THE OBJECT of this association is to promote the cultivation of the FINE ARTS in the United States of America, by introducing correct and elegant copies from works of the first masters in sculpture and painting and by thus facilitating the access to such standards, and also by occasionally conferring moderate but honorable premiums and otherwise assisting the studies and exciting the efforts of the artist gradually to unfold, enlighten and invigorate the talents of our countrymen.

Application for Charter

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

December 26, 1805

Since its conception in 1805, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) has stood as a “guardian of the arts in America,” training many of the country’s premiere artists and procuring an important collection of American masterpieces supporting each movement in American art from the Victorian to the avant-garde. However, the Pennsylvania Academy’s ongoing legacy is only partly due to its museum. Since its conception, the school has defined the country’s art curriculum and has pushed social boundaries to broaden the nation’s artistic development. Over the past two centuries, the Academy has grown into an internationally recognized institution focused on the preservation of historical American pieces, the procurement of contemporary American works, and the training of future artists, both domestically and internationally.

The Early Years (1805-1876)

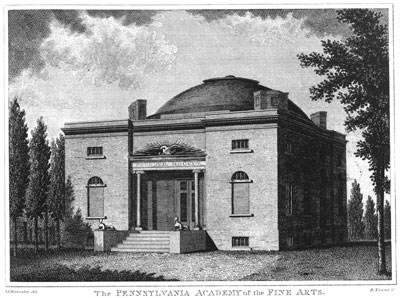

In an attempt to stimulate the arts in the new nation, Charles Willson Peale founded the Columbianum in 1794. However, failing the next year after its first exhibition, the organized art scene in Philadelphia waned until 1805, when C.W. Peale, Rembrandt Peale, and William Rush, among a group of 71 business and legal men founded the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts on December 26, signing the charter in Independence Hall. On January 3, 1806, George Clymer, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, was chosen President for the infant institution along with a board of 12 individuals. In April of 1807, John Dorsey’s building, located on Chestnut Street between 10th and 11th Street, opened to exhibit PAFA’s collection of casts of ancient sculpture recently purchased in Paris. By May, visitors were viewing an exhibition of European paintings and casts within its halls. Mondays were reserved for women and all of the plaster casts of nudes were removed from its walls as they were viewed as indecent for female visitors.

Following the establishment of the institution as a predominant national leader in the arts, C.W. Peale pushed his plans to expand the museum to include a school for the education of American artists. In 1810, the Academy opened its doors to students, offering a fairly typical American art education, largely focusing on charcoal drawings of plaster casts, but by 1812, the board established a Life Academy which introduced human models to the curriculum. The next year, Joseph Allen Smith provided students with a substantial increase in material from which to study, sending a generous collection of paintings to America. However, the cargo ship was intercepted by the British and after a court decree released the paintings, a global precedent favoring free trade of works of art was established.

While Peale’s attention in the 1810’s was focused on the establishment of the school, the board continued to expand its collection and promote the museum. However, having focused on a vast European collection, the Society of Artists of the United States protested the institution’s disconnect with contemporary, especially domestic, artists. In response, the Academy organized the first Annual Exhibition, a tradition which would continue from 1811 until 1969. To ensure a continuing friendship between the Academy and artists, a body of 24 Pennsylvania Academicians was given the duty of managing the Annual Exhibitions and the school until 1870.

Even through all of the tension in the early years, clear gains were made in terms of the Academy’s growing collection. Possibly of most importance were Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s gift of 24 books of engravings by Piranesi and William Binham’s donation of Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait of George Washington. A few years later, in 1816, PAFA became a recognized art collector through its purchase of Washington Allston’s The Dead Man Restored to Life by Touching the Bones of the Prophet Elisha for $3500, and then, Benjamin West’s Death on a Pale Horse for $7,000 in 1820, both of which required mortgaging the institute’s building. Both masterpieces were by American painters.

After Clymer’s death in 1813, Joseph Hopkinson took the presidency, leading PAFA into an age of spender. Even though his presidency was filled with its fair share of pecuniary concerns and disputes between artists and board members, under his guidance, the institute more than doubled its floor space. Filling the new gallery space with masterful works, Hopkinson’s additions brought a substantial increase in sustainability, leaving the institute in particularly good financial shape upon his death in 1842. Unfortunately just a few years after, the main building was burned by a “deranged incendiary” which destroyed the cast collection and several important European paintings.

As the Academy struggled to recover following the fire of 1845, the institution’s expanding influence became apparent. Honorary Professional Member of the Academy, Asher B. Durand expressed his “full appreciation of connection with the oldest Institution of its kind in the country, and which has been so long prominent for the service it has rendered to the great cause of art.” Not only had the Academy received national recognition, but its efforts were also noted internationally. President Henry Gilpin recounted upon his return from Europe in 1854, “I assure you, it has been a source of constant gratification to me to find that my connection with the Academy is a passport to the good feeling and attention everywhere of artists and friends of artists.” While away, Gilpin spoke to German explorer Baron von Humboldt who held that PAFA is “an honourable pioneer in one of the many roads of usefulness that are considered as characteristic of the American spirit.”

However, much of the Academy’s fame, at least in the early years, was derived from its expensive European painting collection. This comes as no surprise as American painting had yet to flourish and many of the board members were businessmen seeking sound financial investments. American painter and director of the Academy, James R. Lambdin, attempted to sway the board’s preference by proposing that the yearly prizes must go to paintings “by an American artist and executed within the United States or by American artists residing temporally abroad.” While his words went largely unheard, W. J. Stillman and J. Durand’s publication, The Crayon, reported on the issue,

The Pennsylvania Academy is noble preserving in the purchase of works of Art....Three pictures were procured last year: a landscape by Weber, The Dying Brigand, by May, and Datheen Preaching in the Neighborhood of Ghent, by Wittkamp; the first two were appropriate additions to the Academy’s collection, and, under the circumstance, so was the picture by Wittkamp. The latter acquisition however, is a bad precedent, if likely to be followed by similar successors. We presume the Academy desirous of favoring the growth of Art in America...let it judiciously buy, therefore, all works by native artists who need the encouragement and appreciation of home patronage, particularly that of an institution; they have a right to in through their genius without regard to any national considerations whatever.

The Academy continued predominately purchasing European pieces through the 1870’s, but its focus shifted, largely because of Edward L. Carey’s collection of modern American paintings donated in 1879. This change in attitude also redirected the nature of the Academy. According to director Frank H. Goodyear Jr., “Traditionally, academies have taken a stern view toward contemporary art. Through the latter part of the nineteenth century the Pennsylvania Academy stood in the vanguard of artistic taste….Even in the school, where one might expect a more conservative bent, the instruction was innovative.” Coming with the American focus and encouragement of innovation, the Academy flourished. Gilpin reported that the number of stockholders had risen from 304 in 1845 to 813 in 1858. Not only had support amongst investors increased, but attendance also soared from an average of 5,000 visitors per year in the 1840’s to 13,000 in the 1850’s.

An Established Institution (1876-1905)

The Pennsylvania Academy’s newfound financial stability and support permitted it to address its impending need to expand. In 1870, the Chestnut street building was sold to appropriate funds for a new home. Its replacement, the Furness-Hewitt building opened in 1876 and, with it, the reopening of the school which was left without classrooms for the period of construction. Its revitalization brought great pride to PAFA with its directors exclaiming that the school had “no superior in any country.” Up to this point tuition to the school had been free, but with the new building and distinguished faulty including the European trained Thomas Eakins, Joseph Bailly, and Dr. W. W. Keen, along with a more orchestrated curriculum, the school began to notice “the rapidly decreasing available funds of the Institution” which prompted a modest tuition of less than $10.

Following Thomas Eakins’ vision, the school became the forerunner in a new movement in arts education in America. Drawing from the example of distinguished European ateliers, Eakins refocused his students’ study on the human figure. Since the school’s conception, the human body had been a popular topic of lectures and studies, but the students learned primarily from anatomical drawings and casts. Eakins felt that this methodology was inadequate, asserting, “To draw the human figure, it is necessary to know as much as possible about it, about its structure and its movements, its bones and muscles, how they are made, and how they act.” Just as artists had done since the Renaissance in Europe, Eakins brought his students to the source, providing access to human and animal cadaver dissections which became a staple of the anatomy classes offered at the Academy in the 1870’s and 1880’s.

Not only did Eakins bring both male and female students into the dissections (although segregated), but he also provided female students with access to male models wearing only a loincloth. With the public already in shock over his liberal actions, Eakins met with Amelia Van Buren to discuss some difficulties she was having with her figures. He is reported to have taken her into his office where stripped in front of her and demonstrated how the pelvis worked and “gave her the explanation as I could not have done by words only.” While women had been admitted to the school since 1844 when the board of directors gave women “exclusive use of the statue gallery for professional purposes”, they were first permitted into anatomy and cast drawing courses in 1860 and were given access to nude female models in 1868. Surprisingly, the Academy’s treatment of women actually exceeded that of the more liberal instructions in Europe. But Eakins’s final progressive action would land the Academy in the forefront of radical arts education and in its largest controversy. The removal of the loincloth from the male models in the female studios, escaladed his controversial views beyond society’s limits forcing Eakins to resign in 1886.

In addition to his emphasis on the human figure, Eakins accelerated his student’s education by incorporating painting into the curriculum at an early stage. This emphasis, according to Eakins was superior to focusing on the charcoal based approach at other institutions, such as the National Academy, because “the brush is a more powerful and rapid tool than the point or stump…the main thing that the brush secures is the instant grasp of the grand construction of a figure. There are no lines in nature…;there are only form and color.” When art critic William C. Brownell visited the school and observed the students, he noticed that students, “almost without exception…use the brush--which would excite wonder and perhaps reprehension from the pupils of the National Academy.” A half decade after his visit, the use of the brush had become standard in major art academies across the country.

As the Pennsylvania Academy’s innovative curriculum circulated the globe, becoming the standard in liberal fine arts education, the Academy’s students began to reach out into the international world as well. In 1891, John R. Connor was given the first scholarship to study abroad. Due to tight expenses, few students were given such scholarships through the 1890’s, but in 1902, Emlen and Priscilla Cresson provided an endowment for foreign studies which still supports traveling students in the new millennium.

A New Center for the Arts in America

(1905-present)

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts continued to grow through its centennial celebration in 1905. By 1908, the museum received 214,594 guests. While its curriculum was radical for an academy and it continued to purchase works by prominent students, faculty, and other living American artists, the Academy’s foundation was still engrained in the traditional European technique. In addition to its classical teachings, the institution’s leadership maintained a conservative approach; President Edward T. Lewis focused much of the school’s resources on traditional, historical portraiture, but colleague John Trask balanced the purchases with modern American pieces. Nonetheless, the Academy’s Annual exhibitions were still predominantly traditional, but its exhibitions were beginning to introduce modern styles to the public. The first avant-garde exhibition showcased a series of photographs from the Photo-Secession gallery in New York. With the expansion into the avant-garde in the classroom, President Lewis remarked in 1914 that the school was in a “more flourishing condition” than at any previous time.

However, the Academy’s influence would begin to diminish in the 1930’s due to a combination of internal and external political and artistic forces. After the death of Lewis in 1932, the Academy fell into financial difficulty from its board’s “limited aspirations” and its conservative views of art. Additionally, with the opening of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and Museum of Modern art, artists began to shift their attention away from the historically recognized Academy to the more liberal institutions.

Over the next four decades, the Academy struggled to produce any significant contributions to the art scene in America. When Joseph Fraser began his 35 year term as director in 1936, the Academy had become “a slumbering giant,” still important due to its expansive collection, but relatively inactive in contemporary artistic concerns. In order to demonstrate its continuing emphasis on the arts, the board of directors established a conservation department in 1970 to repair many of the pieces which had been neglected over the years. Two years later in 1972, almost a hundred years after its construction, the board began restoration of the Furness-Hewitt building in an attempt to reestablish the Pennsylvania Academy as one of the premiere institutes in the world.

Since the turn of the century, PAFA has again entered a stage of expansion. To usher in the new millennium, the school purchased the Federal building with the support of Dorrance H. Hamilton. Then during its bicentennial, in 2005, the renovations were completed and the Samuel M.V. Hamilton building was opened providing its students with state-of-the-art studios to push their studies into the future, and the Academy was honored by being the first art institution to receive the National Medal for the Arts. In a gesture to its progressive past and its new role in a much larger arts scene in Philadelphia, PAFA and the Philadelphia Museum of Art jointly purchased Thomas Eakins’ The Gross Clinic in 2007. Then, continuing on Eakins’s more substantial curriculum, the school began offering its own Bachelor of Fine Arts degree, independent from the University of Pennsylvania, in 2008.

Over the past two centuries, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts has continued to develop as an international power in the fine arts community. Beginning with its foundations in the infant nation, the Academy molded the arts to establish a national identity. Starting as a typical art school, PAFA quickly became the most progressive force in the art world, rising to challenge the established ateliers of Europe. After initiating several radical curriculum changes, the Academy’s program diffused throughout the United States and around the world to provide the basis for the modern, traditional art education. Since its conception, PAFA has not only become one of the great American art schools, but has also established itself as a global authority on American art history, holding and conserving one of the most important collections. Combining the institute’s prominence in both public education and artist training, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts has been, and continues to be, the “guardian of the arts in America.”

Sources:

- Barber, Alice. Female Life Class. 1879. The Philadelphia Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA. Ancestral Pioneers: Women Who Set the Course. 12 Nov. 2009. <http://www.percontra.net/barber%20stephens.jpg>.

- Corliss, George. “Art Collection.” Letter to Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America. 19 Dec. 1884. MS. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA.

- Crane, Tom. The Samuel M. V. Hamilton Building. Photograph. The Samuel M. V. Hamilton Building. 12 Nov. 2009. <http://www.pafa.org/SiteData/images/P64_SMVH_revised/58e79f5bc3f3eaeafd4....

- Eakins, Thomas. Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic). 1875. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA. Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic). 12 Nov. 2009. <http://www.pafa.org/SiteData/images/EAKINS_2007_2-L/d41d8cd98f00b204e980....

- FAF:PFPAFP Form and Function: Proposals for Public Art for Philadelphia. Philadelphia: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1982.

- Fellowship of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts the unbroken line, 1897-1997 : 100 years of Fellowship : a centennial exhibition, September 19-November 30, 1997. Philadelphia: The Fellowship, 1997.

- Goodyear, Frank H., Jr. “A History of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1805-1976.” Traditional Fine Arts Organization. 28 Oct. 2009 <http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/8aa/8aa131.htm>.

- Gutekunst, Frederick. The Historic Landmark Building. 1876. Photograph. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA. The Historic Landmark Building. 17 Nov. 2009. <http://www.pafa.org/Museum/Research-Archives/The-Buildings/Landmark-Buil....

- Pepper, George S., and George Corliss. “Portrait of General George H. Thomas.” Letter to Senate and House of Representatives of the United States. 13 Jan. 1885. MS. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA.

- Rutledge, Anna W., comp. Cumulative Record of Exhibition Catalogues The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts 1807-1870. Philadelphia, PA: The American Philosophical Society, 1955.

- The First Building of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. 1809. Photograph. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA. Early PAFA Buildings. By Benjamin Tanner. 12 Nov. 2009. <http://www.pafa.org/SiteData/images/P62_tanner_new/14a802e292c4177009290....

- The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In Private Hands: 200 Years of American Painting. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 2005.

- The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Annual Report. Rep. no. 144. Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1949.

- The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Annual Report. Rep. no. 162. Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1967.

- The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Annual Report. Rep. no. 175. Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1980.

- The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Annual Report. Rep. no. 192. Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1997.

- The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. “Annual Discourse.” Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. 1810. Address.

- The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. American sculpture in the Museum of American Art of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Philadelphia, PA: Museum of American Art of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1997.

- The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In this Academy. Washington DC: Museum, Inc, 1976.

- The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1805-2005 200 years of excellence. Philadelphia, Pa: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2005.

- The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The American paintings in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts an illustrated checklist. Philadelphia: The Academy, University of Washington, 1989.

- The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. 27 Oct. 2009. <http://www.pafa.org>.

- Werbel, Amy. Thomas Eakins Art, Medicine, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia. New York: Yale UP, 2007.

- West, Benjamin. Death on the Pale Horse. 1796. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA. Death on the Pale Horse. 12 Nov. 2009. <http://www.pafa.org/SiteData/images/collectionimages/large/West_1836.1_l....