In early August 1793, lodgers at the North Water Street boardinghouse of Richard Denny fell violently ill. Within days, four boarders and two workers perished after experiencing high fevers, seizure attacks, episodes of vomiting black bilious substances, and jaundiced skin. Those dead at the Denny boardinghouse were the earliest recorded cases of the 1793 Philadelphia Yellow Fever epidemic. Between August and November 1793, yellow fever upended the United States’ temporary capital, bringing commerce to a halt, crippling the city’s government, and killing over 5,000 of the city’s 50,000 inhabitants.

We know today that yellow fever is a virus that belongs to a subset called flaviviruses, which includes other diseases such as West Nile virus and dengue fever. The virus spreads through the human bloodstream via bites from infected mosquitos. Though rare in the United States, yellow fever still exists, especially in Africa and Central and South America. There is a vaccine for yellow fever, but there is no known cure. In 1793, doctors and scientists in Philadelphia did not understand the causes of yellow fever, and this lack of knowledge resulted in confusion and thousands of deaths during the summer and autumn of 1793.

The earliest cases of yellow fever appeared around Water Street. Running parallel to the Delaware River, Water Street was a muddy, narrow lane, no wider than thirty feet, hemmed in on the east by the city’s wharves and on the west by a high embankment. Isaac Weld, an Irish writer who visited Philadelphia in 1795, described Water Street as a cramped space "with the air very confined," with "stenches … owing in part to the quantity of filth and dirt that is suffered to remain on the pavement" amid puddles of stagnant rain and river water. Water Street’s residents consisted primarily of poor laborers who worked at the city’s docks, sailors, and recent immigrants, a segment of the city rarely cared for by Philadelphia’s medical elite. By mid-August, however, the fever had spread beyond Water Street to wealthier Philadelphians where it came to the attention of esteemed doctors such as John Foulke, Hugh Hodges, and Benjamin Rush. After treating a number of cases, the three met on August 19, 1793, and agreed that they were witnessing an outbreak of the 'bilious remitting yellow fever' in Philadelphia for the first time since 1762.

Physicians readily agreed on the symptoms that characterized yellow fever. William Currie, one of the founders of Philadelphia's College of Physicians, described how patients first experienced weakness, chills, headaches, and shortness of breath, followed by frequent vomiting. After three or four days, the symptoms normally diminished. For many survivors, this proved the end of the disease. For others, however, the fever quickly returned, bringing "frequent vomiting of matter resembling coffee grounds in color and consistence," which was stale blood hemorrhaged in the stomach. According to William Currie, patients took on "a cadaverous appearance … succeeded by a deep yellow or leaden colour of the skin and nails" that gave the disease its name. Lastly, they became incontinent and lost consciousness, oftentimes bleeding from the eyes and nose, until they died. In all, the disease took a little more than a week to run its course.

The American Philosophical Society's Philosophical Hall, image courtesy of the American Philopsophical Society

In 1793, the College of Physicians met on the second floor of Philosophical Hall, located at the corner of 5th and Chestnut Streets, to discuss responses to the yellow fever epidemic.

Medical professionals could not, however, agree on the cause of the disease. Climatists, such as Benjamin Rush, believed that the source of the fever lay in the atmosphere of the city. According to climatists, corrupted or polluted air from crowded and unclean conditions in the city brought on the disease. Rush suggested that a large cargo of rotting coffee, carried on a ship from the Caribbean French colony San Domingue (present-day Haiti) and deposited just a block away from Water Street, could be the origin of the fever. Other medical professionals, many of them members of the College of Physicians, subscribed to contagionism, a belief that yellow fever was caused by specific infectious elements passed from person to person. Throughout the summer of 1793, refugees fleeing the slave revolution in the French colony San Domingue had arrived in Philadelphia, and many contagionists viewed them as the clear source of the infection. The disagreement between contagionists and climatists quickly grew heated as it mixed with xenophobia and political disagreements. When the College of Physicians met at the American Philosophical Society’s headquarters at Fifth and Walnut Streets, they issued a report that attempted to bridge this heated debate by recommending the diseased be quarantined and the city streets cleaned.

Neither contagionists nor climatists understood the virology of yellow fever, though both were correct in recognizing that the disease developed due to an infectious agent and environmental factors. Part of a wider transatlantic yellow fever pandemic that occurred between 1791 and 1805, Philadelphia’s 1793 yellow fever epidemic was the consequence of centuries of social and demographic changes occurring around the Atlantic world. Yellow fever originated in east and central Africa, where indigenous female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes carried the virus. When infected mosquitos bit humans, they transmitted the yellow fever virus into the person’s blood. Aedes aegypti required wet and warm climates to survive. They also bred and laid eggs in water vessels such as cisterns or barrels as opposed to swamps, which allowed them to survive and multiply on long sea voyages. Carried on one of the hundreds of slave ships departing Africa, Aedes aegypti brought yellow fever to the Americas, where it became a frequent scourge among the dense populations and marshes of Caribbean plantations. From there, Aedes agypti and the yellow fever virus they carried could be brought as far away as Quebec or Scotland on ships bringing people and goods around the Atlantic.

Aedis Aegypti mosquito, photograph by Muhammad Mahdi Karim, courtesy Wikipedia

Female Aedis aegypti mosquitos, common to tropical and subtropical regions in Africa and the Americas, spread the yellow fever to humans when they bite them.

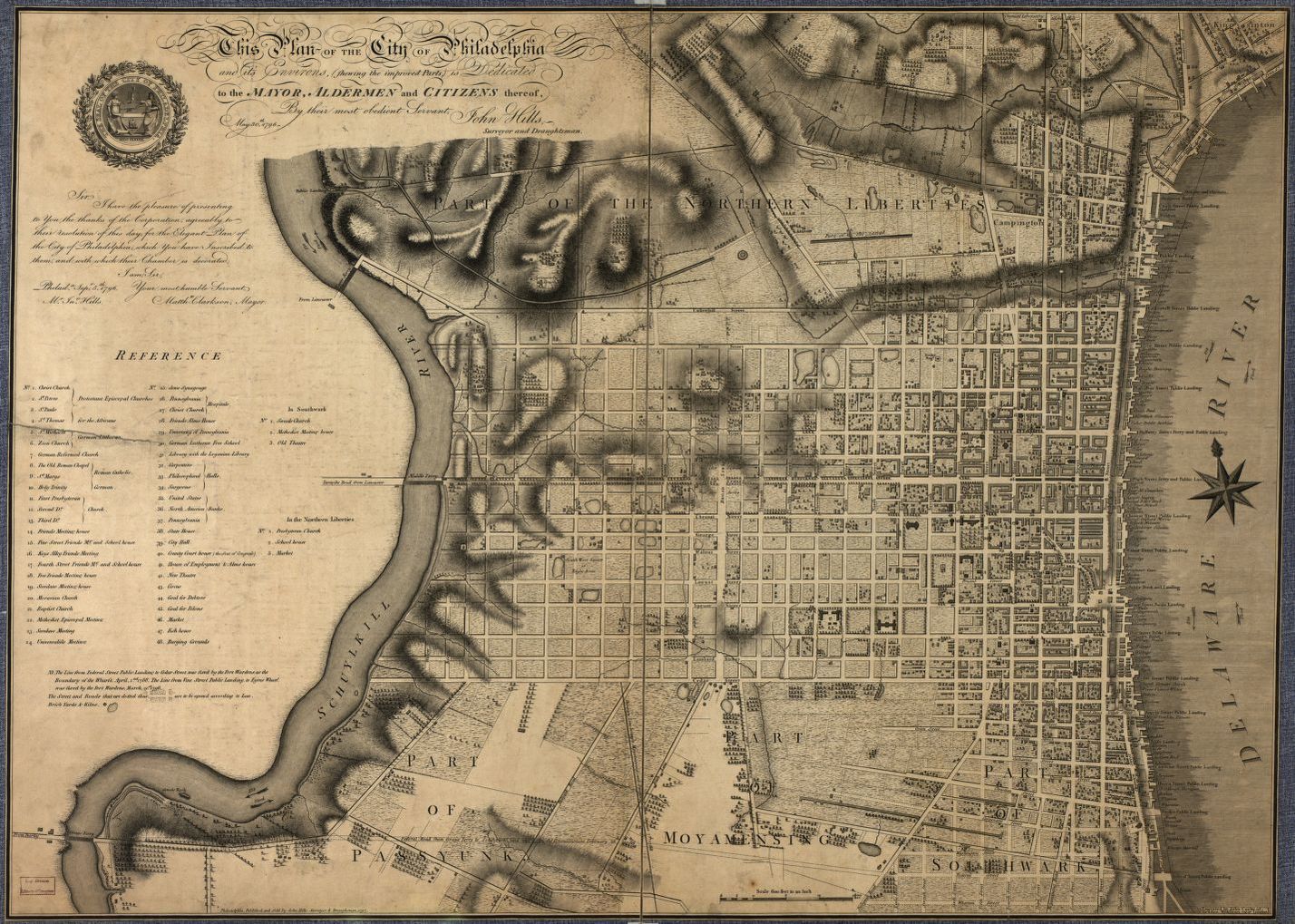

Plan of the City of Philadelphia, map by John Hills, courtesy Library of Congress

In 1793, most of Philadelphia’s population lived within a mile of the Delaware River between the neighborhoods of Northern Liberties and Southwark. This 1797 map still depicts a city with neighborhoods clustered closer to the waterfront, where mosquitoes could easily spread yellow fever among the people of Philadelphia

Philadelphia proved an ideal climate for the spread of yellow fever in the summer of 1793. Almost all of the city’s population lived within a two and a half square mile area along the Delaware River, providing Aedes aegypti mosquitos with plentiful water in which to breed and a closely packed population which the mosquitos could feast upon. The thirty-year gap since the last yellow fever outbreak also meant many Philadephians did not have immunity to the virus. Philadelphia had also witnessed a mild winter and what many residents considered the hottest summer in recent memory. This left behind dried-up stream beds and stagnant puddles where mosquitoes thrived. Many historians believe the yellow fever likely arrived in July from one of the ships bearing refugees from San Domingue, where yellow fever was endemic, though the virus could have been transported from elsewhere. As the largest urban center and busiest port in the United States, Philadelphia welcomed ships year-round that stopped at yellow fever hotbeds around the Atlantic. While no Philadelphians identified mosquitoes as the source of the fever, some in the city noted the high number of mosquitoes during the epidemic. One Philadelphian writing for Dunlap’s American Daily Advertiser noted "a great encrease [sic] of mosquitoes in the city," especially in "rain-water tubs" where he found "millions of the mosquitoes fishing about the waters with great agility."

As newspapers published reports and warnings about the fever, fear quickly spread among the city’s inhabitants. Thousands abandoned Philadelphia during the final week of August, most of them the city’s wealthy who owned homes in the countryside. By the end of the epidemic, over 20,000 Philadelphians had fled, many choosing to find refuge in towns surrounding the city, such as Germantown. Of those who remained in the city, nearly twenty percent died from the disease. Seven out of eight victims belonged to Philadelphia’s working class, impoverished servants and laborers unable to afford the proper medical care, abandon their jobs and leave the city, or quarantine themselves. Without a clear understanding of the fever’s cause, many resorted to unproven preventative measures and folk remedies. Some lit fires on street corners, fired cannons down streets, and burned tobacco in their homes, believing the smoke would cleanse diseased air. Philadelphians also resorted to chewing garlic, convinced of the food’s medicinal powers. Others relied on cleaning themselves and their tools with vinegar in a desperate attempt to protect themselves from the fever.

The sparse and decentralized governing bodies present in Philadelphia—federal, state, and municipal—failed to address the disease. Philadelphia was serving as the temporary capital of the United States, and most federal officials, including President George Washington, had departed the city by early September without providing resources or directions for countering the fever. The state legislature and Governor Thomas Mifflin refused to create a new health office or grant emergency funds for the sick before adjourning and departing the city. They were joined by other municipal officials who similarly abandoned their posts. Institutions intended to aid the poor and sick, such as the Overseers and Guardians of the Poor and the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Sick Poor, refused to treat those with yellow fever out of fear of spreading the disease. Municipal officials also bickered over the handling of quarantining ships coming to Philadelphia, a disagreement exacerbated by the September 6 death of James Hutchinson, Philadelphia’s port physician, from yellow fever. Philadelphia’s mayor Matthew Clarkson found himself forced to rely on a committee of twenty-six community volunteers to furnish medical care for the sick, bury the dead, and provide relief to those who remained in the city.

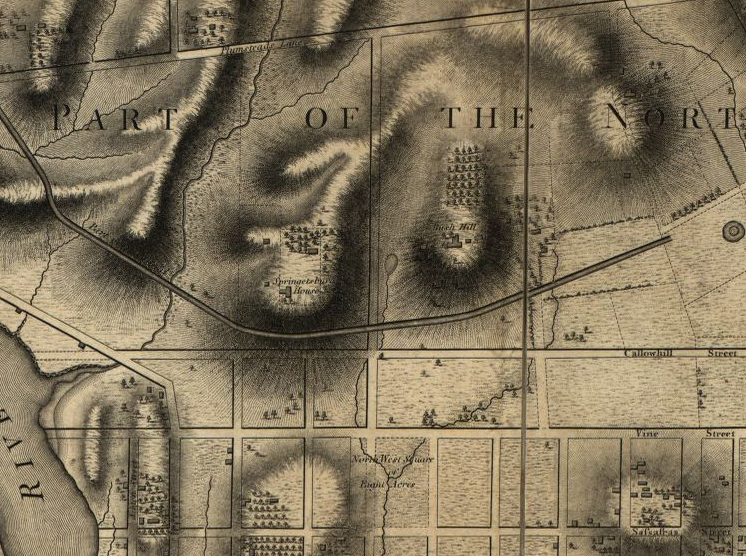

Bush Hill on the Outskirts of Philadelphia, Plan of the City of Philadelphia, map by John Hills, courtesy Library of Congress

This 1797 map of Philadelphia includes the location of Bush Hill. Philadelphia’s remaining leaders chose to use the mansion as a hospital for its size and location far from the center of the city.

In need of a hospital dedicated to yellow fever patients, Mayor Clarkson directed the remaining Guardians of the Poor to use Bush Hill Mansion, located just north of the city near what is now Matthias Baldwin Park, for use as a hospital. Bush Hill’s owner had been away on an extended trip to England, allowing the empty mansion to be quickly converted into a hospital. French-born merchant Stephen Girard, accompanied by a German-born cooper named Peter Helm, volunteered to manage the hospital. Girard hired refugee doctor Jean Devèze who had extensive experience treating the disease in San Domingue. Devèze did not believe the fever was contagious and recommended gentle medicines intended to strengthen the body’s systems. With a staff of nurses and apothecaries, Devèze prescribed stimulants, quinine, cordials, tonics, and frequent cold baths. By October the medical staff at Bush Hill had established an efficient hospital that succeeded in treating scores of sick Philadelphians. Still, half of those admitted succumbed to the disease, in part due to many patients being admitted during the late stages of the fever. To accommodate the need for more space for burials, Clarkson and the volunteer committee agreed to designate the nearby northwest public square—what is now Logan Square—for use as a burial ground.

Gerard's Heroism, illustration by G. F. and E. B. Bensell in Great Fortunes, and How They Were Made, by John D. McCabe, courtesy Project Gutenberg

Many in Philadelphia lionized Stephen Girard for agreeing to oversee the yellow fever hospital at Bush Hill. In this 1793 engraving titled “Gerard’s Heroism,” an artist depicted the merchant carrying a gaunt fever out of their home to an awaiting stagecoach.

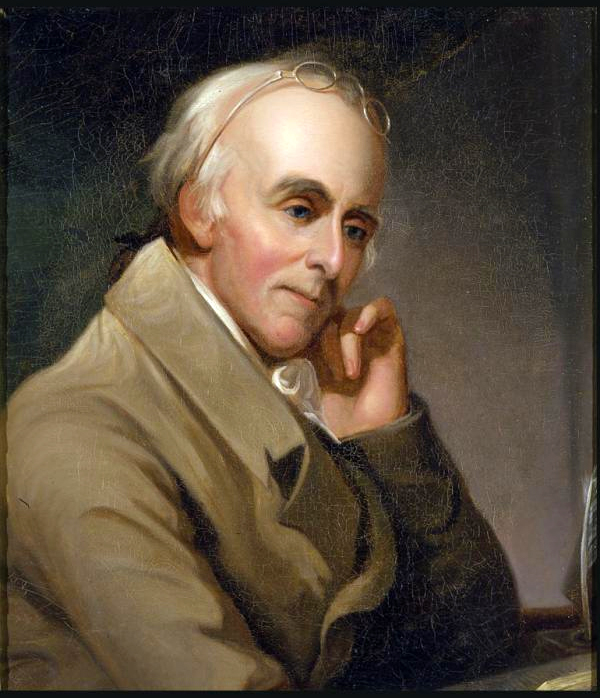

Benjamin Rush, portrait by Charles Wilson Peale, courtesy Independence National Historic Park

During the epidemic, Benjamin Rush’s controversial insistence on copious bloodletting and purges when treating yellow fever patients led to many disagreements with his fellow medical professionals. After the epidemic ended, Rush resigned from the College of Physicians in response to the criticisms of other doctors.

Doctors working elsewhere in the city disagreed with one another about the proper course of treatment. No doctor attracted more public attention and criticism than Benjamin Rush. Convinced that the fever caused inflammations of blood within the body, Rush sought to weaken inflammation by prescribing copious bloodletting and the mercury compound calomel to induce diarrhea and vomiting. Rush worked tirelessly during the epidemic, administering to around one hundred patients a day and catching the fever himself. A majority of doctors in Philadelphia rejected Rush’s approach, however, opting for treatments that combined induced sweating, soothing medicines, and mild purgatives. Rush obstinately defended his practices, even as his results belied his confidence. Though he maintained that he cured four out of five patients, more and more of his patients succumbed to yellow fever. Three of his own apprentices also died from the fever despite his bleeding and purges. Fueled by a zeal for his new cure and words of praise and encouragement he received from the public, Rush lashed out at his critics. In print, he condemned his detractors who fled the city while doctors like himself remained to serve. Once the epidemic ended, Rush resigned from the College of Physicians to protest many of the physicians who denounced his cure.

Benjamin Rush also encouraged leaders in Philadelphia’s free Black community to help combat the fever. Though an antislavery advocate, Rush believed that Black Americans possessed a natural immunity to yellow fever. In reality, immunity to yellow fever was gained by experiencing yellow fever earlier in life, which was a common occurrence for many free and enslaved Blacks brought from Africa or the Caribbean. The concept that Black Philadelphians possessed natural immunity dovetailed with the misguided belief that innate biological differences separated white and Black Americans. Rush asked for the help of Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, two leaders of the Free African Society, suggesting to them that yellow fever "passes by persons of your color." Black men and women acted as nurses for doctors, transported the sick from the city to Bush Hill, and buried corpses at the city’s Potter’s Field, present-day Washington Square. Within two weeks, Black volunteers began succumbing to the disease as well. Even with innate Black immunity proven wrong, Rush still adhered to the racist belief and wrongly insisted after the epidemic that Blacks suffered less since "the disease was lighter in them."

Absalom Jones by Raphaelle Peale, courtesy Delaware Art Museum

One of the leaders of Philadelphia’s Free African Society and founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Absalom Jones answered Benjamin Rush’s call for Black volunteers to combat yellow fever. Jones and other leaders such as Richard Allen organized hundreds of Black volunteers who nursed the sick, transported victims to hospitals, and buried the dead.

Instead of being rewarded and celebrated for their efforts and sacrifices, Black Philadelphians were shunned out of fear of infection and accused of profiteering. In a pamphlet published after the epidemic abated, Irish-born publisher Mathew Carey claimed that "the great demand for nurses afforded an opportunity for imposition, which was eagerly seized by some of the vilest of the blacks." Even as he acknowledged that leaders such as Absalom Jones and Richard Allen deserved "public gratitude," he repeated rumors that Black volunteers "were even detected in plundering the houses of the sick." Jones and Allen responded with their own pamphlet championing the services offered by Black Philadelphians. Jones and Allen also witnessed whites demand exorbitant prices and take the valuables of the deceased. One person threatened to shoot them if they tried to carry any bodies near his home. Meanwhile, many Black nurses worked for no pay, with one elderly nurse asking only for a meal for her services. Living in a city that still saw Blacks as inferior to whites, Jones and Allen needed to show their detractors that Black volunteers exhibited "more humanity, more sensibility" than white Philadelphians during the epidemic.

Beyond Philadelphia, exaggerated reports of the yellow fever epidemic convinced many towns, cities, and states to bar refugees and travelers suspected of carrying the disease. In New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, and beyond, stagecoaches and ferries from Philadelphia were prohibited from entering communities. Legislatures in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, North Carolina, and South Carolina passed laws quarantining vessels originating in Philadelphia. Philadelphia’s economy collapsed. Goods meant for export rotted in warehouses. Prices rose in a city where it was increasingly difficult to acquire paper money. Philadelphia received donations of money and goods from locales as close as Germantown and as far away as Boston, but these efforts did little to curb the city’s economic decline.

Colder weather returned to Philadelphia in late October, bringing frosts that froze the pools and cisterns Aedes aegypti needed to breed. As yellow fever deaths declined into November, President George Washington and Governor Thomas Mifflin returned to Philadelphia and reconvened the federal and state governments. The state government and College of Physicians established a permanent health office for the city along with more stringent sanitary guidelines, though the state and city governments still relied on volunteers to enforce these rules. In 1799, the city hired architect Benjamin Latrobe to design a new water system that would supply Philadelphians with clean water for drinking and sanitation. Still, Philadelphians largely failed at combating yellow fever, which returned to the city eight different times over the next two decades. Only after Cuban epidemiologist Carlos Finlay and U.S. Army doctor Walter Reed proved in the final decades of the nineteenth-century that mosquitos transmitted yellow fever could medical and civic leaders begin to effectively prevent yellow fever epidemics.

Philadelphia’s place as the political, commercial, and cultural capital of the young United States allowed the city’s economy to recover shortly after the winter frosts arrived. Still, yellow fever outbreaks occurred again in 1794, 1796, 1797, and 1798, each time bringing economic decline that contributed to Philadelphia ceding its status as the nation’s financial capital to New York City. Incapable of stopping recurring outbreaks, politicians, reformers, and intellectuals blamed yellow fever and other disease outbreaks on the dense cities they so often harmed. They compared contaminated cities with the healthier rural country. While some leaders insisted cities be designed to include more green spaces, others championed moving away from cities and onto western lands taken from Native Americans. The yellow fever epidemic of 1793 was the first and deadliest outbreak in a series of yellow fever epidemics that forced Americans in and outside of Philadelphia to rethink how United States citizens responded to the disease.

Sources:

- A.B. or Anonymous. “As the late rain….” Dunlap's American Daily Advertiser, no. 4554, 29 Aug. 1793, p. 3. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex. Accessed 24 July 2022.

- Carey, Mathew. A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia: with a Statement of the Proceedings that Took Place on the Subject in Different Parts of the United States. Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1793. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections, https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-8710344-bk.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Yellow Fever.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/index.html. Accessed 24 July 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Yellow Fever: Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Treatment.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/symptoms/index.html. Accessed 24 July 2022.

- Currie, William. A Description of the Malignant, Infectious Fever Prevailing at Present in Philadelphia; with an Account of the Means to Prevent Infection, and the Remedies and Method of Treatment, Which Have Been Found Most Successful. Philadelphia: T. Dobson, 1793. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections, https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-2548023R-bk.

- Finger, Simon. The Contagious City: The Politics of Public Health in Early Philadelphia. Cornell University Press, 2012.

- Fried, Stephen. Rush: Revolution, Madness, and the Visionary Doctor Who Became a Founding Father. Crown, 2018.

- Gum, Samuel A. " Philadelphia Under Siege: The Yellow Fever of 1793." Literary and Cultural Heritage Maps of Pennsylvania. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University, Summer 2010. Superseded Spring 2022. https://web.archive.org/web/20220804001159/https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/feature-articles/philadelphia-under-siege-yellow-fever-1793. Accessed 3 Aug. 2022.

- Hogarth, Rana Asali. “The Myth of Innate Racial Differences between White and Black Peoples’ Bodies: Lessons from the 1793 Yellow Fever Epidemic in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 9, no.10, 2019, pp.1339-1341. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6727282/pdf/AJPH.2019.305245.pdf.

- Jones, Absalom and Richard Allen. A Narrative of the Proceedings of Black People, during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793: and a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown upon Them in Some Late Publications. Philadelphia: William H. Woodward, 1794. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/02013737/.

- McCoy, Charles Allan. Diseased States: Epidemic Control in Britain and the United States. University of Massachusetts Press, 2020.

- McNeill, J.R. Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Nash, Gary B. Forging Freedom: The Formation of Philadelphia’s Black Community, 1720-1840. Harvard University Press, 1988.

- Newman, Simon P. Embodied History: The Lives of the Poor in Early Philadelphia. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

- Palmieri, Brooke Sylvia. “American Philosophical Society.” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, 2016, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/american-philosophical-society.

- Powell, J.H. Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793. Martino Publishing, 2016.

- Smith, Billy G. The “Lower Sort”: Philadelphia’s Laboring People, 1750-1800. Cornell University Press, 1990.

- Smith, Billy G. Ship of Death: A Voyage That Changed the Atlantic World. Yale University Press, 2013.

- Weld, Isaac. Travels Through the States of North America and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada During the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797. London: John Stockdale, 1799. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/17013770/.

Plan of the City of Philadelphia, map by John Hills, courtesy Library of Congress