On a cold day in wintery Philadelphia, Theophilus Van Kannel sat working his job at a building’s lobby desk. During the course of the day, several people entered and exited the building’s main doors. Each person who entered and exited exposed Van Kannel to a gust of frigid winter air. In describing his enemy, he said, “every person passing through [a door from the outside] first brings a chilling gust of wind with its snow, rain or dust, including the noise of the street; then comes the unwelcome bang!” With few options in front of him, Van Kannel put his mind to work, eventually patenting an alternative to the standard door shortly thereafter.

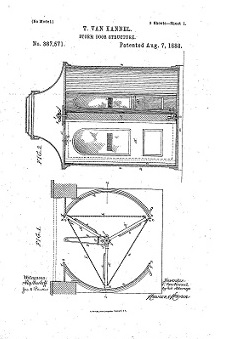

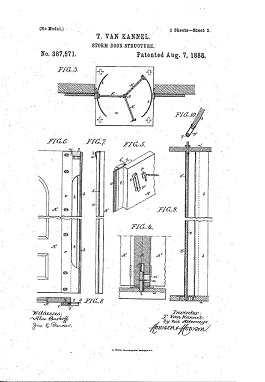

Van Kannel’s alternative came in 1888, with a design he referred to as the “New Revolving Storm Door.” The design spaced out four doors equally on a pivot, with two of the doors always making contact with the wall. As a result, there was little transfer of interior and exterior air, as well as limited amounts of noise and fumes entering the building. Several groups, such as the Franklin Institute’s Committee on Science and the Arts, considered the door to be an enclosed turnstile, with the benefit of controlling the transfer of both air and patrons. For Van Kannel, the design proved successful, as it addressed the flaws of the traditional door. On August 7, 1888, Van Kannel was awarded a patent on his design, beginning a prosperous career.

With his design finalized in 1888, Van Kannel’s revolving doors began springing up throughout the Philadelphia area. Stores, restaurants, and even large businesses turned to Van Kannel’s revolving doors for their buildings. In late 1888, J. T. Harker, manager of Thackray’s Restaurant in Philadelphia, praised the doors saying, “In the coldest days during the great blizzard, we felt no discomfort, as it completely excludes the strongest wind, even while persons are passing in or out.” Harker later added, “The absence of all slamming, and the exclusion of street noises, are also an important feature.” Perhaps the greatest compliment paid to Van Kannel at the time was being awarded the John Scott Legacy Medal for useful inventions by the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. Given all the positive feedback, the demand for revolving doors increased.

To keep up with the demand, Van Kannel started the Storm-Proof Door Company of Philadelphia. Businesses around the city wanted this new, more efficient design. Soon enough, word spread to neighboring communities and eventually reached New York City. One of the first businesses in the city to make use of Van Kannel’s design was Rector’s Lobster Palace, a restaurant in Times Square. When the business first installed the door, many simply walked in to take a spin around the door and leave. The door was noted by others for its efficiency, and ultimately was adopted in numerous buildings citywide.

Building owners, specifically skyscraper owners, found Van Kannel’s revolving doors more beneficial for numerous reasons. Certainly, Van Kannel’s original intentions of reducing wind gusts and outside noises were important, but other benefits were also considered. The impact of the doors on air pressure was a critical factor. Architects had found that the stairways and elevator shafts located in the lobby created a vacuum in the building, making traditional doors much more difficult to open and keep closed. Van Kannel’s design helped eliminate this problem by preventing a direct opening between the interior and exterior of the building.

While the issue of a vacuum was crucial, perhaps the greatest reason to turn to Van Kannel’s door was for aesthetics. Businesses searched for an attractive and welcoming entrance to their buildings; Van Kannel’s door brought that to them. Some designs allowed a glass case at the center pivot point, allowing art or other items to be placed inside. Most notably, however, was the visual effect created by the doors. Architectural historian Andrew S. Dolkart said on one building: “When you walk from the small space in the revolving door and step into the lobby the space just seems to explode. The lobby feels so big compared to the small space in the door that you don’t even notice that the lobby isn’t as big as you thought it would be. That small space in the door is critical to creating the illusion.” This visual effect proved attractive to businesses, as many buildings across the city turned to Van Kannel’s design.

The impact of revolving doors turned out to be even larger than business use. With the introduction of film came comedic use of the revolving door. Several slapstick comedies used the door in some capacity, such as Charlie Chaplin’s 1917 film, The Cure. Many, like Chaplin in The Cure, would walk into the door and take several turns around, becoming dizzy and disoriented in the process. Others would walk through the door, only to get split up from others they were with, such as The Three Stooges. An even larger group of others would find their way into the door, without ever finding their way out. No matter its use, the revolving door proved a comedic hit amongst early audiences of slapstick.

Even artists turned to revolving doors for their work. In 1916, artist Man Ray turned to the idea for a Manhattan art exhibit. Ray created collages on each door component of the whole revolving door fixture. Spectators were able to spin the door around, seeing each of the unique collages he had created. Appropriately, Ray titled his newest piece Revolving Doors.

While it was present in film and art, revolving doors even worked their way into everyday language. Popularized shortly after World War II, the phrase “revolving door” has come to refer to recurring events in various aspects of life. Most often, the term is used in political environments, but can be found wherever a metaphor for a circular idea is needed. One of the earliest can be found in 1914 in The Atlanta Journal Constitution. The newspaper read, “Felix Diaz is our idea of a man who wants somebody else to push the revolving door of revolution around for him.”

With the revolving door exploding in both architecture and entertainment, Van Kannel pushed his door into a new venue: the home. Through business brochures and discussions, Van Kannel insisted that his revolving door could possibly be “an ideal entrance enclosure for residences.” Although many people were amused and in awe of Van Kannel’s innovative design, few wanted to dedicate the money and time to installing a revolving door in their home.

As the demand for Van Kannel’s doors continued in public buildings, new production means were sought. By the turn of the century, clients requested that cheaper materials be used instead of wood—the most logical choice was steel. At the age of 66 and with no children, Van Kannel sold his revolving door company, by then known as the Van Kannel Revolving Door Company, to International Steel in 1907. This transition to steel began a long line of innovations to the revolving door which are still in place today.

Today, revolving doors play an important role in business design. Although architects rely on the original practical uses of Van Kannel’s design, technology has found even more benefits. While Van Kannel’s design was energy efficient in terms of cooling and heating costs, it has also been found beneficial in generating energy. By capturing the energy generated by the revolution of the doors, several buildings now utilize that energy to power certain building elements—the first being Natuurcafé La Port in the Netherlands in 2008. Additionally, by creating doors that are collapsible, revolving doors prove to be a much more efficient way for large groups of people to exit a building in the event of a fire.

Given that skyscrapers are often targets for criminal activity, security elements were added to the revolving door. While the original design provided a way to control the number of people entering a building at a given time, it has also proved itself crucial in monitoring people who enter. As pointed out by Al Teich, Director of Science and Policy Programs for the American Association for the Advancement of Science, “revolving doors can be outfitted with biometric devices, metal detectors, and other screening and access control mechanisms.” These mechanisms can prove invaluable in the modern world.

Revolving doors have come a long way from their humble beginnings in Philadelphia. They have become a staple of skyscrapers and smaller buildings worldwide, for both their efficiency and aesthetics. The doors have kept crowds moving and even comically entertained for decades. Best of all, though, they have kept the noise down and the cold out, just as Theophilus Van Kannel had intended.

The Center would like to thank the National Inventors Hall of Fame and Dr. Don Potter of the University of Georgia for their assistance in illustrating this article.

Sources:

- Buzard, James. “Modernism/Modernity.” Perpetual Revolution. 8.4 (2001): 559-81.

- Grimes, William. Appetite City: A Culinary History of New York. New York, NY: North Point Press, 2009. 136.

- Henderson, Tessa.”Revolving Doors Harvest Human Energy - Energy Harvesting Journal.” Energy Harvesting Journal by IDTechEx. 15 October 2010. <http://www.energyharvestingjournal.com/articles/revolving-doors-harvest-human-energy-00001686.asp>.

- “International Revolving Door Products, 3D CAD, Specs, Catalogs Sweets.” Building Materials, Products, Manufacturers - Sweets Network -- Find Construction Materials and Tools for Architects. 15 October 2010. <http://products.construction.com/Manufacturer/International-Revolving-Door-NST784/overview>.

- Mocine-McQueen, Marcos. “Circular Logic; Sure, They’re Fun, but Revolving Doors Also Have a Higher Purpose - New York Times.” The New York Times. 27 July 2002. 3 November 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/27/nyregion/circular-logic-sure-they-re-fun-but-revolving-doors-also-have-a-higher-purpose.html>.

- “Revolving Doors: Sustainability at MIT.” Sustainability at MIT: Infinite Possibilities - Finite World. 14 October 2010. <http://sustainability.mit.edu/content/revolving-doors>.

- Teich, Al. “Revolving Doors—Always Open, Always Closed.” Teich’s Tidbit. February 2003. <http://www.alteich.com/tidbits/t020303.htm>.