Half a century ago, watches all had analog displays; they used mechanical hands in order to display the time. This antiquated form of display persisted even after the development of electric watches powered not by mainsprings but by batteries. A watch that used numerical digits to display time would not exist without the ingenuity of a Pennsylvania company.

The concept of a digital display element was introduced to the public in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Director Stanley Kubrick had asked the Hamilton Watch Company of Lancaster to create the futuristic digital clock for his film. The oval clock with glowing red digits and the prominent Hamilton logo captured the public’s attention. The public didn’t have long to wait until the digital clock was transformed into watch form. According to the then head of Hamilton’s digital watch division, John Bergey, the digital clock created for the film inspired the creation of a watch with a similar display. Already known for producing the first electric watch, the Hamilton Watch Company was the ideal birthplace for the first digital watch. The first prototype “Wrist Computer” was unveiled on the Tonight Show by Johnny Carson on May 5, 1970. When hearing the $1500 price tag for the production model, Carson quipped: “The watch will tell you the exact moment you went bankrupt!”

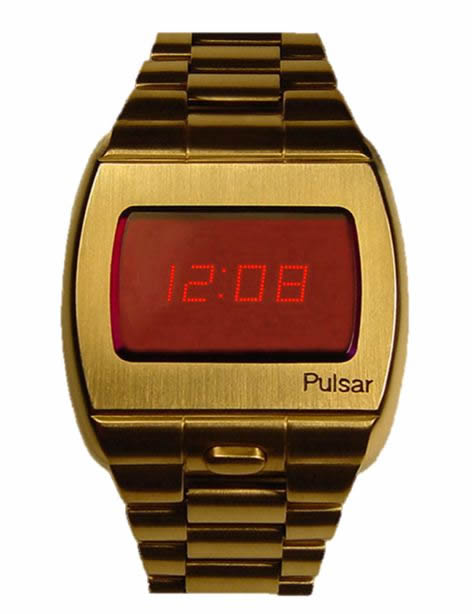

The Pulsar was the first watch to display time in a digital format, using light emitting diodes (LEDs), as well as the first all-electronic watch with no moving parts. Featuring 44 integrated circuit (IC) chips and 4000 bonding wires, the watch made full use of the recent innovations in IC and LED technology. Its use of the more mature LED technology let it beat out competitors using liquid crystal display (LCD) technology, such as the BWC/Optel DSM LCD released in 1973.

The honor of being the world’s first digital watch is great considering that it was the first new way to tell time in half a millennium. Watch experts, such as Henry Fried, consider the digital display the greatest technological leap since the hairspring in 1675. The New York Times called it a space-age “wrist computer” and announced it was “a new era in the science of measuring time.” Richard J. Blakinger, the Hamilton president, described the development of the watch as “a dramatic breakthrough in the science of horology which signals the opening of a totally new approach to the design and manufacture of portable timepieces. Since this advanced product is a fixed program computer, it is conceivable that other programs are possible and that some day in the future there will be a programmable wrist computer which would respond to a variety of useful programs personally selected by the wearer.” Marketed as a “time computer,” the Hamilton company would later create a subsidiary called Time Computer, Inc. just to manufacture and market the Pulsar.

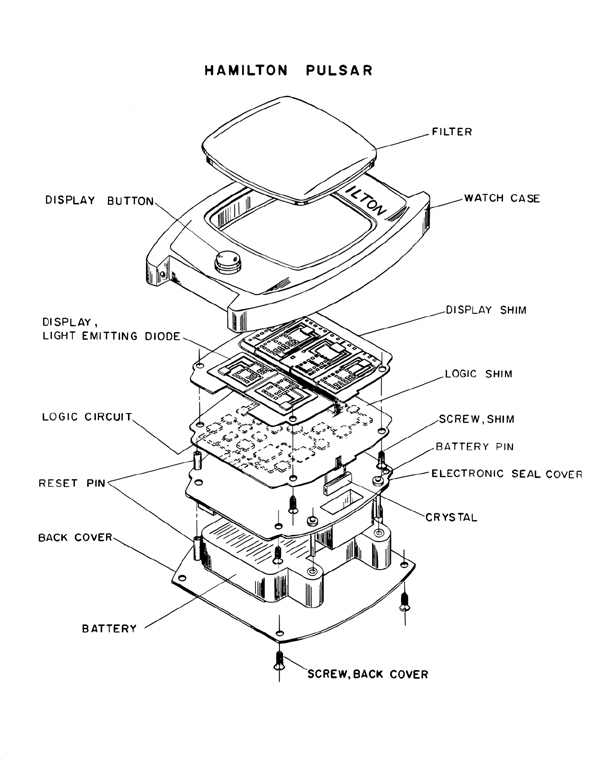

The prototype Pulsar consists of three major components: a time module with display circuits, a quartz crystal, and a rechargeable battery. The components were developed by the Hamilton Watch Company with Electro/Data, Inc. Electro/Data had made early progress with developing miniaturized time displays in 1968 and entered into a contract with the Hamilton Company on December 1, 1969 to jointly develop a digital watch. The initial time module had 44 ICs built using TTL technology, equivalent to 3474 transistors. It consisted of seven ceramic circuit boards, each with its own function. The time-keeping signal was supplied by a quartz crystal vibrating at 32768 Hertz, about three times the frequency of crystals being used in electric analog watches. The high frequency crystal ensured that the time deviated by no more than three seconds a month, making it the most accurate watch in the world. The entire watch was powered by a three-cell, 4.5-volt, rechargeable NiCad battery. Under normal use, the battery lasted about six months. The watch was to come with a replacement battery and charger.

The LED display for the watch consisted of 27 diodes per digit and was modeled on the Hewlett-Packard 5082-7000, the first LED display package. The red digits were created by passing a current through aluminum gallium arsenide (AlGaAs). The use of LEDs gives the digits a very distinct, bright glow. Photosensors monitored the ambient light to decrease the brightness in the dark. The display consumed a lot of power compared to LCDs. When the initial prototype was first demonstrated, the battery only lasted for 20 minutes. The Hamilton employees had to discreetly switch between different prototypes as the batteries were replaced. Pressing the button turned on the display for 1.25 seconds. The rest of the time, the display is off to conserve energy.

The first production model was released on April 4, 1972; a special Hamilton Pulsar digital watch had an 18-carat gold case and sold for $2100. To put this into perspective, a top of the line Rolex was $150 cheaper! The development of low-current CMOS technology allowed for the advanced 25-IC module used in the production watch. The 27-dot display was reduced to a seven-segment type. Two slots on the side of the case provided access for a magnet stored in the clasp used to set the hour and minute. The first models showed the time only, no date was displayed.

The name “Pulsar” was chosen to imply space-age technology, derived the name of the recently discovered pulsars. Legend says that Bergey came upon the term while reading an astrology magazine, in which the pulsar was described as “pulsating light emitting from a star with unprecedented accuracy”. This was an apt name for the Hamilton’s new “shining” masterpiece.

The Pulsar is America’s biggest watch success story. The initial 400 limited edition gold watches were sold by the end of the first year, despite its high price. The thriftier steel model at $275 also sold very well. At the height of the watch’s popularity, the company was selling ten thousand units per month, outselling every high-end watch in the world. It was also the first watch imported into Switzerland, the famous watch-making country. Bergey recalls visiting Tiffany’s New York store to see the success of the watch he had created. “The Pulsar showcase was a hub of activity,” he recounts. “Costumers would sidle up to the counter, pluck down a wad of money and point to the Pulsar of their choice as casually as if they were buying a jelly doughnut.”

In addition to the high watches at Tiffany’s, Pulsar produced an even more expensive and equally innovative watch: the world’s first calculator watch. It was offered for sale just for Christmas 1975. The first version of this watch was produced in an 18k gold Limited Edition for a whopping $3950. This was, as Pulsar historian Dennis Klein writes, “the most expensive production Pulsar.” The various versions of this watch, including the much cheaper ones, proved to be the most profitable models Pulsar had. Like the first LED in 1970, the calculator watch was unveiled with on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. The comedian quipped about the cost (“If you have that much money you don’t have to be on time anywhere!”) and about how it worked (“Actually the secret to this is there’s a tiny Japanese accountant in here.”).

The watch had many famous admirers: U.S. President Gerald Ford as well as Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, the Shah of Iran, and numerous celebrities, including actor Roger Moore and comedian Jerry Lewis, all owned the Pulsar. James Bond was even seen wearing the Pulsar in replacement of the Rolex or Omega watches he typically wears; in the Bond film Live and Let Die, Roger Moore wears a steel Pulsar and evens depresses the display button to check the time. The Pulsar was a truly monumental watch; Time Magazine included the watch in its list of the top twenty watches of the 20th century and, in 2005, PCWorld ranked it as the 22nd greatest gadget of the past 50 years. Additionally, the Smithsonian Institution exhibits the watch as an important contributor to the technology of quartz watches.

The Pulsar enjoyed only a few years of success until Texas Instruments started mass producing LED watches in 1975. These watches retailed for only $20, reduced to $10 in 1976.

Pulsar started out with great fanfare in Lancaster; its end, however was both quiet and confusing. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Hamilton Watch Company diversified its holdings. In fact, the watch making that had started the entire company became a mere subsidiary for a larger company. As Don Sauers wrote in Time for America “the Parent became the Child.” The “electronic watch project,” as the Pulsar started out, was a separate division of the larger firm and unconnected with the Watch Division. After various corporate moves that included rebranding and divestiture of the digital watch facilities to Time Computer, Inc. and to Rhapsody, Inc. of Philadelphia, the Pulsar would go out of production by 1978. Rhapsody would sell the Pulsar trademark to the Seiko company in 1984; Time Computer’s trademark is owned by Pulsar historian Dennis L. Klein.

Though Hamilton’s Pulsar line of watches only lasted a few years, it has had a lasting effect on society and how we tell time. It started the revolution of digital watches. They say that “the flame that burns twice as bright burns half as long.” In Hamilton’s case, the Pulsar had the brightest flame of all watches.

The Center wishes to thank Dennis L. Klein of Oldpulsars.com for his knowledge about the Pulsar and his assistance in illustrating this article.

Sources:

- Bergey, John M. and Richard S. Walton. Solid State Watch. U.S.: Patent 3672155. June 1972.

- Computer History Museum. “1974 - Digital Watch is First System-On-Chip Integrated Circuit.” 14 Oct. 2010. Computer History Museum - The Silicon Engine. Web. 15 Oct. 2010 <http://www.computerhistory.org/semiconductor/timeline/1974-digital-watch....

- Dargent, Bruno M. Integrated Circuit Solid State Watch. U.S.: Patent 3760584. September 1973.

- Fisher, Arthur. “Look, Little Old Swiss Watchmaker-No Hands!” Popular Science July 1970: 51.

- Forrer, M. P. “Survey of Circuity for the Wristwatches.” Proceedings of the IEEE Sep. 1972: 1047-54.

- Klein, Dennis L. “Electro Data.” Oldpulsars.com. 2010. 25 May 2011 <http://oldpulsars.com/Hamilton-TCI.htm>.

- Klein, Dennis L. Personal Communication with Alan Jalowitz. 22 Feb. 2011.

- Lutenegger, Donald J. Wristwatch. U.S.: Patent D229085. Nov. 1973.

- Pulsar LED Watches. 13 Mar. 2010. Web. 10 Oct. 2010 <http://www.oldpulsars.com/>.

- Rostky, George. “In the ‘70s, time was of the essence.” 9 April 2004. EE Times. Web. 14 Oct. 2010

- Sauers, Don. Time for America. Lititz, PA: Sutter House, 1992.

- Smithsonian Institution. “John Bergey.” 16 Oct. 2007. The Quartz Watch. Web. 13 Oct. 2010 <http://invention.smithsonian.org/centerpieces/quartz/inventors/bergey.html>.

- —. “Pulsar.” 16 October 2007. The Quartz Watch. Web. 10 Oct. 2010 <http://invention.smithsonian.org/centerpieces/quartz/coolwatches/pulsar.....

- Stephens, Carlene and Maggie Dennis. “Engineering Time: Inventing the electronic wristwatch.” The British Journal for the History of Science December 2000: 477-497.

- Trueb, Lucien F. “The Hamilton Pulsar: A Space Odyssey.” WatchTime April 2004: 134-138.

- Volk, Andrew M, Peter A Stoll and Paul Metrovich. “Recollections of Early Chip Development at Intel.” Intel Technology Journal (2001). Web.

- Walton, Richard S. Electronically Controlled Timepiece Using Low Power MOS Transistor Circuitry. U.S.: Patent 3560998. February 1971.

- Weaver, J. D. Electronic Clocks and Watches. London: Newnes Technical Books, 1982.