing of "worldly" fashions, and a well-defined separation from civic society among the Pennsylvania Amish were reaffirmed in meetings held in 1809 and 1837. These are often called the "Pennsylvania Disciplines."

As the second great wave of immigration came to a close in the 1860s, disagreements over the interpretation of certain basic rules came to the fore, as they had nearly two centuries earlier. Progressive sects, many composed of recent immigrants, had become more relaxed in enforcing prohibitions on fancy clothing, higher education, the use of meetinghouses for services, the use of certain technologies, and involvement in civic life. Another issue that had become increasing problematic, particularly among the Amish in Mifflin County, was stream baptism. Baptizing outdoors, in running water, was a break with traditional home baptism ceremonies.

Stream baptism was one of a host of issues that signaled clear divisions within the national body of Amish. Ministers' meetings (Diener-Versammlungen) were called to try to restore unity between the arguing factions. The first of these annual meetings was held in 1862. From the start, the conservative factions felt under-represented and, with tensions exacerbated by the meetings, they stopped attending after 1865. This foreshadowed many future splits that resulted from different opinions over what amount of participation in the larger society was acceptable.

The conservative factions become known as the Old Order Amish because they supported a strict adherence to the traditional rules (Ordnung) of the community. Collectively, the more progressive groups were known as the Amish Mennonites. During the 1920s, the various remaining Amish Mennonite groups merged with the Mennonites.

The twentieth and twenty-first centuries have been a period of relative growth and prosperity for the Old Order Amish. From the perspective of American society, interest in the Amish has risen gradually with an accompanying increase in tourism to Amish areas. While the attention has not always been positive, with a controversy over Amish schooling that lasted several decades as a prime example, the overall trend has been towards a more sympathetic interpretation of Amish values and the Amish lifestyle by the general public.

Sources:

- Buck, Roy C. "Boundary Maintenance Revisited: Tourist Experience in an Old Order Amish Community." Rural Sociology. 43, 2 (1978): 221-234.

- Hostetler, John A., ed. Amish Roots: A Treasury of History, Wisdom, and Lore. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

- ______________. Amish Society, Fourth Edition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

- Hostetler, John A. and Gertrude Enders Huntington. Amish Children: Education in the Family, School, and Community, Second Edition. Fort Worth, Tex.: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992.

- Kraybill, Donald B. The Riddle of Amish Culture, Revised Edition. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- _______________. "Negotiating with Caesar." The Amish and the State, Second Edition. Ed. Donald B. Kraybill. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. 3-22.

- Nolt, Steven M. A History of the Amish. Intercourse, Pa.: Good Books, 1993.

- The Pennsylvania Dutch Tourist Bureau, comp. and ed. Pennsylvania Dutch Guide Book. Lancaster: The Pennsylvania Dutch Tourist Bureau, 1959.

- Weaver-Zercher, David. The Amish in the American Imagination. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- Yoder, Paton. "The Amish View of the State." The Amish and the State, Second Edition. Ed. Donald B. Kraybill. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2003. 23-42.