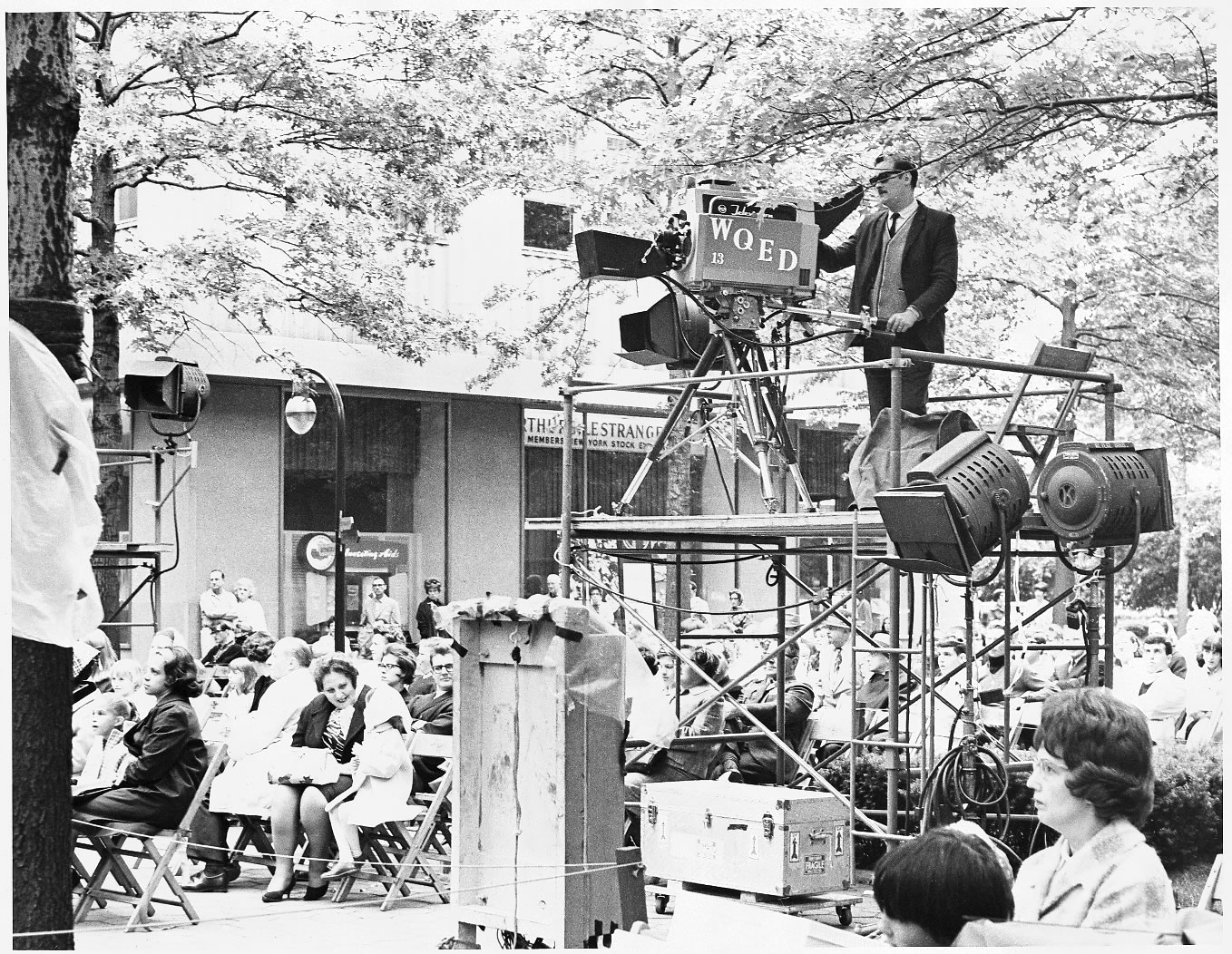

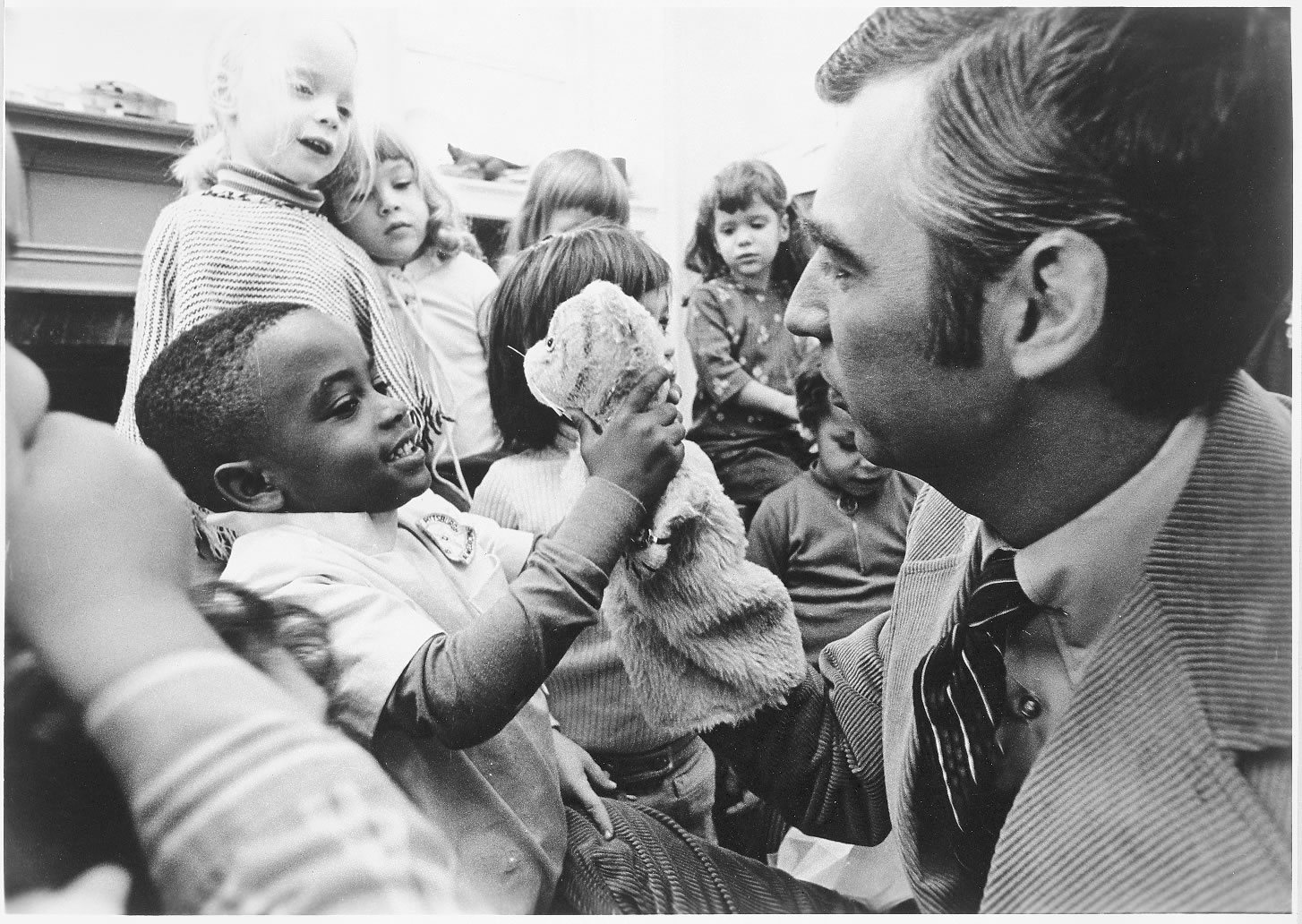

It’s a beautiful day in this neighborhood, a beautiful day for a neighbor, would you be mine? Could you be mine?” It’s February 1968, and Fred Rogers is singing the now world famous intro song to his children’s television show, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. For the first time, Rogers is slipping off his dress shoes and sliding on a cardigan in front of a nation-wide audience; PBS has just begun nationally broadcasting the show. The origin of the broadcast is Public Broadcasting Station WQED in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. WQED was the first community-sponsored television station in the United States and since 1954, has been a pioneer in children’s and educational programming. Throughout its fifty-plus years of history, WQED has produced high-quality programming seen not only by citizens of Pittsburgh, but also by PBS viewers across the nation.

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood is just one example of many successful programs produced by WQED. Today the list includes a variety of programs including National Geographic Specials, the Wonderworks series and the Pittsburgh History series. Successful programming has led to hundreds of excellence awards on local, regional and national levels. However, a close look at WQED’s history reveals a story of the difficulties in bringing educational programming to television, and the station’s struggle to remain economically viable in an increasingly competitive media industry.

The story of WQED begins in January 1953 when the station was first incorporated under the name of Metropolitan Pittsburgh Educational Television. David L. Lawrence, the then mayor of Pittsburgh, was the driving force behind the idea and creation of a public television station for Pittsburgh. Lawrence was a large proponent of non-commercial television and campaigned to have twelve percent of all television stations reserved for educational use. At the time, broadcast television licenses from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) were in high demand and a freeze had been placed on the issuance of new licenses. Furthermore, Westinghouse Electric, owner of popular Pittsburgh radio station KDKA, was also in the market to secure a television license for the creation of KDKA-TV. However, Mayor Lawrence had close ties to the Democratic Party and then President Harry Truman, who assisted him in convincing the FCC to grant the city of Pittsburgh a license under the stipulation that they produce the necessary funds to support a station.

Westinghouse was not quick to let up in its fight though, and the company lobbied for the FCC to grant the license to KDKA and allow it to be shared with a community station. Leland Hazard, a colleague of Mayor Lawrence and the eventual first president of WQED, managed to convince Westinghouse not to pursue their interests. Eventually the electric company would become one of WQED’s earliest partners and supporters by donating to WQED, the broadcast tower KDKA had planned to use for its television station. Hazard’s place of employment, the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company, would also donate WQED’s first studio space at the corner of Fifth and Bellefield Avenues in downtown Pittsburgh. With a license, broadcast tower, and studio secured, WQED had taken its first steps towards bringing educational programming to the Pittsburgh area.

Before the station could begin delivering content, the appropriate finances were needed, and thus WQED’s focus quickly turned to fundraising. One of the most memorable fundraising practices for the station was sending groups of school children door-to-door to solicit homeowners for a $2 annual donation. More than 60,000 Pittsburgh citizens would pledge their support to these children. Josie Carey, one of the earliest employees at WQED, remembers this fundraising tactic. “We went door to door collecting two dollars per family,” she says. “We collected money from the schools for in-school programming. We never intended to be the equal of networks; we were a community station.”

This door-to-door fundraising, combined with large donations from trusts and funds such as the Ford Foundation and the A.W. Mellon trust, allowed WQED to begin broadcasting on April 1, 1954. The station is the fifth public broadcasting station in the nation, the third educational-based station, and the country’s first community-supported station. One Pittsburgh Press columnist wrote that the station “could, conceivably, have as great an impact upon civilization as the first free public school.”

The call letters of WQED are based on the latin phrase “Quod Erat Demonstradum,” which translates to “let it be demonstrated.” Let it be demonstrated, perhaps, that a small group of individuals dedicated to furthering education were able to begin making a difference in their local communities.

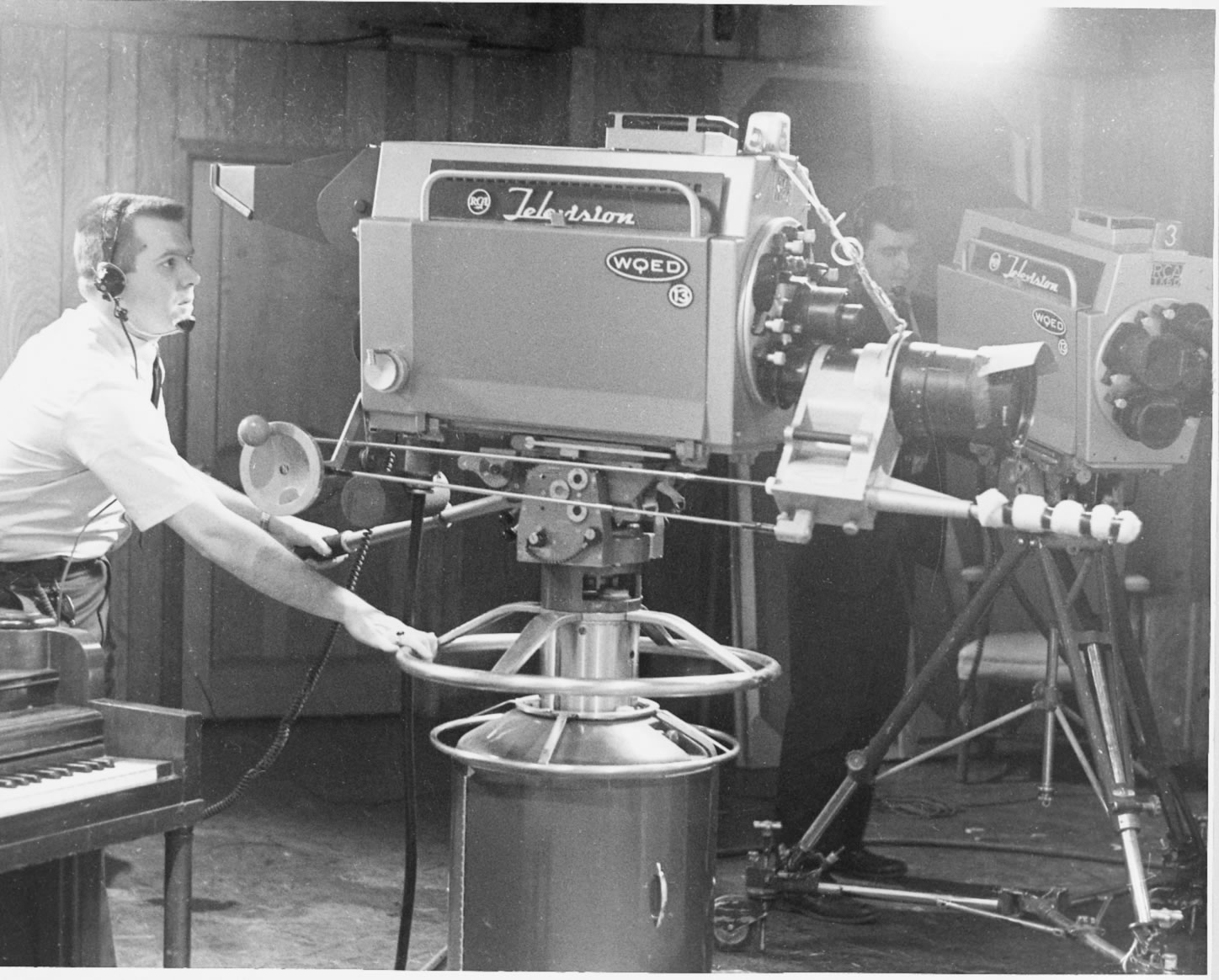

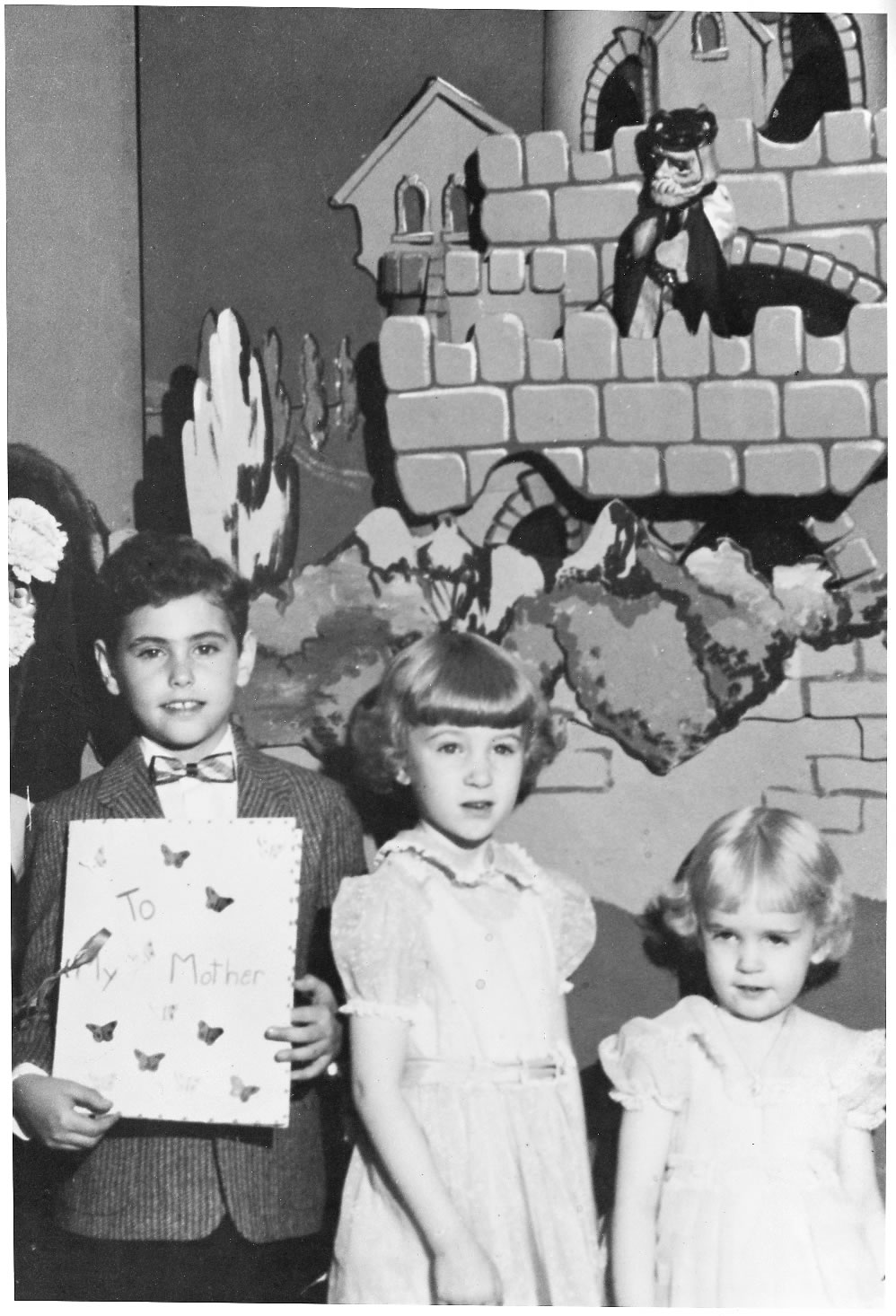

One of the first successful shows on WQED was The Children’s Corner, hosted by the aforementioned Josie Carey, and produced by the rising star Fred Rogers. The show aired daily at 5pm, and aimed to fill the gap in children’s lives between the end of school day and suppertime. The show gave birth to many of the puppets and characters that would eventually be the stars of Mister Rogers Neighborhood. In addition to being the producer, Rogers played the role of puppeteer, composer, and organist. “Nobody really knew what they were doing,” says Carey. “We had a very long room for the studio with the organ at one end and the set at the other. Fred would have to run down to play the organ, then run back up to the set.” Despite the impractical layout of the studio, the show brought WQED one of its first awards: the 1955 Sylvania Award for Best Locally Produced Children’s Television Program in the Nation.

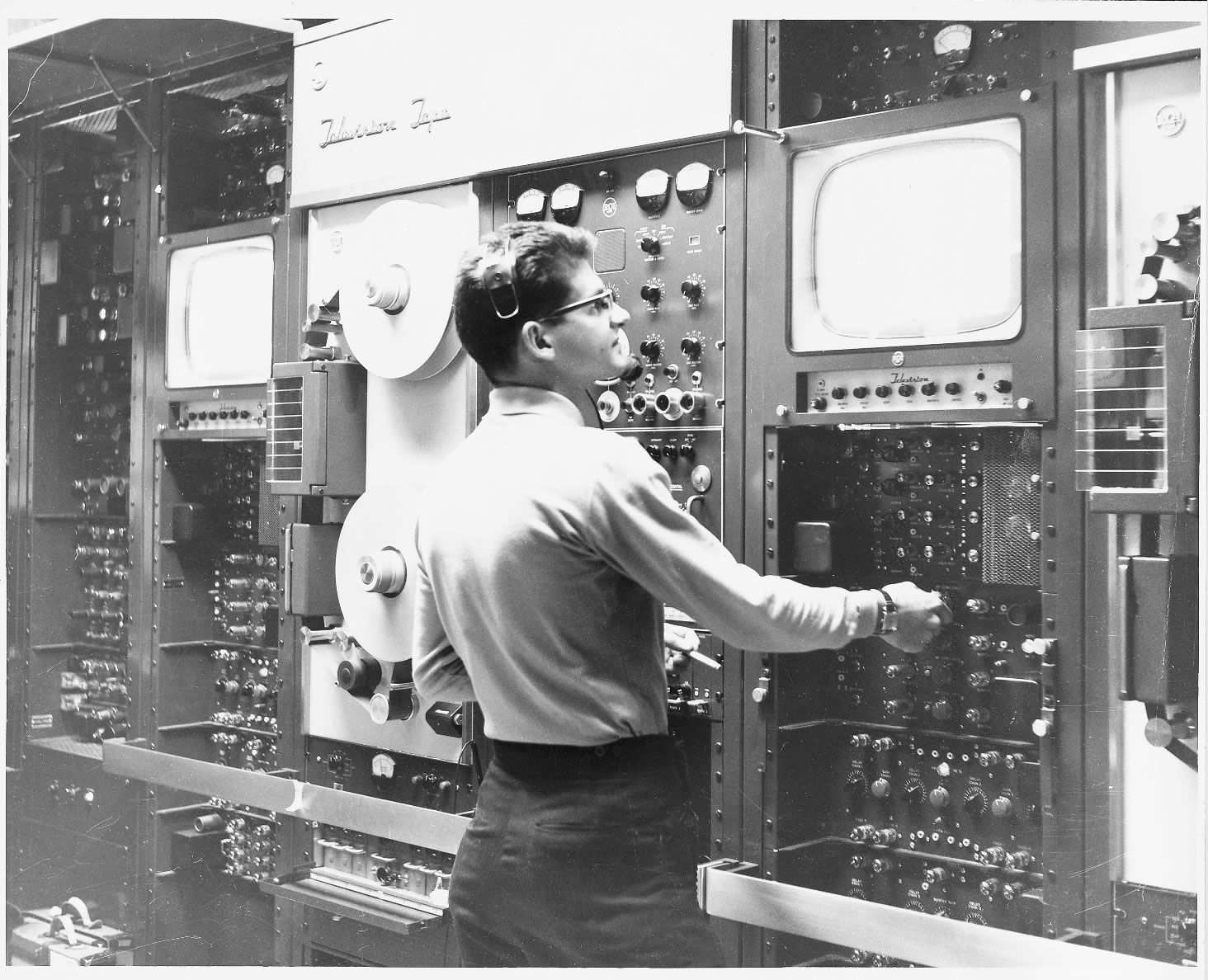

Carey would eventually leave the station, leaving the door open for Rogers to transition the “corner” into the “neighborhood.” At the same time, WQED’s attempts to bring educational programming to local classrooms were just beginning to take off. In 1955, 13 Allegheny Area schools were part of the first televised school lessons ever. In 1959, a second, strictly educational station is added to the WQED lineup: WQEX. By 1964, more than 500,000 Pittsburgh area students were receiving televised lessons through the two channels.

The 1970s were defined by significant growth in multiple areas for WQED. The beginning of the decade brought a new home to the station on Fifth Avenue in Pittsburgh, where it remains today. More than 8,000 people showed up at the station on the day it opened, hoping to get a tour of the new facility. Shortly after the opening of the new building, WQED announced the acquisition of the magazine Renaissance, which would eventually become Pittsburgh Magazine. The year 1973 saw the creation of WQED’s first radio station, WQED-FM 89.3. The station is focused strictly on classical music, and became a critical outlet for local artists. Today, WQED-FM records over 100 local concerts a year for re-broadcast on the station.

The success of the station continued well into the 1980s. WQED’s funding expanded to the point where many local and national corporations were spending millions of dollars to support certain shows. Gulf Oil would donate millions of dollars in advance to support the National Geographic Specials, which helped WQED become the fourth-biggest supplier of national programming to PBS. While the station’s worth was reaching an all time high, it also seemed to be pulling away from WQED’s roots in community-focused fundraising and programming. While a $2 annual donation from Pittsburgh households would no longer support the station, the duty of the station, and the broadcast license, now focused more on national programming than serving and educating the citizens of Pittsburgh.

By 1990, only 60 hours of local programming was being broadcast yearly on WQED. The national average for public broadcasting stations at the time was 105 hours yearly. When station president at the time Lloyd Kaiser was questioned about the significant decline in Pittsburgh-centric programming, he stated that local programming is a “poor investment and should be avoided to place more resources into purchasing national programming.”

In 1993, shortly after that statement, Kaiser was forced into retirement after the station posted a yearly loss of $7.4 million. More than 25 percent of the staff was laid off as well. Because of the recession, the national programming that had kept WQED growing for years was no longer a viable source of income, but the station’s executives refused to take the necessary actions to steer the station out of trouble. Ron Bencke, Chief Financial Officer, says “We thought national programming would come back and this was temporary. We got used to the old lifestyle.”

The problems for WQED did not end with financial difficulties. After Kaiser’s retirement it was uncovered that top executives had been raking in outrageous benefits for years, receiving private gifts and adjusting their salaries without informing the board. Trust between WQED and the Pittsburgh community was at an all-time low, and WQED seemed to be drowning in a changing media landscape. The cable television industry was booming, and newer, more popular commercial stations continually threatened WQED’s livelihood. The station was in need of a new focus, a renewed connection to the community, and a dedicated leader. George Miles would be appointed to the position of station president in 1994, a position that he still holds today. Over the past 15 years, Miles has managed to draw WQED out of its troubles of the early 1990s and ties with the Pittsburgh community are stronger than ever today. Local programming is again at the focus of WQED, and Miles says he now think of WQED as a “great local, local resource.”

While today WQED may not be producing the national programming that it once did, it is still setting standards nationally for the role a public and educational station should play within a community. Pittsburgh citizens see the station as a symbol of pride, which accurately represents the culture and values of the steel town. Local programming continues to preserve the culture of Pittsburgh through its expansive history series, and WQED-FM takes Pittsburgh national with weekly national broadcasts of the Pittsburgh Symphony. With nearly half of their programming being focused on children, WQED also continues to be a national leader in educational content.

WQED producer T.J. Lubinsky says, “most Pittsburghers think of us a very large church. We’re all in this together. We rely on everybody else to give us support so we can keep on doing this.” It was this type of mindset that brought WQED to life in 1954, when thousands of supporters donated a few dollars to start the nation’s first community-sponsored television station. 56 years later, WQED remains true to its values, providing outstanding educational programming to the Pittsburgh area, the nation, and the world.

Sources:

- Hoover, Bob, Sally Kalson, and Barbara Vancheri. “WQED at 50: Born in television’s golden Age, Pittsburgh’s public broadcasting station pioneered educational programming.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 28 Mar. 2004. 4 Mar. 2010. <http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/04088/291370.stm>.

- Levin, Robert A., and Laurie M. Hines. “Educational Television, Fred Rogers, and the History of Education.” History of Education Quarterly 43.2 (2003): 262-75.

- Owen, Robert. “Broadcast pioneer Josie Carey was there from the start.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 28 Mar. 2004. 4 Mar. 2010. <http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/04088/291310.stm>.

- Starr, Jerold M. Air Wars; The Fight to Reclaim Public Broadcasting. Boston: Beacon Press, 2000. 1-8.

- Togyer, Jason. “Creating ‘QED . at DuMont’s expense?.” Pittsburgh Radio & TV Online. Ed. Eric O’Brien. N.p., 4 May 2009. 4 Mar. 2010. <http://pbrtv.com/blog/entry_1003.php>.

- Vancheri, Barbara. “WQED at 50: A Timeline.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 28 Mar. 2004. 4 Mar. 2010. <http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/04088/292026.stm>.

- “WQED Multimedia: About Us.” WQED Changes Lives. 5 Mar. 2010. <http://www.wqed.org/about/history.php>.

GALLERY